We all have so much freedom to bring whatever we want to the dance, which is why dancing is powerful.

~ Louise Siddons

Louise was born in the UK but moved to the United States as a child, where she grew up surrounded by folk music and song. She began folk dancing seriously in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 2008, and started calling soon after. Now back in the UK permanently, she is known on both sides of the Atlantic as a contra, English country dance, and ceilidh caller.

Louise believes that we should invest in the evolution and sustainability of folk traditions and their ongoing relevance to contemporary culture—whether that’s through gender-free calling or adapting dances for Zoom. As a caller and dance teacher, she strives to create a fun and welcoming atmosphere with her low-key and lighthearted stage presence. At its best, social folk dance is a living tradition that balances accessibility with challenge and discovery. Louise calls a mixture of modern and historic dances in a variety of formations, and enjoys helping dancers discover the musicality of choreography, from the familiar to the unexpected.

In their conversation Mary and Louise trace her involvement with communities in Michigan and Oklahoma, and across the pond in the UK. We’ll also learn about her work developing and teaching the practice of “positional calling” for social dance, which has recently culminated in a new book, published through CDSS, called Dancing the Whole Dance: Positional Calling for Contra. In the interview Louise shares what it’s been like to step into a leading role in the discussion about positional calling, and how her personal experiences on and off the dance floor have shaped her approach to dance leadership.

Show Notes

Sound bites featured in this episode (in order of appearance):

-

Louise calling the dance The Reminder by Louise Siddons at the London Barndance in London, UK with music by Portland Drive.

-

Louise calling the square dance Square Line Special by Gary Roodman at the Brighton Gender-Free Contra+ dance in Brighton, UK with fiddling by Linda Game.

More about Louise

- You can buy Louise’s book, Dancing the Whole Dance: Positional Calling for Contra here!

- Louise has offered a number of online workshops related to positional calling, which are accessible here on her website (along with lots of other goodies!)

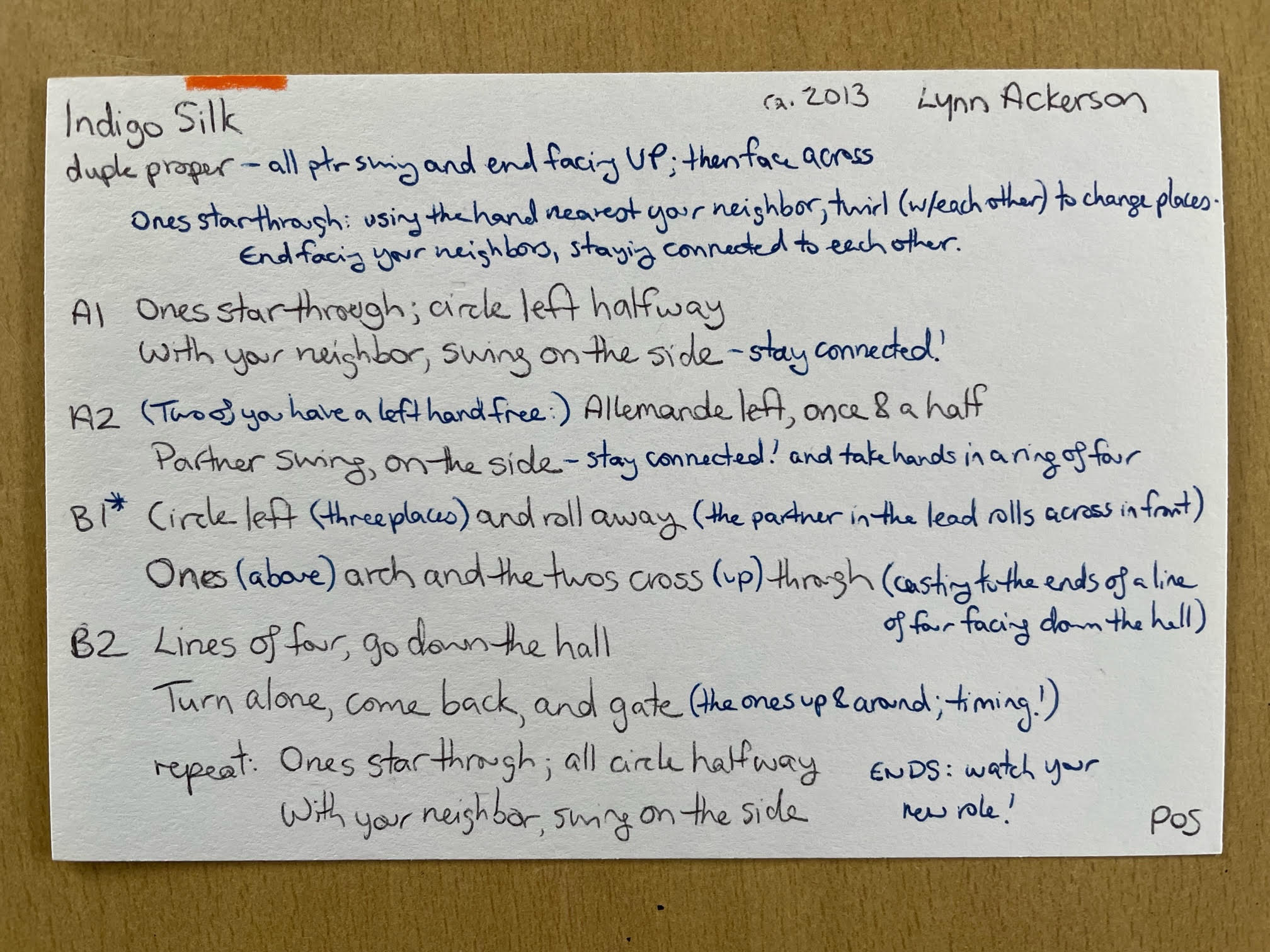

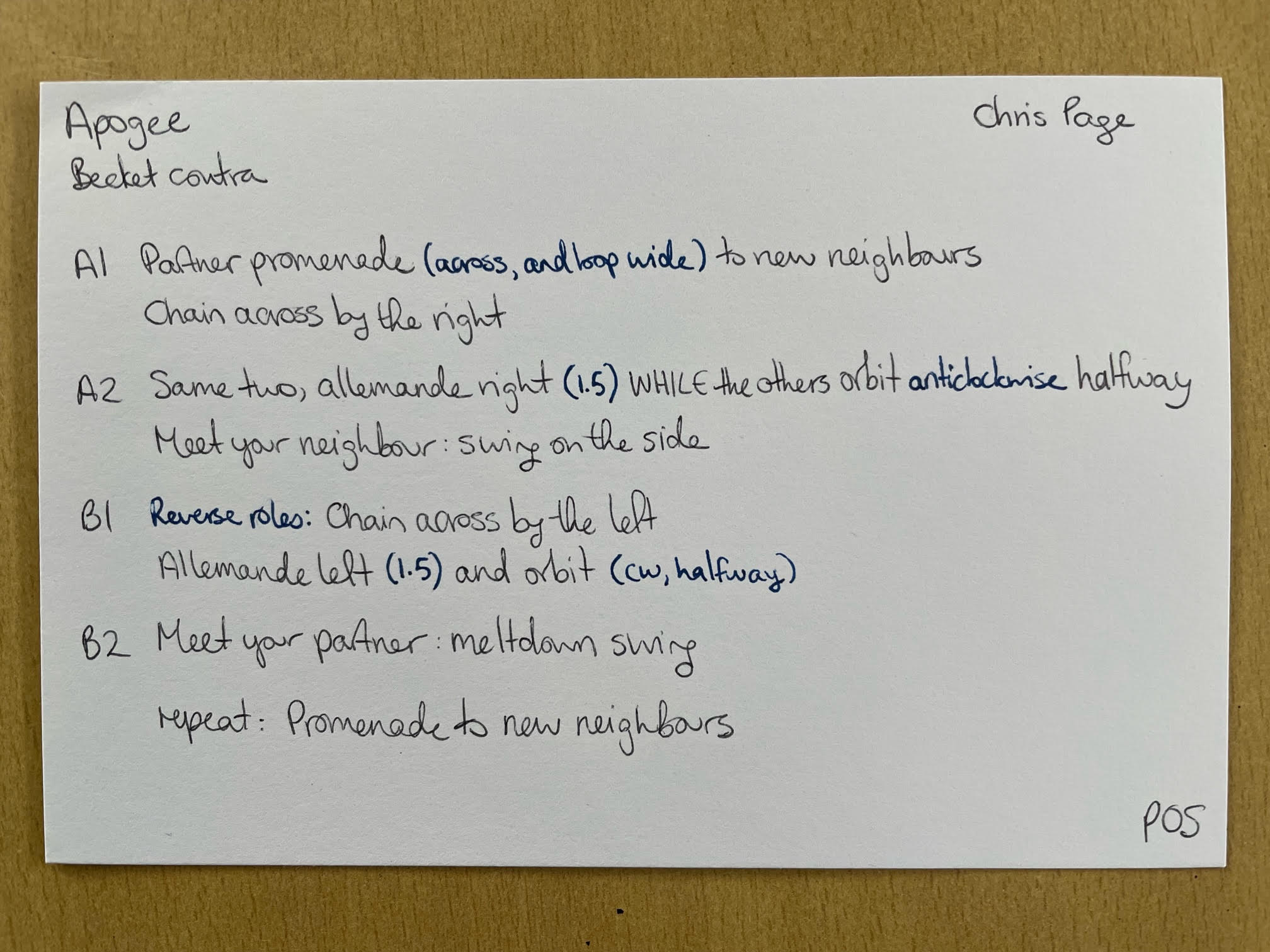

Dance Notation

Examples of Louise’s dane cards!

Episode Transcript

Click here to download a transcript.

Ben Williams This podcast is produced by CDSS, the Country Dance and Song Society. CDSS provides programs and resources, like this podcast, that support people in building and sustaining vibrant communities through participatory dance, music, and song. Want to support this podcast and our other work? Visit cdss.org to donate or become a member today.

Mary Hey there – I’m Mary Wesley and this is From the Mic – a podcast about North American social dance calling.

Louise Intro

Mary Hi From the Mic listeners, it’s me Mary back with another caller conversation for you. This time we’re headed overseas to the UK to chat with Louise Siddons.

Louise was born in the UK but moved to the United States as a child, where she grew up surrounded by folk music and song. She began folk dancing seriously in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 2008, and started calling soon after. Now back in the UK permanently, she is known on both sides of the Atlantic as a contra, English country dance, and ceilidh caller.

Louise believes that we should invest in the evolution and sustainability of folk traditions and their ongoing relevance to contemporary culture—whether that’s through gender-free calling or adapting dances for Zoom. As a caller and dance teacher, she strives to create a fun and welcoming atmosphere with her low-key and lighthearted stage presence. At its best, social folk dance is a living tradition that balances accessibility with challenge and discovery. Louise calls a mixture of modern and historic dances in a variety of formations, and enjoys helping dancers discover the musicality of choreography, from the familiar to the unexpected.

We covered a lot of ground in our conversation, tracing Louise’s involvement with communities in Michigan and Oklahoma, and across the pond in the UK. I was also excited to learn about her work developing and teaching the practice of “positional calling” for social dance, which has recently culminated in a new book, published through CDSS, called Dancing the Whole Dance: Positional Calling for Contra. In the interview Louise shares what it’s been like to step into a leading role in the discussion about positional calling, and how her personal experiences on and off the dance floor have shaped her approach to dance leadership.

Mary Hello, Louise! Welcome to From the Mic.

Louise Hello Mary, thank you for having me. It’s lovely to be here.

Mary I’m so glad to see you. Where are you speaking to us from today?

Louise So I am speaking to you from my sitting room, which is in Winchester, which is in Hampshire, in the U.K.

Mary Beautiful. What brought you there?

Louise Well, it’s sort of a long story. I’m from here in the sense that I was born in London and we emigrated when I was about five and then I lived all over the States for a very long time. I’m an academic. I’m an art historian by training. So I came back here in January of 2021 on a Fulbright Fellowship and had been coming back every summer for 20 odd years, staying with family, things like that, and have always loved England. In some ways always missed it, although I think that’s a bit of a misnomer because I don’t remember huge amounts from when I was little. But in any case, I was here for six months. About three months in I realized I didn’t want to leave. So I started plotting how to stay and now I work at the Winchester School of Art. I’m a professor of visual politics and head of the Department of Art and Media Technology.

Mary Wonderful. Wow. I didn’t know that you had family connections in the area as well. That’s great. So where in that trajectory did you encounter social dancing?

Louise I started social dancing in California, technically. I started doing historic ballroom dance. I went to the Dickens Fair, which is this event in the Cow Palace in San Francisco with friends. I was not enthusiastic about it. I had a certain level of skepticism, I think would be the safe word about an event where a bunch of people pretended to be in Dickensian London.

Mary Did you wear a costume?

Louise Yeah, exactly. But they have a dance floor and we were sort of hanging around watching the dance floor and my mother had taught me to waltz when I was tiny. Like a box step waltz. They have staff who have to ask the regular patrons to dance and someone asked me to dance and I was like, “Oh, yeah, I know how to waltz!” And of course they’re doing a rotary waltz. Not a box step in any form and I am determinedly trying to box step at this poor man who is trying to waltz with me. In the unlikely event, I actually fell in love with the dancing and so there was that and then I also had started doing swing dancing lessons and started with a friend who very quickly hated it. But I loved it so I kept going. So I was doing kind of really ballroom style social dance at first, and then got a job in Michigan at Michigan State and moved to Michigan in 2007. I couldn’t really find any ballroom to do, especially that wasn’t very student oriented, which felt a little uncomfortable as faculty. So a colleague of mine, Julie Levy Weston, is a contra dance caller in Lansing, and she also worked at the Michigan State Museum. So she would put out on the public humanities listserv: contra dance in Lansing! It’s free your first time! So I think January 2008 dance was my first contra dance ever. And again, just was like, what is this magic? I need to do more of this. I immediately found the English country dance in Ann Arbor and started going to that. I did all the dancing I could find, drove up and down Michigan for the two years that I lived there, dancing everywhere that I could multiple times a week and that’s where I started calling as well.

Learning to call

Mary Nice, nice. Can you go into a little more detail about how you started calling? What got you from the dance floor to the mic?

Louise So I went to this contra dance and then just wanted to find every other folk dance type thing I could. And someone said, “Oh you must go to Ann Arbor and try English dancing,” because there is now English country dancing in Lansing, but there wasn’t at the time, Ann Arbor was the closest. So I went and I was the only new dancer there, and it was run by Ray Bantle. And he does a very welcoming, sort of informal introduction if new people come. So there I was very obviously new, slightly nervous, and he took me under his wing and sort of taught me how to do a setting step and sort of said, “You’ll figure it out from there.” Probably introduced the concept of progression, but having been to a contra dance, I was fully prepared for that event. Then about three months later he’s like: “Your sense of timing is impeccable and you’re a very fast learner. You should be a caller.” So three or four of us ended up doing a series of workshops. I found us a classroom at Michigan State that we could use to practice and started calling. So it was English that I started with. Then just before I left Michigan, I was there for two years and then I got a job in Oklahoma. And just before I left, I think literally the last dance event that I was at, Ed Vincent, who’s a contra dance caller, also in Michigan, I think from Ann Arbor. He was like: “Well, if you can call English, you should call contra. I’m not going to let you leave Michigan without calling contra.” So he taught me the dance Midwest Folklore by Orace Johnson and I just sat on the floor in his living room with a recording and him kind of being like, “Just call! Just call to me.” So I left Michigan, having called one contra dance to one human being.

Mary You’ve got to start somewhere.

Louise Exactly, exactly. And so then I moved to Oklahoma and sort of rocked up at their English dance, being like, “Hi, I’m a caller, I want to call.” And yeah, it was like, “Well, that’s great, you can call English. But actually what we really need is a contra dance caller because one of our callers is moving away.” So yeah, didn’t have to, but sort of embraced the challenge, if you will. The lovely, lovely dancers of Oklahoma City were very patient with me as I learned sort of on them, to call contra dances as well. I found it really challenging in comparison with English because the music is structured the same basically for every dance, right? I was used to the music, kind of reminding me how the dance went. I’m not one of those people who will say the music tells you what to do, but if you’ve practiced the dance a whole lot before you stand up there and call it, then when you hear the tune, it does in fact tell you what to do, which with contra, that wasn’t the case. So at first, because I’m not particularly a musician, it was like I was losing track of the A’s and the B’s and it was like really kind of a different skill to have to learn. I think, in fact, contra dance made me much more musically aware than English country dance calling ever did.

Mary Yeah, that’s so interesting. I’ve never thought of that comparison. And like, for me, I just came into contra dance and mostly stayed there. I call contra and squares and that’s always been what intimidates me about English calling is the variety of tunes and meters and things like that whereas contra dancing is very formulaic in that way. Your AA/BB structure is pretty much it for the most part. But when I dance English, that is what I love, that variety and I can see doing it enough times that you have that stronger association with the music and the movement and that’s what I love about chestnuts too. You know, that’s kind of all we have in contra dance land that kind of echoes that experience of like you hear Chorus Jig and you’re going to be going down the outside, like that’s where you’re going to go.

Louise Yeah, yeah, exactly that. I love chestnuts for the same reason. I think they’re a nice crossover, too. Also, they’re this opportunity to realize that English dancing can be as energetic and lively and sort of the music can be just as transcendent as contra. I think that a lot of people might say that you don’t get into the same flow state with English dancing as you do with contra and I think it’s harder to achieve, maybe. But, you know, moving here, it’s been fascinating because a lot of dancers here, especially in the English Ceilidh scene, they still do a lot of what I think of as kind of chestnuty, English dances. By which I probably mostly mean first edition Playford. I never understood why those dances had any appeal until I saw a bunch of Ceilidh dancers do them and I’m like, oh my gosh, right, this is Money Musk. This is Money Musk for this community. And yeah, I could find that same joy suddenly in it.

Mary Nice. So it sounds like you had such a nice thing, which is when someone recognizes you and invites you sort of into something. I think that can be such a sign of encouragement in addition to those community folks who kind of stepped up and said, “Hey, come in, come try this!” Like what pulled you into it? Were you already a teacher? You know, I’m curious about that connection.

Louise I think it’s a bunch of different things like for months probably, I can’t really remember, but for a long time I would go to a contra dance and I would bring a book with me and it would be like I am dancing and then in the break I am reading my book because I’m just waiting for the 15 or 20 minutes until we’re dancing again. So my social skills are sort of on the extreme introvert side, I think. It just took me a long time to realize that people thought of themselves as a community, which I think also to a certain extent comes from the fact that I just move around a lot and so that sense of community was sort of precarious for me. It was built around kind of shared purpose, rather than just ‘all happening to be in the same place’ kind of communities. Dancing gives you that sense of shared purpose. But I think also calling gives you and other people that you’ve interviewed who said this, right, like calling gives you the purpose in the room beyond just like, I’m dancing. For me, because I grew up in a family of musicians but wasn’t a musician myself, it also gave me like, oh, this is how I have a purpose kind of in the world of music. Dance was not something that I grew up with necessarily, and so it was important to have that way to have conversations with my family that I couldn’t have before. That was a sort of upside to it. But I think definitely the fact that I was a teacher already helped and I had discovered…I went to grad school to do my Ph.D. because I wanted to be a curator, which is also this very kind of introverted way to be an academic, right? Like, I want to find my art museum and I want to hide in the back with all this stuff and my interaction with the public will be through exhibitions, not through direct contact. And obviously, I mean, people who work at museums know that there’s a lot of public facing stuff that you do, but it is this fundamentally kind of hidden away sort of task. I discovered, because I had to teach for my grad fellowship, that I enjoyed teaching and that I was good at teaching, which I hadn’t expected. I think the way in which I enjoyed teaching was…I mean, I was lucky to have some brilliant, brilliant teachers to watch. And so as I was thinking really for the first time, like, “Oh my goodness, I need to develop this skill.” I was watching what they did and aspiring to kind of do similar things. One of those things is guiding a conversation. Getting people to get somewhere themselves instead of just telling them where to go, and that’s such an obvious parallel to doing a walk through, right? Like, I don’t want to just tell you where to go, I want you to understand why you’re going there and how you got there so that I don’t have to tell you again nine times.

Mary Yeah. That makes so much sense.

Louise So it’s this distillation of one of the most fun things about teaching for me.

Mary I love that and then adding on this sort of 3D, physical, like, embodied layer to all of that.

Louise Yeah, exactly. I mean, this is true for art history too, I’m so grateful that by whatever fluke of circumstance I ended up being an art historian instead of a literature scholar or something like that, because no one takes an art history class who doesn’t want to be there. Like you really have to seek it out, whereas everyone has to take freshman composition. So my whole teaching career, I’ve been teaching people who have self-selected to be present, and a contra dance is that too. Even the people who are nervous and who are unsure, chose to be there. So you can just go in and be like, I am sort of wholeheartedly trying to make you happy about the decision you made to show up in this place. And that gives me the freedom, I think, to just be kind of unabashedly passionate about what we’re doing together and that’s really lovely.

Mary So how did things develop once you started calling in Oklahoma?

Louise So pretty straightforwardly, probably. I called a lot. I was really terrible at first and I got better. I think that one of the hardest things for me is not losing my temper. So it was like a lot of life lessons for me wrapped up in also just learning the technical kind of skills of calling.

Mary Like losing your temper when things aren’t going as you want them to?

Louise Like in every way. I remember the absolute nadir of my calling career was, I was trying to teach something, lots of people in the hall were chatting, I couldn’t hear anything, it was a really live hall. It was like a nightmare to do sound and the band was talking, the people on the dance floor were talking, there were some confused people. And I just said, “Shut up.”

Mary Which we’ve all thought in our heads a million times!

Louise Yeah, but that’s not supposed to come out of your mouth over the mic. To be fair to everyone in the room, they were very nice about it. A couple of people came up to me afterwards and were like, “You know, it would really be better if you didn’t say things like that over the mic.” I was like “Yes, it would, we all agree on this point.” I just feel really lucky that at that point I had learned this lesson about community and I had a huge amount of respect for them, for trusting. I was one of a bunch of new callers that were all doing workshops and learning together, and that the dancers trusted us and they wanted to help us learn and so they were really generous about it. But yeah, things like that and so I think there’s a lot of kind of learning to be a little bit calm and zen. I had a moment just last autumn…I can’t remember what the circumstances were, but there I was at a dance, it was on the level of like the hall was full of chairs and tables and the band wasn’t there and obviously nothing was ready for this dance to happen in about 20 minutes. I was just like, you know, I could be really kind of upset about this, or I could just be like, ehh, at some point people will show up, we’ll move some chairs, we’ll have a dance, it’s fine. And I was like, “Oh, Louise look, you have learned a thing!”

Mary Beautiful!

Louise So I think it’s a journey. But I definitely think it’s part of being new at something, right? It’s like you’re anxious and your anxiety is sort of on behalf of the people who you know you might fail. And the lesson is like, “No one cares.” Joseph Pimentel does this hilarious thing, he makes a mistake and he plucks it out of the air, literally physically, and then throws it away.

Mary I love that.

Louise And I think of him every time now and I’m just like, what a brilliant thing. Because he also is like, “I am too much of a perfectionist and I need to move past that.” I’m like, “Yes, that resonates with me hugely.” I feel like the master moment is like, I don’t even need to pluck it out of the air anymore, it left of its own accord.

Mary Yes, it just dissolved…Yeah I feel like that’s something we don’t talk about a lot because it is kind of the role. It’s both kind of just the social role of the leader or the caller is that you’re projecting confidence and having the situation in hand while all kinds of things might be going on under under the cover of that…which, like you said happens in many different life situations. But it is really cool to think of that as one of the things…the arcs of learning to be a caller too, is how to integrate all of that. And then in addition to just the skills of what are the moves and what is the timing. It’s…how are you holding this room full of people? Which really entails you being really profoundly affected by everything that is around you because you’re really trying to hold it. Like, as I’m saying this, I’m like holding my arms out because I experience it too as like such a visceral thing. I feel a slight physical connection to every body in the room. Or somebody like putting a fan in the window because it got hot. Like all this stuff that’s happening at the same time, you’re getting this sort of feedback and it’s a lot to manage while then trying to like sort of say words over the microphone.

Louise I think it’s a funny thing too, because it’s that sense of like responsibility and caretaking. And so for me, in that moment, it was like, I am trying to help people who need my help. It’s this frustration that comes of like an excess of…I don’t know what, like well-meaning-ness that just goes horribly awry somehow. I think it was also maybe the lesson of like it’s a team. I say all the time now, it’s a team sport; we are all there teaching each other and learning together. And in fact, like I need to learn, like if people are being really chatty, it’s because they need to chat in that moment.

Mary Right. It’s also social dance, and they’re socializing.

Louise Which I think, you know, based on I took a book and didn’t socialize. It was actually a thing I had to consciously remind myself of early on is like, yeah, people are here to talk to each other. I remember the Tulsa contra dance when I first started dancing there, it was like they would dance for 5 minutes and break for ten and dance for five. And I was like, “What is this phenomenon?” But it was a group of people who just really enjoyed each other’s company, and they were like, “We’re choosing to spend 3 hours of our time together. Here’s how we want to spend it.” It was what it was, it was really not intentional, but it had formed out of the needs of the people there.

Formative dance communities

Mary Yeah. You know, having kind of lived in a couple of different places and been in some different communities, what have you noticed about the different places you’ve been? Are there kind of regional styles or…

Louise It’s interesting, I think, it’s not so much region as size of community. I’m not sure I can count accurately, but Michigan was networked enough that there were, say, a dozen contra dance callers who were Michiganders, but also people came through all the time and so you had a lot of variety of callers and that sort of reseeded the community in various ways. It brought in new dances that then got collected by local callers. It brought in bands all the time so you heard different styles of music. Whereas in Oklahoma we had four cities ultimately by the time I moved away that had dances in them. But we also only had about four callers and we only had about four bands and so people heard the same things all the time. When I moved to Oklahoma, my perspective, as a relatively new contra dancer, but one who’d already been to Pinewoods and kind of had been traveling all over the country dancing, because any time I went somewhere for work, which I did a lot of, I would dance, right? So I had this kind of cosmopolitan understanding of what contra dancing was and went into a community where people didn’t really travel as much and the callers had been calling there for decades. It was kind of a snapshot in time, in a way, of what contra dancing was in like, the eighties, even though it was 2009 by the time I moved there. And that’s not entirely true. Obviously people traveled and they collected dances and things, but there was still kind of a diversity of choreography that I think had disappeared certainly from the coasts and was disappearing in Michigan. When I started dancing in Michigan, there were two square dances in every set at every contra dance. I mean two in a row as one does.

And by the time I was calling contra well enough to be traveling, I was being told, “Do not call squares.” And even in Michigan, getting that feedback, so that narrowing, I think really impacted my experience of how dancing was changing more than maybe regions did. I appreciated the fact that Oklahoma dancers were willing to try things that if I was on a coast I would have gotten sort of booed for calling.

Mary Yeah, I definitely experienced that when I was there this winter, it seemed fine that I threw in a couple squares, we even did a triplet, we did some chestnuts. Also, it was a weekend so you have kind of more space to do that. It sounds like you got involved in lots of different facets of dancing in Oklahoma.

Louise Yeah, so I was calling and then the woman who was running the caller workshops left. So I kind of took that over at some point, joined the board, it is a statewide organization that runs the dances in Oklahoma, so I joined that board. Because I was teaching at Oklahoma State, the students there, we sort of had this moment where we realized there were multiple Stillwater people driving to Oklahoma City for the contra dance and one of the students said, “Why don’t we start a dance here?” And I said, “If you find the dancers, I’m happy to call.” It was early enough that I was like, I need the practice. So I became the student advisor for the student club, called for free for years and years and years until we got going. And they did, they had a really healthy dance and it was that dance that first went gender free in Oklahoma, they were a great group. And then we started a little Irish set group because I was sick of coming to the UK for two months dancing Irish sets and then going back to Oklahoma where there were none. So I think to a certain extent it was like, yeah, it’s the kind of dance community where you can come into it and say, “Here’s what I would like to do, will you all do it with me?” So Irish sets was like a natural addition in a way, even though it wasn’t part of the organization officially. There was a lot of freedom to do whatever we wanted.

Mary Nice. I think a lot of callers step into organizer roles in different ways. Like in that example, it sounds like you’re sort of already connected with your school community and an obvious person for students to kind of approach. Did that come naturally and did you feel excited to sort of be part of shaping other opportunities for dance to happen?

Louise Do I want to say it’s part of a natural kind of progression of sort of leadership? It might not be.

Mary That’s a good question, I never thought about it.

Louise I think my sort of model of being in the world is that you join a thing and then you take on some responsibility and then as it grows, you take on more or as you grow, you take on more responsibilities.

Mary Right, there’s some reciprocity there for giving back.

Louise Right, exactly. There’s a kind of responsibility to the group that is making this thing that you do possible, you know? Especially folk dance, it’s so entirely reliant upon people being willing to do it you know, if not for free, basically for free. It is a thing that we do for fun, and I love the aspect of it that is kind of, for lack of a better word, anti-capitalist, right? It’s just like, yeah, you know what, this is a fun thing that we can do with very little infrastructure and we can do it almost anywhere. I mean, my God, in COVID, we learned that we could do it literally anywhere and nowhere. It’s just this incredibly malleable thing and so in some ways, it’s quite exciting. I mean for me to come home one summer and think, “What I really would like is an Irish set in my living room next week,” and for that to actually happen, is magical. I have to say, Oklahoma was a difficult place for me to live in I think is the gentle way to put it. And I relied on the dance community for a lot of support and care, and it didn’t universally give it. You know, Oklahoma’s dance community reflects Oklahoma as a social climate more generally but key people really did. I think that really made me invested in making this community sustainable, right, like in contributing to it. Because, I think across the country, across the world, social folk dance is a space for people who don’t necessarily have easy social places in the rest of their lives. So, I enjoy organizing on many levels, but I think part of it is about creating those spaces for people who don’t have spaces. Or who don’t have the most nurturing kinds of spaces, or even just sort of well-rounded spaces. And to do that outside of a system where everything is sort of commercialized. I like reminding people we can make our own fun.

[ Clip of Louise calling the dance The Reminder by Louise Siddons at the London Barndance in London, UK with music by Portland Drive. ]

Dancing in the UK

Mary I think that’s such a strong element of our community is the many ways that people can pitch in and find a role or be involved in some way, it’s sort of very open source in that way. It sounds like you notice that as you travel around and is it similar in the UK? That’s a dance landscape I’m less familiar with.

Louise I feel like it’s like every community, the more you get to know it, the less you realize you know. I love the dance community in the UK because it is incredibly diverse. I can go from a weekend doing super complex 18th century dances to a ceilidh where it’s like drunk people being slightly chaotic, and everything in between. And those were both English examples, which is a bad example because I can also like go balfolk and I can go do contra and I can go to a club dance where I would do a little bit of all those things in one evening. There’s a lot of dancing to be done, but there’s also a huge cultural divide here between people who are very old fashioned about their expectations. Obviously gender is a part of that at the moment because that’s the discursive moment that we’re in. But there are other things, like some of them are really comforting: I know when I walk into a club to call their dance, I’m going to get offered a cup of tea when I arrive. Right? That doesn’t happen at contra dances in this country, only club dances.

Mary Yeah, so lovely.

Louise And they’re going to ask you what you want at the break, tea or coffee and they’re going to bring you whatever you asked for with two biscuits. It’s like there are such kind of old, old fashioned, that’s the word I used before and I’m going to stick with it, modes of being in the world. And as someone who is unrepentantly, I think, nostalgic for a time and place that never existed, I love that. You know, it reminds me of my grandmother and it reminds me of the ways in which foodways are about community building, it’s little things. At the same time those are the dances that made me invent positional calling because they are the dances where you would never in a million years be allowed to use something other than “men” and “women.” Like, I have been told off for asking someone to dance because their spouse is right there and what was I thinking?

Mary A different kind of old fashioned.

Louise Yeah. Like, there’s just a whole bunch of conventions. But then the flip side is like you have queer ceilidh, you have queer contra, you have all of those things happening here as well. I mean, obviously in the States there’s a debate around what we want our dance community to look like, what constitutes being welcoming and inclusive. But here it does feel different. Almost every dance, because as I accidentally became sort of the representative of positional calling, particularly in this country, people recognize me. The dance community in the U.K. is tiny so having done a few festivals people know who I am, so they see me on a dance floor and I don’t think I’ve been to a dance that wasn’t labeled as gender free and not had someone say something about how they didn’t think that this whole gender free thing was necessary. You know, the level of unsolicited feedback I get about gendered and non-gendered calling is massive. Because all of that happened, I think largely because of the pandemic, and we were all stuck having conversations instead of dancing. I don’t know, I haven’t danced in the U.S. since the pandemic. I have no idea if the same thing would happen if on a dance floor I would get accosted by someone every time saying, “I just need you to know that I think larks and ravens are ridiculous.” And I’m like, “It’s larks and robins now.”

But equally, you know, like I was at our local contra dance last Wednesday and unexpectedly, because the caller who is supposed to do it had an injury and I was splitting it with one of the other local callers with about two days notice so we didn’t really talk. We just were like, you do some, I’ll do some? Perfect. Great. That’s our plan, right? I show up and he is calling entirely positionally and he’s never done that before. And I didn’t ask him to and people in the room heckled him, tried to get him to stop. He was like, “No, I’m trying this thing and I’m going to stick with this thing.” I don’t know how old he is, but he’s definitely over 70 and I’m just like, you’re awesome, like, amazing. And I remember coming into my old club in London and they didn’t know I was coming. I didn’t know I was going until that afternoon. And again, this guy who’d been calling for longer than I’ve been alive probably is like calling positionally. He’s like, “I just want to try it.” It comes up in these weird ways where you’re like, the people you least expect are the people who are most excited about this new skill that they might develop. Even if they don’t stick with it, like exploring it and thinking about how it might help them. And I hope that that’s partly because I keep framing it as like thinking positionally will help you help dancers get better as teaching benefits beyond the gender bit, but for me as a dancer it just utterly changes the way that I experience the dance. It took me most of my life to realize how much the language we use around gender matters to me personally. And so part of me is like, you know what? If someone who’s 18 can have the opportunity to realize that at 18 instead of 38, more power to them. Like, why not do that for the world? But that also makes it more amazing that people who don’t have a personal investment are still kind of…that they get it, you know?

Mary I mean, I feel like it goes back to this sort of open source idea of…or it’s like the opposite of top down in a lot of ways, the way that our dance communities and traditions, it’s sort of the the classic definition of like a traditional art form. It’s funny how that’s often confused with like an idea of staying a static thing. I think people often confuse “traditional” with “the way it has always been,” when in fact tradition really evolves in response to a current circumstance, and led by the people who are doing it, and who need it to serve different roles in their lives. And not everybody experiences it that way and wants it to be that way. But it’s so cool to recognize when somebody is willing to say, “Oh, it has been this way for me and what’s this new part of it that I haven’t gotten to experience yet.” That’s so cool.

Louise Yeah, exactly. I mean, as I said before, I’m a historian, right? So I think in terms of kind of how change happens through lots of tiny little actions kind of coming together to create change that respond. Like I really believe in the idea of a zeitgeist in a way that’s probably horribly…like I should not say that as a professional historian. But I think it’s a really useful concept to understand sort of, why did multiple people…you know, I said before it was an accident that I became sort of one of the leading voices of positional calling. I think that was almost entirely because Brooke Friendly asked me to write the contra “Dancing the Whole Dance” book. I’d been doing some workshops, I’d been talking about it, but the book and the CDSS logo and the kind of publicity that that gets gives a kind of authority to me that I don’t necessarily…not that I don’t deserve, but what I’m trying to say is I think it’s not a coincidence that like Andrea Nettleton and Beth Molaro and myself, and to a certain extent, Brooke although really not in a contra context…but all of these people were starting to think about sort of: what does positional thinking have to contribute to a conversation around, not just how we describe roles on a dance floor, but how we think about what we’re doing on multiple levels. I mean, Andrea and I have had multiple conversations that are just about positional calling as a way to get people to dance better, which is why I’m so adamant about that aspect of it, because I know from teaching new dancers that their dancing is more fluid, faster, if they’re given these concepts that you don’t get when people are relying on certainly gendered role terms.

Positional Calling

Mary I just want to back up a little bit and introduce “positional calling” a little bit. I mean, I love how that flowed but I also want to make sure that if anyone is kind of new to some of these concepts, they’re able to follow along. Could I ask you to do that and kind of frame for us how you started putting together and kind of naming this set of concepts and tools that is now…is it “positional calling?” I’ve also heard “global positional calling?”

Louise Yeah, so I wish I knew where positional calling came from because I kind of just started using it because everyone else was using it and it’s not entirely accurate. I had someone in a workshop who I really should go back and see who it was so I can give her credit for it. But she liked “relational” as a term for it, which makes so much more sense. Right? Like if I could go back in time and start over, I would call it relational calling. Because, first of all, being very explicit about the fact that in a swing, one of you always ends on one side and one of you always ends on the other, right? And then like, “Okay, what information do we have?” I am devoted to the ballroom hold, because if you swing with a ballroom hold, then you have a hand that you can use both to point in the direction you want to face and to let go so that you’re on the correct side. It’s a weird rule, right? It was fascinating because Chris Page, when he was talking to you, attributed this rule, he said it emerges in this one dance from 1942. And I’m like, What? Really? Can we pin the rule based swing to one dance in one moment? That is fascinating to me, I’m not convinced. But I think maybe what he was saying is. that has always been the swing rule, like in a square dance.

Mary Right.

Louise To realize that you can use it as a way to progress a contra dance was quite new in that moment because if you think about a lot of chestnuts, it’s like you lead back up and cast down and that’s your progression. In any case, that is caller nerdiness in the extreme or maybe historian nerdiness, I don’t know. But it’s the only figure in all of social folk dance as far as I know that has this random rule attached to it about where you end it. So unpacking that for new dancers and just being like: then when you’re standing out at the end, what do you do? You swing and you face in and that is so much more comprehensible than “Remember to cross over.” Like, “Oh, God, another arbitrary rule I have to remember?” No, you don’t. But similarly, if it’s going to be a chain across by the right, it’s going to be the person whose right shoulder is on the outside. This kind of information is not the kind of thing I would say in a walk through. But in a workshop about dancing positionally it’s the kind of thing that I would say. Like, if it’s a right shoulder hey, it’s going to be the person with their right shoulder on the outside. If it is an allemande right, it’s going to be that person. There are patterns here, like your outside hand is the functional hand. If you teach dancers those kinds of rules then they start to look for them and feel them. And, you know, for me, now, if someone says “Chain,” I don’t think, “Oh, that’s my right hand, right.” I just put out the hand and as someone who’s really bad with lefts and rights that was like a key learning moment for me.

And similarly in the same way that we treat roles as these kind of discrete pieces of information, we treat figures in a walk through as discrete bits of information. Like if you’re doing the walk through, you’ll have a caller say, “Chain across,” and everyone chains. Now do a hey, right shoulder start, and then people… So they stop and they start. And for me it was sort of, how do I teach this in a way that emphasizes the transition between figures rather than emphasizing the figures. And so all of that obviously gets elaborated into a whole bunch of things about how you do your programing and how you write your walkthroughs and is there an introductory workshop and what do you teach in it? But yeah, as I said earlier, I think to me, what was the key insight was that it was making dancers dance better and learn more quickly. And so what had started out as a strategy to call without reference to gender became a strategy about teaching more effectively. At that point, I was interested enough that I was running workshops and then Brooke asked me to write the book. It’s just become something that’s continually of interest to me and something that is interesting because it’s changing all the time. I keep saying to people when I run workshops, if I wrote the book again it would say a lot of things differently and so the book for me is like this moment in time of like, this is what positional calling looked like when I wrote it a year ago.

Mary There might have to be some further editions, which is always true.

Louise But that’s the folk process, right? It’s like I’m going to put this idea out in the world, and then you all are going to make it better and that does happen, I think, organically by people discovering what works and what doesn’t.

Mary You’ve alluded to it kind of already…but what do you see in a dance evening when you are able to call the whole thing without reference to any roles. So when you’re calling completely positionally, what do you see or experience in that evening of dance, kind of as a whole?

Louise I mean, I think it depends who I’m calling to. I guess in my head, I’m thinking, “Do I see anything different than I saw five, six, seven years ago?” I see differences in my own programs. I’ve been very intentional about trying to call three-facing-three dances and dances that are not binary. It definitely took me down a whole weird rabbit hole of dances that aren’t just two people dancing with two other people and then progressing. And realizing the long history of that, you know, like the very first edition of Playford had a three-facing-three dance. So in 1651, we weren’t coupled necessarily. And consistently, it’s always a minority of dances, but they have always been there in every tradition and to me that says there has been a continual community need for dances that go beyond the binary structure of a duple minor set. So for me as a historian, but also as a caller, that’s interesting. For part of the pandemic, I lived with two other people and we were Zoom dancing and trying to adapt things for three in a way that made me think differently about choreography and was sort of exciting. I think that there is a danger in any group activity for things to narrow. You know, for me, it’s one of the ironies of the controversy over positional calling, people can’t see my scare quotes, but I think that at this point the word “controversy” deserves scare quotes when it comes to gender free anything in contra.

But everyone says, “Oh but you have to narrow down your repertoire because not everything can be called positionally.” And I think, especially if the room is on your side absolutely anything can be called positionally that’s a contra dance. I also think the people saying this are people who are responsible for narrowing down the repertoire so significantly, massively. In the 15 years I’ve been dancing, it has gone from this incredibly rich field to, like every dance has a partner swing and a neighbor swing. So what are you talking about, narrowing down the repertoire? But red herrings aside, I think that certainly it expanded my repertoire to be trying to dance with two people and then to think about, well, how has this happened historically? I think that’s the other thing that’s sort of important to me is that people frequently turn to history as an excuse for gendering dance terminology. I love history, I think history is fascinating. But I think that if you’re going to talk about history, you have to talk about the whole history, right? We’ve seen that again and again and especially in the past few years right? But whether it’s Phil Jamison talking about the African-American roots of contra or squares or people talking about trans identities in 18th century British theater. There are all kinds of ways in which history is not straight and history is not straightforward, in the way that people who rely on it as an excuse for being hidebound in their thinking try to make it. I think, if anything, we should turn to history to make exactly the arguments that we’re trying to make.

Mary So you said you kind of started engaging in this exploration to really address something that you were experiencing going to dances yourself. And so you were kind of like, okay, like this is…I always hesitate to use the word like “problem” to solve, but this is the challenge, this set of circumstances that you wish could be different.

Louise I mean, I think it’s just like there are so many layers to it, right? So in Lansing, I don’t know how to tell this story, I never told this story before, which is kind of funny now that I think about it. But, there we were, a group of us went to a contra dance and there was a woman there who came by herself. I would say sort of obviously enough queer that I was willing to take that risk of finding out. But yeah, so there we were and she was new to contra dancing and so I asked her to dance. I was confident enough at that point that I was like, I can help new dancers succeed at this and it’s something that I enjoy. And also, you know, she was gorgeous and whatever. So there we are, I’m like, “Oh, I’ll be the gent because you’re new.” And like, what is that about?

Mary Oooh, yeah, there’s a lot there to unpack.

Louise There is so much there, and yet people do it all the time. And it’s like, one of these roles is not harder than the other. I don’t know, even if it were is beside the point, because, in fact, they are symmetrically difficult. They are equally sort of complicated or equally not complicated. But so like the internalization of that hierarchy when it has nothing to do with the choreography of the dance, I think was something that I didn’t recognize until it was taken away. So we went gender free at the Stillwater contra and that was my student group in Oklahoma and they didn’t like…I’m sure it was still larks and ravens in 2017 when they switched. And so they were like, “We’re going to come up with our own terms,” and I said, “That’s fine, but we have to come up with something…” Basically they came to me and said, “What are the rules for new terms?” And I said, “The rules are one syllable, two syllables because then I can sub them in without thinking about it.”

Mary Can I ask, was the student group a queer student group or just a group?

Louise It was just the student contra group.

Mary Just a general student group, but that was something they wanted for the structure of that group.

Louise Yeah I don’t want to put words in their mouth, but I think basically it was like, they were almost entirely women. We had one guy on the committee at the time and they wanted to dance with each other and they felt obligated to line up in hetero pairs if that was possible at the dances. And I think even though there were some dancers who would switch roles, like from Oklahoma City who would come to our dance…they weren’t sort of clear necessarily on when and whether that was okay…yeah.Mking sweeping generalizations, I would say that my students at Oklahoma State really liked having permission to do things. So I was like, “Okay, you can vote on new terms,” because they wanted to make sure that it was kind of democratic, how they chose these new ones. So we did a dance where the first half I called gents and ladies, and then in the break they had the vote. They had like a giant poster with all the options and then the second half I would call with whatever we chose. So they chose Chutes and Ladders.

Mary That’s really fun.

Louise Yeah, it’s funny because it doesn’t translate, like in the U.K., the same game is called Snakes and Ladders, and it’s snakes that you slide down. So I have to explain it all the time now, in a way. But anyway, so we were Chutes and Ladders. We switched over and it was amazing to me, like the same room full of people, right? And they had all been dancing one way before. And then the break happened, we voted Chutes and Ladders and almost the first dance, probably the first dance, people were turning to each other and going, “Which role do you want to dance?” And they were dancing with each other, like in completely heterogeneous kind of partnerships. Like it was just like, “Oh, I would like dance with you, let’s line up and I’m going to ask you.” And I’m like, this is making it so obvious that all the people who are like, “Oh gents and ladies, it’s just a role term, you can dance wherever you like.” Like, we really only meant it as a community in terms of okay if you’re at a dance weekend and you’re kind of hot shot, you can do cool switching stuff and you can do chaos. But at a regular dance, we mean well, if you’re going to dance with someone of the same gender, it’s fine. It wasn’t really an enthusiastic, like you can learn both roles. And indeed, if you want to be really good, you probably should learn both roles.

Mary That’s interesting to think of that role switching as a sign of like aptitude or, you know skill as a dancer rather than just doing it like a way that you can dance, that you can be doing the dance. I hope…I think, it’s just different across the board in different places and stuff.

Louise It is, exactly. I mean I think there are places where certainly…but it’s tricky because for me when I dance outside my local community I’m almost always at an event that is experienced dancers. Like I’m hardly ever, as a dancer, in a room where there are a lot of new dancers. I’m really hardly, hardly ever now that I’m here, in a room where that’s true and also, they’re calling gender free. I did the London Barn dance about a year ago, which is the big contra dance in London and frequently has like huge groups of new people turn up at some random point in the evening. So I had a group show up, maybe like 12 people about two dances before the break. They watched a dance and they danced a dance and it was a little bit terrible and so I offered in the break to do like an intro workshop for them. I didn’t fully think through the fact that I did because I’d been calling positionally all night. I did a positional intro, but only the new people heard it, and I think most people in the room didn’t realize I was calling positionally because people fill in the words they expect to hear. And so having very carefully taught them kind of how to swing and where to end the swing, there was one couple that kept getting switched by all their neighbors, like “Oh, no, you’re in the wrong place.”

Mary Because they were assuming something…

Louise Because they were in the right place and they kept being really confused. It’s like, “No, but last time I wasn’t over here why are you putting me here?” So it wasn’t disastrous, it was just like a nice reminder to me that it helps to be explicit about what you’re doing.

Mary Right.

Louise So everyone in the room is on the same page. But this is what I mean, that that dance I would say is still on the conservative side and it’s almost entirely gendered. Whereas I can call in spaces where you absolutely cannot look at the floor and tell who’s dancing what role. Which is another huge thing for me, thinking positionally and teaching people to dance positionally is like, if you get screwed up then you can just seamlessly dance the other role because if you hear chain across and you know you’re aware of that person who’s chaining should be, even if it shouldn’t be you, you can just do it and figure it out later. The swing will fix you but accommodate in the meantime, which is a complicated skill to learn. But I think giving people the language and the concepts and a frame for how the dance geometry works is so incredibly useful.

[ Clip of Louise calling the square dance Square Line Special by Gary Roodman at the Brighton Gender-Free Contra+ dance in Brighton, UK with fiddling by Linda Game. ]

Dancing and social change

I was married briefly and I was at a dance with her and some random stranger guy came up and didn’t say, “Can I dance with one of you?” But said, I think I was in the gents role. He came over and he was like, “I’m going to be you.” I was like “Whaaaat? No, you are not.” And he’s like, “But you’re two girls dancing together.” And I was like, “Yes, yes, we are.”

Mary And that is what’s happening.

Louise “And you are from the 19th century.” Like, except I don’t want to blame history for this because Jane Austen’s favorite partner was a woman. So, like, don’t even, just get away. I think on every level there’s this kind of like, why do we bring that baggage onto the dance floor? Why are we bringing in kind of patriarchal hierarchy to a dance that doesn’t have one? Why are we making assumptions about things that are irrelevant to the dance? You know, so I think that there’s just ways in which as we learn and grow as a society, we can also hopefully do that on the dance floor.

Mary Yeah. I think it’s so wonderful to see the interplay between our dance spaces where we in many different ways have sort of…even though there’s a lot of challenges to encounter, it’s not that it’s going to be like a smooth, linear thing, but there is at least this mechanism of community involvement. And anyone, from wherever they stand in that community, is a valid person to raise a point or ask for a change or try to make a change and then to sort of see how maybe that’s happening because of larger societal things happening. I also like to hope that that flow is flowing outward as well. You know, that there’s a give and take, no pun intended, from our dance spaces and kind of our larger social spaces. Because so many people do feel so in touch with themselves in a really powerful way on the dance floor and then that’s a good starting point to sort of try to encounter and learn from what someone else is bringing into the space. I don’t know I feel like that was a confusing thing I just said.

Louise But I think you’re really right that people take away from the dance, lessons that they do apply to real life. I mean, that’s in some ways kind of the privilege of, I say the “privilege” of having a marginalized identity position is that you get to see…

Mary How ironic!

Louise [Laughter] Yeah, it’s also one of the sources of the most frustration. But, I mean, very legitimately, I think it has been a privilege for me when people feel safe being vulnerable, because a lot of people don’t have people that they can talk to about things. And so at least in my experience if I’ve been dancing with someone for ten years or more, I am someone, they’re like, “Oh, I have all these questions and all this frustration about this thing that’s happening and you seem to be stuck in the middle of it, and a proponent of it even, and so I’m going to ask you all these questions.” And it can feel quite hostile I think at times, like people don’t realize what they’re asking, but if I’m in a space where I feel like this is a conversation I’m equipped to have in this moment, then I do try to have it as sort of openly and genuinely as possible. Because I’ve had people come back to me and say “You know, my niece is trans and I never understood that.” And it’s like, if dancing, if gender free dancing helped you understand that, that’s so powerful. And if anything I said helped that process happen like that really does…I don’t want to minimize the level of alienation that people feel in dance communities, but every now and then you have that kind of interaction and you’re like, “Oh, yeah, we all kind of have a role to play in this.”

Looking to the Future

Mary What’s on the horizon for you right now? I mean, of course, acknowledging that we’re all sort of still in the process of finding our bearings again after three years of pandemic and figuring out what’s going on and also kind of integrating the things that we learned over that time. It sounds like you learned a lot even from just staying connected over Zoom and the different ways that we still maintained and participated with our dance communities. Also I wanted to make sure to highlight what you already mentioned, which is that you have just published a book on positional calling in partnership with CDSS. We’ll definitely include a link in the show notes so people can check that out, but that’s a whole bunch of factors that may or may not be at play for you, but in general, what do you look forward to and what are you moving towards in your caller life these days?

Louise It’s a really good question. I am super grateful that we did start dancing very soon here in the UK. I think it’s intensely problematic. It was sort of physically shocking to me how when the government regulations went away, everyone immediately stopped masking. I was commuting into London and I’m like, I am not taking my mask off on this train because it was illegal to have it off yesterday and just because it’s legal today doesn’t mean like biology has changed. So that was eye opening, I think, in terms of sort of cultural experience. But it did mean that I’ve had a lot of calling opportunities since I moved here and I’ve leaned into them because I think everywhere I’ve lived, the dance community has been my community. I do think of that as kind of my primary social network. So it’s been nice that we’ve been able to do that so much. I was also really lucky some of the workshops that I did online in the pandemic meant that people here knew who I was more than they had before and so I got invited to call at festivals and things straight away, which was very, very, I think, supportive and sort of incredible for me. What that meant in terms of where I see myself going as a caller is that I could have conversations with people who are organizing events about sort of what I do and why I think it matters.

And so this spring at the Chippenham Folk Festival, I’m doing workshops on positional calling that I could say to the organizer, you know, “I think it’s really only half of it, is the calling, the other half is this idea of positional dancing. What I really want to do is a positional dancing workshop.” And so he said, “Yeah, okay, we’ll put that in too.” That’ll be the first time I’ve done a positional dancing workshop in person. I think that that’s quite interesting. I’m very much looking forward to that and kind of making that into something that we think about in part because what I’ve realized running caller workshops is that they aren’t things that come naturally because they’re not the way we were taught. You have to retrain yourself to think that way and teach that way. And so having a workshop where you can do it as a dancer then allows you to transfer that sort of physical knowledge into when you’re thinking about it. I do love running workshops. My firm belief is that I enjoy teaching because I learn so much from it. I’m looking forward to that in a variety of ways. I’m going out to California to do Heydays, so I’m looking forward to doing a bunch of English calling in addition to contra. I like that I get to do a mix. I’m really sort of happy about that and I’m not good at doing nothing. So I think dance is a really important way for me to do something very different from my day job but still be working.

Mary Still be occupied, channeling your energy. Well, it sounds like there’s no shortage of projects on your plate, it’s really exciting. Let’s see, I usually have three questions that I close with, but before I do, is there anything that we haven’t covered or anything that I just haven’t asked you about?

Louise I mean, the thing about positional calling. I always get asked in workshops, “Why do you think positional calling is the answer?” And I try to say every time and usually repeatedly, I do believe in the power of repetition, that I don’t think it’s the answer. I think that it is an incredibly useful and interesting and fun strategy for teaching and calling. But that idea of like, we find the ultimate solution and then we’re done is so antithetical to the idea of a living tradition. Pete Seeger has this gorgeous line that I never remember about how folk is a process, not a thing. Absolutely this is where we’re at now. But I sort of love that the positional calling book is already out of date in my head. I still think there’s a huge amount of value in there, but part of its value, most of its value is about how it starts a conversation that I hope will then have more people than just me coming up with answers.

Mary I think that’s happening from my perspective.

Louise Yeah, I think it is too, I love it. I have this huge file of notes of things people in my workshops did better than I thought of doing. But the other thing I always get asked is about squares. Can you call squares positionally? And I always again say that I am not enough of a square dance caller to answer that question. My instinctive response is no, that the architecture of squares is 100% built around this binary relationship and you have to name those somehow. But equally, I keep saying to the square dance callers who come to my workshops, you all know more than I do. Like if someone wants to organize a “Let’s figure out if we can call squares positionally” workshop I am there for it. I would love to be part of that conversation and in an audience almost kind of way because I know nothing. But I just think every time you think through something from a new perspective, you learn something, even if it’s like, “Wow, you’re right, Louise, this is not going to work.” We would all learn so much about how squares are put together. So please someone, organize that.

The Binary and Social Dance

Mary I’m so grateful just for this opportunity to hear from you and start to learn a little bit more about what’s happening with positional calling, because it’s certainly on my radar. For me personally, I’ve definitely been in the gender free role terms realm very solidly for many years. It’s so interesting to sort of trace the different points, like when did I start to just not be able to look at a room full of new dancers and say, “Choose who’s doing the gents role and who’s doing…” Like just not being able to do it anymore in that context. And I’m so appreciative of the many different people who are talking about this and giving us new ideas to try and play with. And for me, positional calling is like starting to come into the sphere of things that I could play with and learn from. One thing that I’m still grappling with just as a total beginner thinking about these concepts is…you know you’re kind of describing in squares… This whole challenge of getting away from binary thinking, which we are all trying to do in many ways as well. But describing squares as sort of depending on a binary. Like in some ways that could be argued for contra, like having two pairs in a minor set. And sometimes, I probably wouldn’t have called it positional calling, but I have in many situations tried to think how can I describe this without role terms, you know? You know, for all the reasons that we want to do that but I often do come down to like, “a right hand side and a left hand side,” or in a circle mixer, it’s the “inside person” and the “outside person.” To me, I’m like, isn’t that still a binary unit? How do you sort of expand out of that in the lens of positional calling?

Louise Yeah, I mean, I think absolutely any dance that has a couple at its core is going to have a binary geometry, which is partly why, as I started to think about this, I was like, “Oh, if we stop focusing on that binary as the core dynamic of the dance, it opens up other possibilities, right?” And so whether that’s you have two partners instead of one and so we introduce a three-facing-three, which like I had always been using three facing three dances for things like teaching a roomful of inexperienced dancers how to do contra corners because it’s so much less confusing in a group of six than in a long line. There’s nothing inherently wrong with a binary. Like even from a critical theory kind of super academic perspective, the problem with the binary is the hierarchy.

Mary Yes, the “gents role because you’re new” kind of thinking or the “lead” and “follow” thinking.

Louise Right, if you’re a gent, you’re a lead and you are the one who can initiate flourishes, etc., etc. Like all of this baggage that comes into the dance because we’ve imported the hierarchical part of this binary structure. I remember being an undergrad in some feminist lit class being presented with a list of like here are binaries, we can put all of them in a hierarchical relation and thinking like, “Well, only if you value that side of the list more than that one right?” As someone who consistently roots for the underdog, let me tell you about the positive power of losing. So I think releasing ourselves from the expectation that every binary has to have a good one and a bad one, whatever that means, right, is quite important. It’s not the binary itself that’s a problem. It’s just, can we make that egalitarian? Can we make it something that everyone has access to? While I fully understand the advice that you only pick one side and stick with it if you’re a new dancer at a contra dance, I also think there is value to saying pick one side and then if you didn’t love it, try the other side. You’re new. You’re going to be messing up all the time anyway. There may be a side that feels better to you and that can be for all kinds of reasons. And the third thing that I get asked all the time and that I say to people, although I have to say this happens much more in the English sort of side of things is that people say, “When you take away gender, you take away the romance.” And setting aside the very obvious, “Only for you, not for me, right?” I think it’s really important that we remind people that they bring something to this, right? Like, if you want romance, you can bring that, obviously, with the consent of your partner, but that is something that’s in you, not in the call. We all have so much freedom to bring whatever we want to the dance, which is why dancing is powerful. Like, some days I’m using it as escapism and other days I’m in the mood to just like partner with only new dancers all night. It’s impossible to know why people are showing up and so we have to take responsibility for bringing ourselves, I think.

Closing Questions

Mary I love it. So I usually close with three questions which are just sort of my little survey of a few things that most callers have practices or thoughts around. So the first one has to do with dance callers being also kind of collectors or curators of dance repertoire and needing to have a way to file or keep our dances. So I’m curious what you do in terms of dance notation. Are you digital, do you have cards or binders or what’s your strategy?

Louise I started out with a Word document when I was brand new and quickly switched to a FileMaker database because I had used it a lot at work and it’s fully customizable and searchable and all the rest of it. So I had a FileMaker database for a while, which was the closest to ideal I think one could get in terms of me traveling a lot. Portability, accessibility, you could back it up in a bunch of places. I can’t really remember why, to be honest but I started handwriting cards and I realized that I love the experience of handwriting. I mean, I’m an artist and an art historian, and I love craft and so crafting my cards becomes this, like, really lovely thing. But also, I remember the dances better. Science tells us that if you handwrite things, you remember them and I was really having an uptick in my calling and finding that physical aid to my memory quite useful. I also developed this sort of arcane color code, it’s not color coded. I feel like we have seen examples of color coding on this podcast. I have two colors, black and blue, but they mean something to me and that was not as easy to do online and sort of finicky whereas when I’m writing out a card, I can just switch pens very, very fluidly. So I have paper cards. I’m a pretty avid collector, I try every dance I call to call at least one dance I haven’t called before. It’s a way to stay kind of current and interesting, and especially because I’ve become interested in these sort of more egalitarian choreographies. My dance box is changing. People are writing really interesting new dances now and so trying to keep on top of it all. Anyway, so yeah, mostly paper. I’m trying to figure out how to transition more effectively to kind of hybrid model, but I think it may be just a folder full of photos of my cards, which is not great but could be worse.

Mary Just another thing to do in hybrid these days, like we’ve all learned that.

Louise I have a digital list of all my programs and I have to say the Caller’s Box has revolutionized my whole attitude towards this. I once got called in to do a gig at the last minute…

Mary …and the Caller’s Box is an online database.

Louise Yeah, it’s great. I had my program on my phone, but none of my cards. I mean it was just an old program where the day got canceled. So I’m like, “Oh, you need me to call something tonight, huh, I have a program right here.” So I literally went to a stationers, bought cards, bought a file folder thingy and was writing the cards out again from the Caller’s Box database on the way to the gig. It was slightly crazy. But yeah, so, yeah…tools of all sorts.

Mary Yeah there’s so many! Nice. When you’re going to a gig, do you have any pre- or post- dance rituals that you have to kind of prepare for or wind down at the end of the night?

Louise I don’t, really. No, I feel like I’m actually more ritualistic when I’m going as a dancer.

Mary Oh, what’s that look like?

Louise Well, this is the most alienating answer I could ever give in a public forum but I really prefer going to dances by myself. So, people offer you carpools and you’re like, “No, I’ll take the train.” I mean, I never do, right? I always say, “Yes, I’d love to go with you instead.” But I really love going to a dance and just getting a sandwich or something really easy to eat and kind of having half an hour to myself before I go into this intensely social space. So yeah, whereas I feel like as a caller, I mean, you can’t have time to yourself ahead of time, really, because you’re there doing soundcheck and what have you. But that has its own kind of ritual character, right? Like for me, I don’t need to build in rituals when the soundcheck is a ritual of its own. So it’s interesting, I hadn’t thought about it before, but I have to say, Jane and Andrew, who run the London Barn dance, have a very lovely wind down tradition of like wine and cheese that I think every caller should have.

Mary Nothing wrong with that. No, and I totally get that, I also feel pretty introverted in general and often have that tug of war between carpooling versus, for me it’s more on the other end of things. Like there’s part of me that wants to know that if I’m ready to go home, that I can go home, which, you know, where I live that usually requires a car. It’s a balancing act, all of it.

Louise I have to say, one of the best things about moving here is that I left my car in the States.

Mary Oh, the dream.

Louise And it can be a real hassle. The last train back to Winchester is before London Barn dance ends so I rely on the kindness of friends frequently, but it’s also an amazing thing not to drive anymore. My girlfriend’s a musician and so she has a car and that also is a bit handy because I cannot actually do gigs realistically especially if you’re bringing any kind of equipment without a car. But the caller, we’re lucky cause usually I’m only carrying my mic and my cards.

Mary Yeah, traveling light. No, any time I’m traveling with a band or at an away gig, I just have so much, so much love and admiration for the musicians who just…it’s so much more involved for them to show up and do what they do.

Louise Yeah, exactly.

Mary And then, I mean, we’ve already talked about this a little bit, but I have sort of been tracking in these interviews whether people kind of identify as more of an introvert or an extrovert, because I’m kind of interested in how that plays out for people who have chosen to become callers. Because it does require being in the spotlight, being in groups of people. You’ve kind of touched on this a little bit but it sounds like you’re introverted but find some comfort in kind of having a defined role as a caller.

Louise It’s funny because I think, yes, definitely right? There is a way in which calling gives me a sense of purpose in a space. But I would say also, dancing does. I love so many things about folk dance compared to other kinds of dancing but I love that you can just know that you will dance all night if you want to, which isn’t true at a swing dance. I used to go to swing dance events all the time and sit out for three quarters of it because I was way too shy to ask people. And if people don’t recognize you they won’t ask you because they don’t want to dance with someone who might not be good, like, there’s such snobbery. That obviously also exists in the contra dance community, but not nearly as much. It’s not universal in the way that I often experience it as being in swing communities. I think that a part of my introvertedness is a real horror of making other people uncomfortable and so there’s that moment of when I realized that bringing my book to a dance and reading through the break was actually sending this message of like, “I have no interest in any of you,” and like, how rude it was perceived as being. Whereas I was just like incredibly naively thinking “Well I don’t know anyone here and they don’t know me why would they want to talk to me?” So I think also it sort of saves you from that accidental faux pas that I apparently live in horror of, which I think is a very introverted thing. But for me it’s the classic like, if when you’re with people…it’s not that. I don’t like to be with people, right? It’s just that I get exhausted.

Mary It takes energy, yeah.

Louise It’s interesting. I’ve noticed that events have started to have things like quiet rooms. I adore that, how can we make this accessible to everybody?

Mary I love it. Well, Louise, I’m so happy to get to know you a little bit more. Before we started, we were remembering maybe being at the first Elixir dance weekend, and we’ve crossed paths a little bit in other ways. But I hope that I get to be on the dance floor when you’re calling sometime, hopefully in the UK. I would like to make that happen for myself.

Louise It’s one of the best things about moving here is I can be like, “If you need a guest room…”

Mary Ha ha. Good to know.

Louise I think that you should have someone interview you for this at some point.

Mary You’re not the only person that has said that and I might be revealing some of my introvert tendencies, perhaps preferring to be on this side of things. I’ve been thinking about that because I’ve got my own stories too. But I just love this opportunity to talk with fellow callers and that Zoom is allowing us to connect and allowing me to connect with folks all over the place. So thanks for helping us visit some of your world and enjoy the rest of your day. Thanks for dropping by!

Louise Yeah. Thank you so much for having me.

Mary Thank you so much to Louise, for talking with me. Check out the show notes at podcasts.cdss.org to learn more and also to find a link to Louise’s new book, Dancing the Whole Dance: Positional Calling for Contra.

This project is supported by CDSS, The Country Dance and Song Society and is produced by Ben Williams and me, Mary Wesley.

Thanks to Great Meadow Music for the use of tunes from the album Old New England by Bob McQuillen, Jane Orzechowski & Deanna Stiles.

Visit podcasts.cdss.org for more info.

Happy dancing!

Ben Williams The views expressed in this podcast are of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect those of CDSS