Welcome to From the Mic!

“One night the caller wasn’t there and somebody had to call the dances and I gave it a try…”

~ Phil Jamison

In the debut episode of From the Mic we meet Phil Jamison of Asheville, North Carolina. Phil is nationally-known as a dance caller, old-time musician, and flatfoot dancer. He has called dances, performed, and taught at music festivals and dance events throughout the U.S. and overseas since the early 1970s, including over forty years as a member of the Green Grass Cloggers. His flatfoot dancing was featured in the film, Songcatcher, for which he also served as Traditional Dance consultant. From 1982 through 2004, he toured and played guitar with Ralph Blizard and the New Southern Ramblers. He also plays old-time fiddle and banjo.

In the debut episode of From the Mic we meet Phil Jamison of Asheville, North Carolina. Phil is nationally-known as a dance caller, old-time musician, and flatfoot dancer. He has called dances, performed, and taught at music festivals and dance events throughout the U.S. and overseas since the early 1970s, including over forty years as a member of the Green Grass Cloggers. His flatfoot dancing was featured in the film, Songcatcher, for which he also served as Traditional Dance consultant. From 1982 through 2004, he toured and played guitar with Ralph Blizard and the New Southern Ramblers. He also plays old-time fiddle and banjo.

Over the last thirty years, Phil has done extensive research in the area of Appalachian dance, and his book Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance (University of Illinois Press, 2015) tells the story behind the square dances, step dances, reels, and other forms of dance practiced in southern Appalachia. A 2017 inductee to the Blue Ridge Music Hall of Fame, Phil teaches traditional music and dance at Warren Wilson College in Asheville, North Carolina, where for twenty-five years he served as coordinator of the Old-Time Music and Dance Week at the Swannanoa Gathering.

In their conversation Phil and Mary talk about Phil’s roots in the old time music scene, how he first stepped up to the mic as a caller, and his philosophy and approach to leading dances. They delve into his research about the history of dance calling in southern Appalachia and compare the ins-and-outs of square dance calling and contra dance calling. Phil also shares some incredible historic recordings of dance callers and some tracks from his own musical collaborations. Enjoy!

Show Notes

Music and soundbites featured in this episode (in order of appearance):

- “Blizard Train” – “Blizard Train,” Ralph Blizard & the New Southern Ramblers (June Appal Records, 1989) Ralph Blizard (fiddle), Phil Jamison (guitar), Gordy Hinners (banjo), Andy Deaver (bass).

- Phil Jamison, Thomas Maupin, and friends flatfooting at the Clifftop festival in 2010

- Phil calling the Grapevine Twist square dance and a big set dance at the 2011 Dare to be Square in Brasstown, NC

- Historic recordings from Phil (view the entire collection referenced in his book here):

-

Mellie Dunham, “Chorus Jig” contra dance (1926)

-

Samantha Bumgarner, calling a Southern (big ring) square dance to “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss” (1924)

-

Ernest Legg calling “Chase the Rabbit” square dance with the Kessinger Brothers playing “Devil’s Dream” (1928)

-

-

“Zai Na Yaoyuan De Difang” (In That Faraway Place) – “March Celebration: Chinese-Appalachian Collaborations,” Jenny & the Hog Drovers and Manhu (recorded in Shanghai, China, 2017) Maddy Mullany & Clarke Williams (fiddles), Phil Jamison (banjo), Hayden Holbert (guitar), Landon George (bass), Jin Hongmei (vocal)

Other Links

- Phil’s website, where you can also order his book, Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance

- Square ’em up! A Dare to be Square event is happening in Dumfries, Virginia, May 6 – 8, 2022!

- Crazy about squares? There is SO MUCH on the Square Dance History Project webpage.

- Phil was featured in a great episode of Radio Lab exploring the history of square dance called “Birdie in the Cage”

- You’ll find some of Phil’s writing on dance traditions here on his website

The views expressed in this podcast are of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect those of CDSS.

Bonus Audio Clips

Click here to download a transcript of these audio clips.

Dance Cards and Set Lists

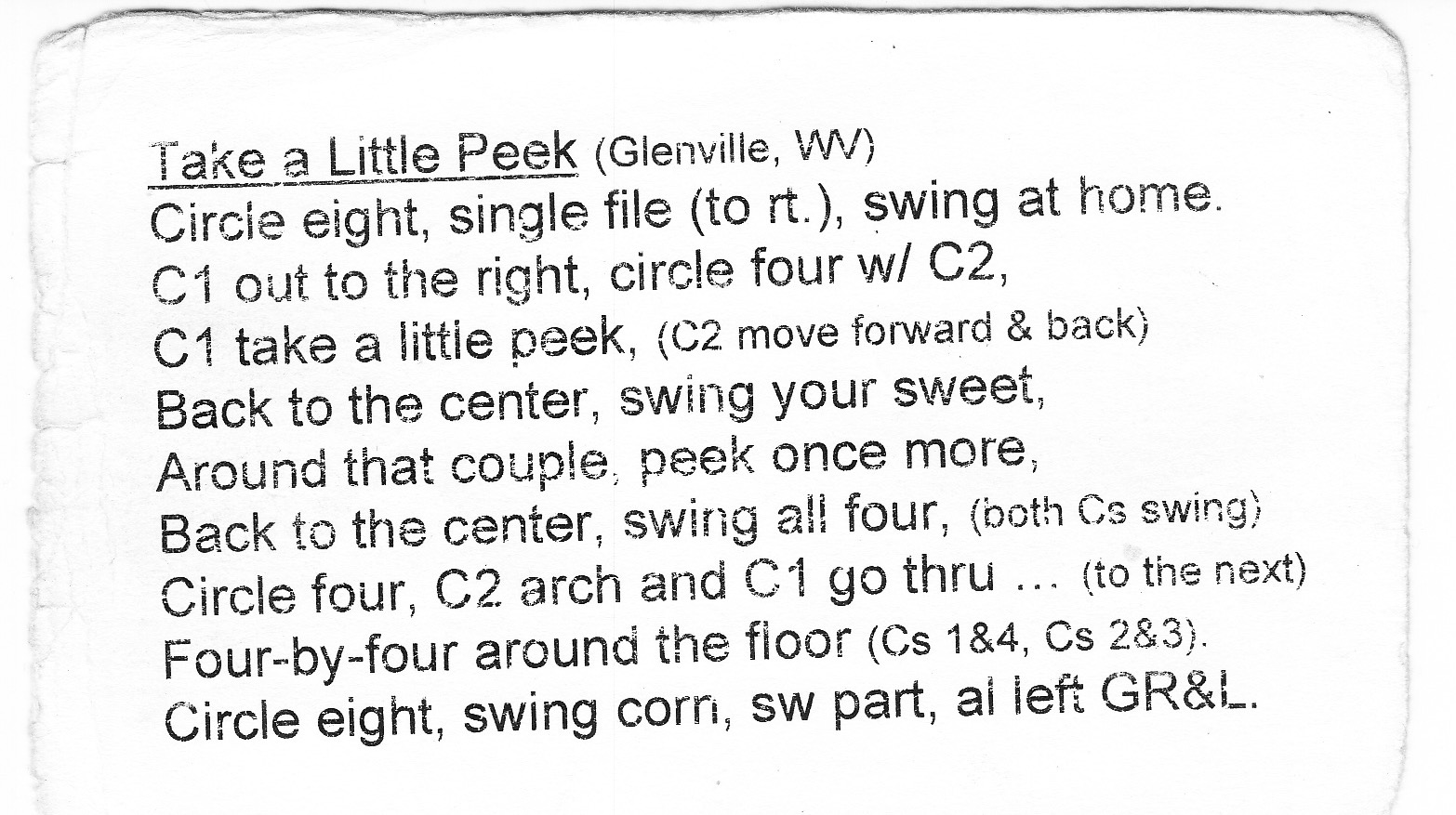

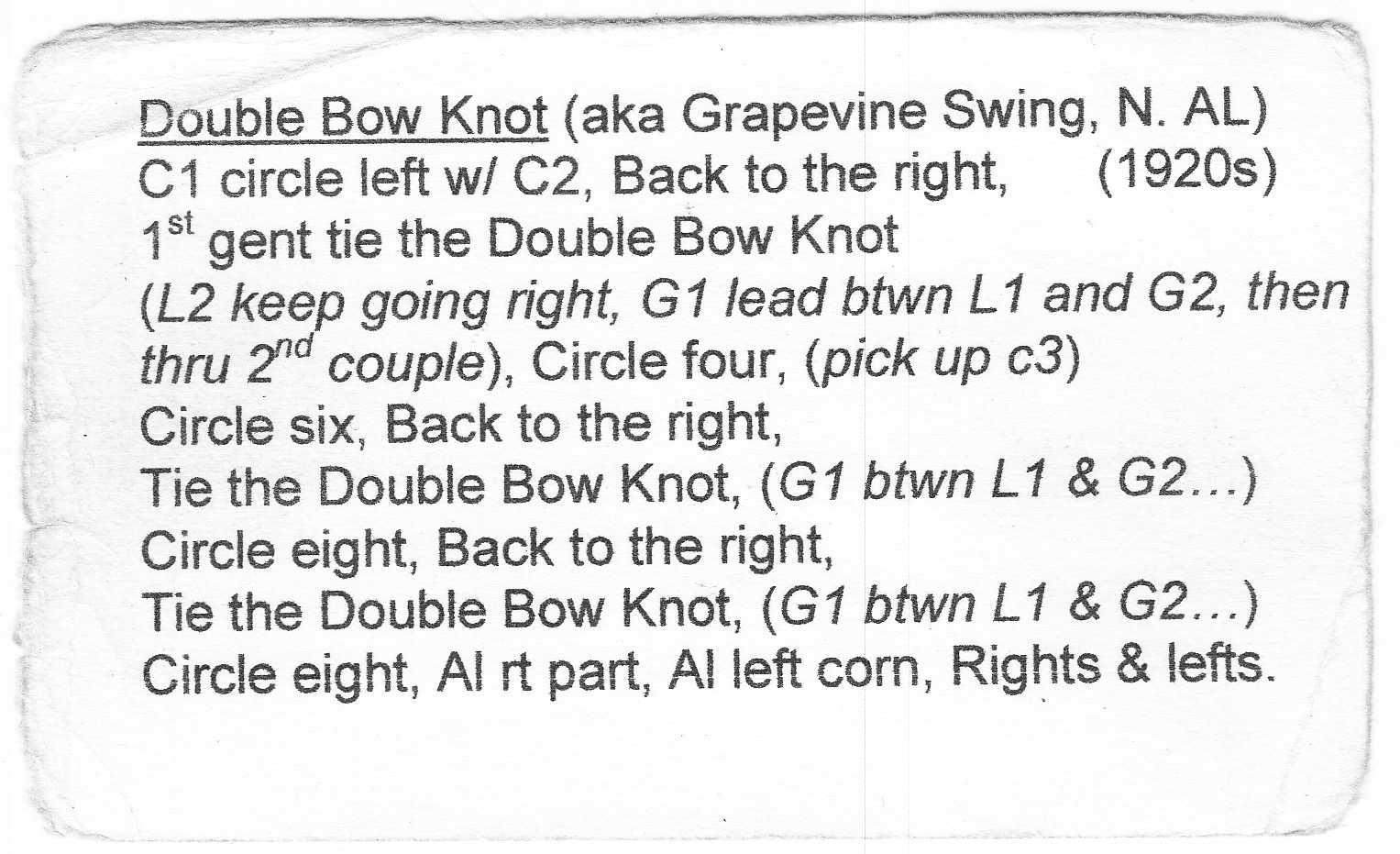

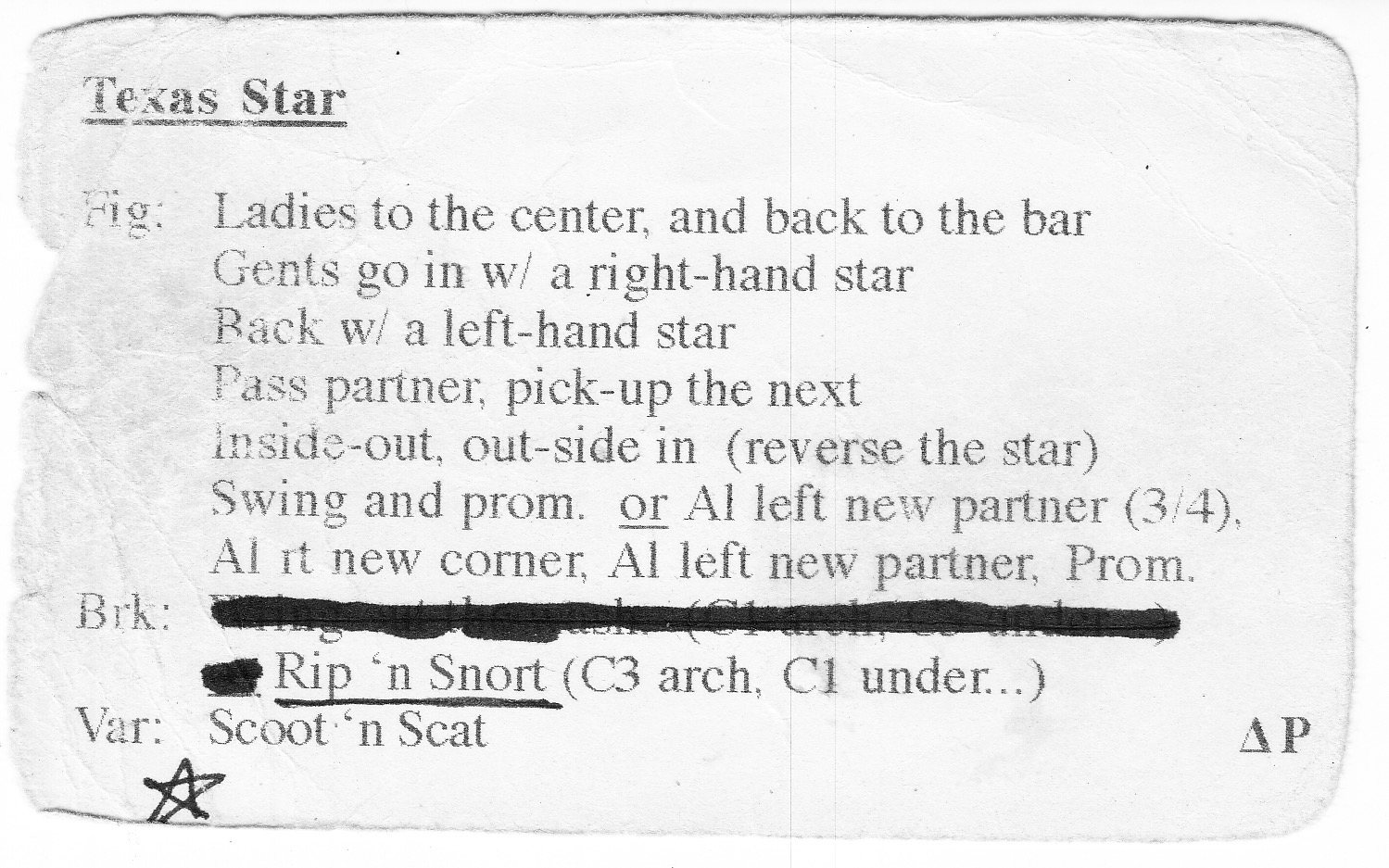

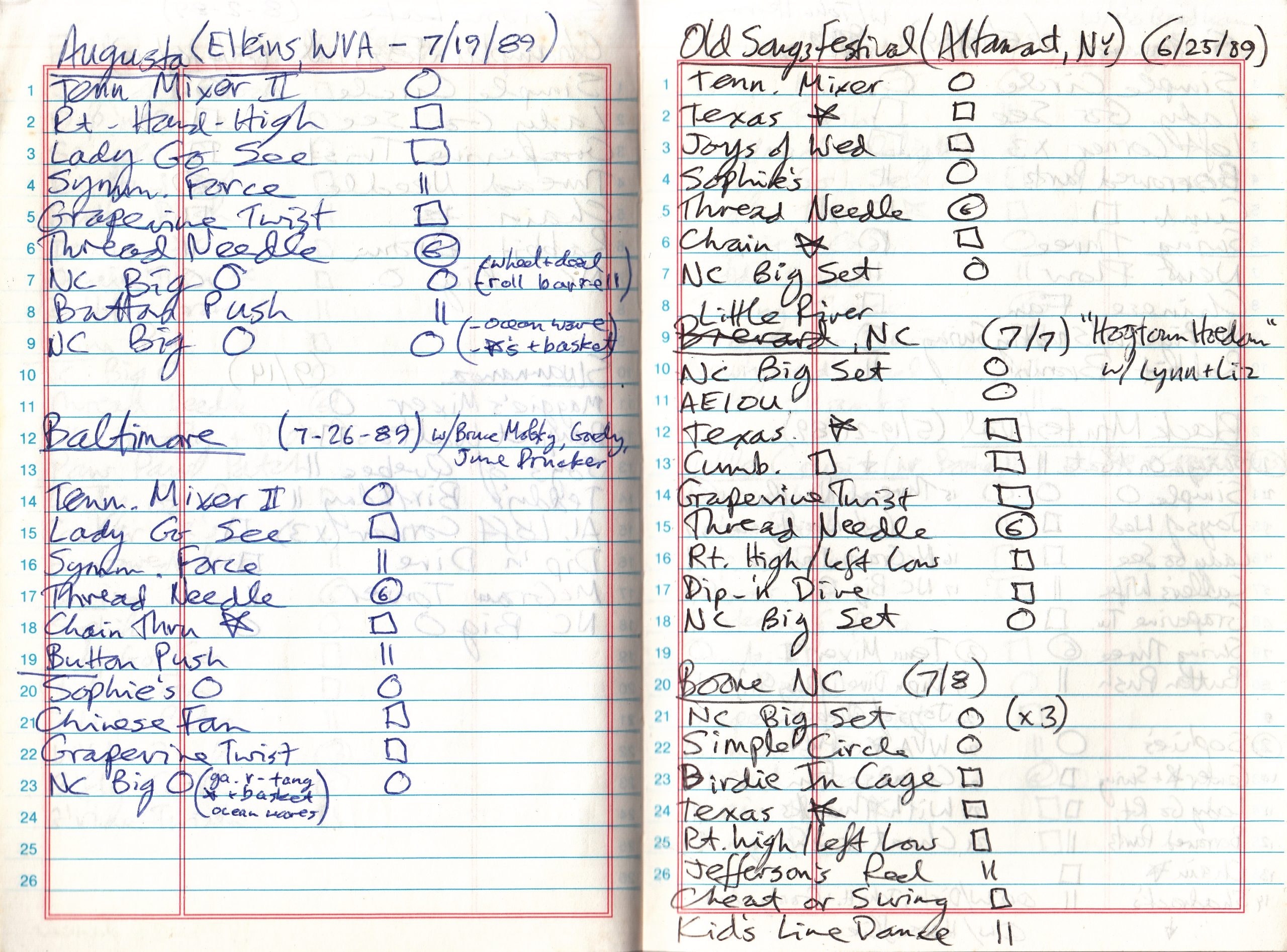

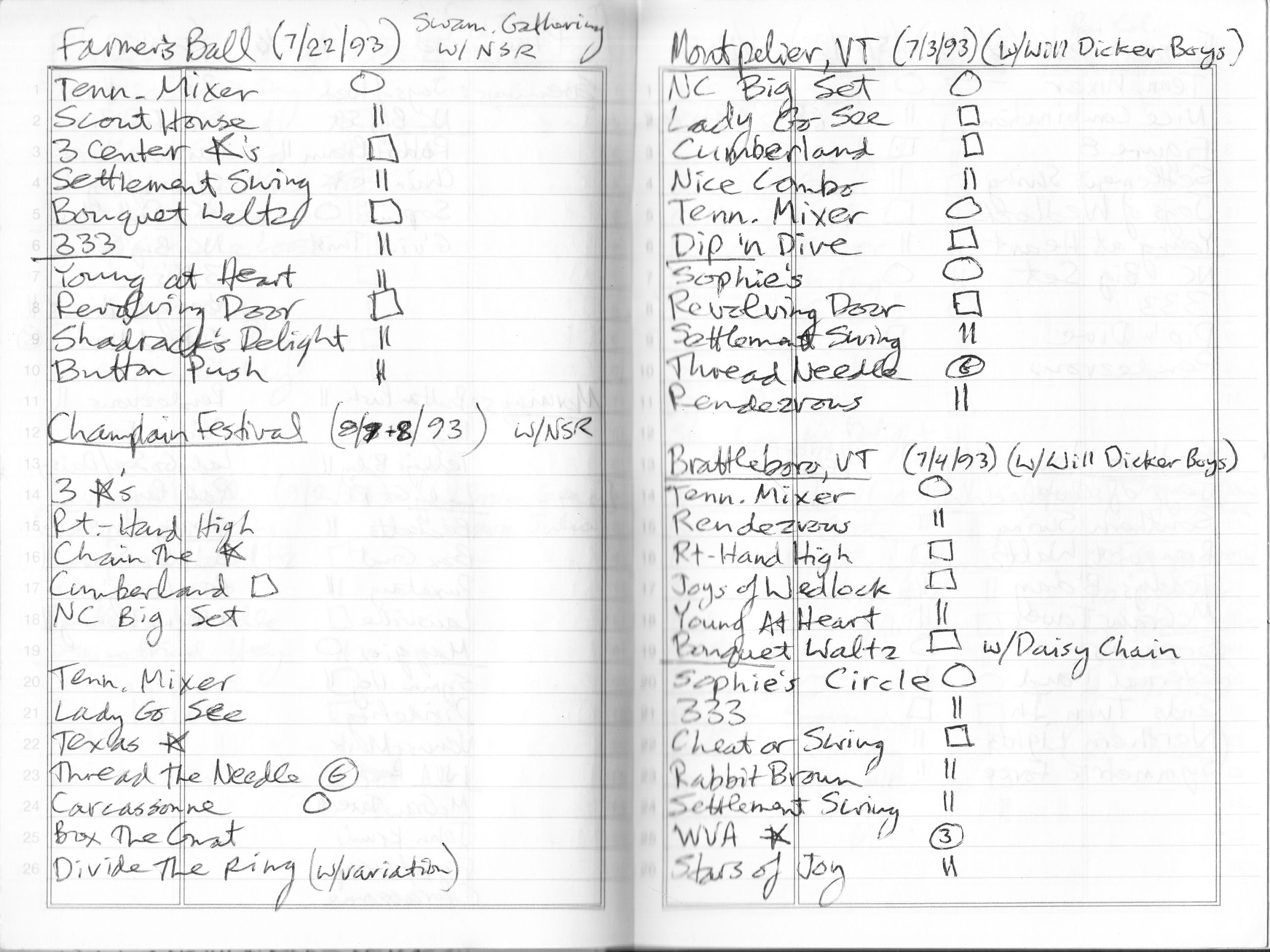

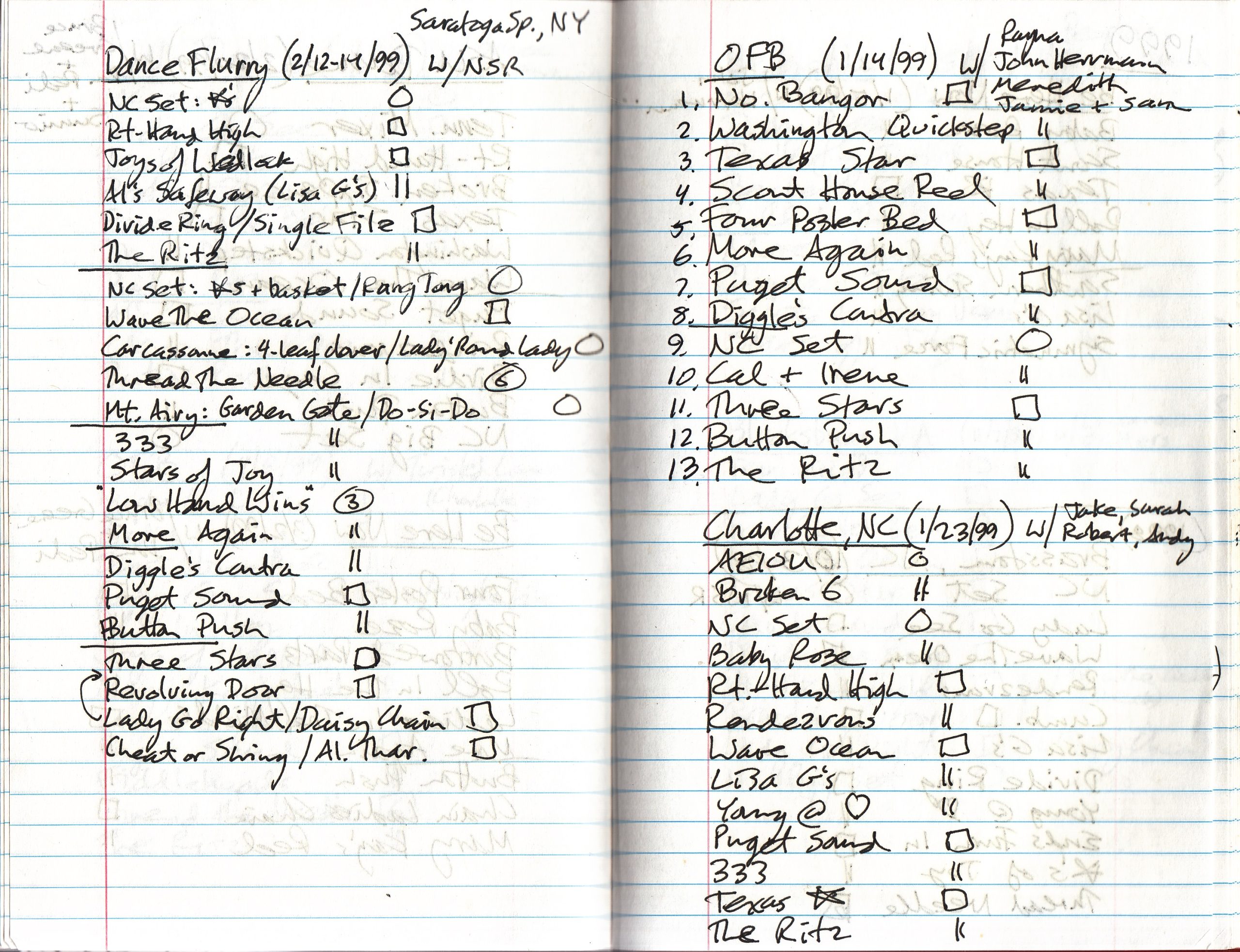

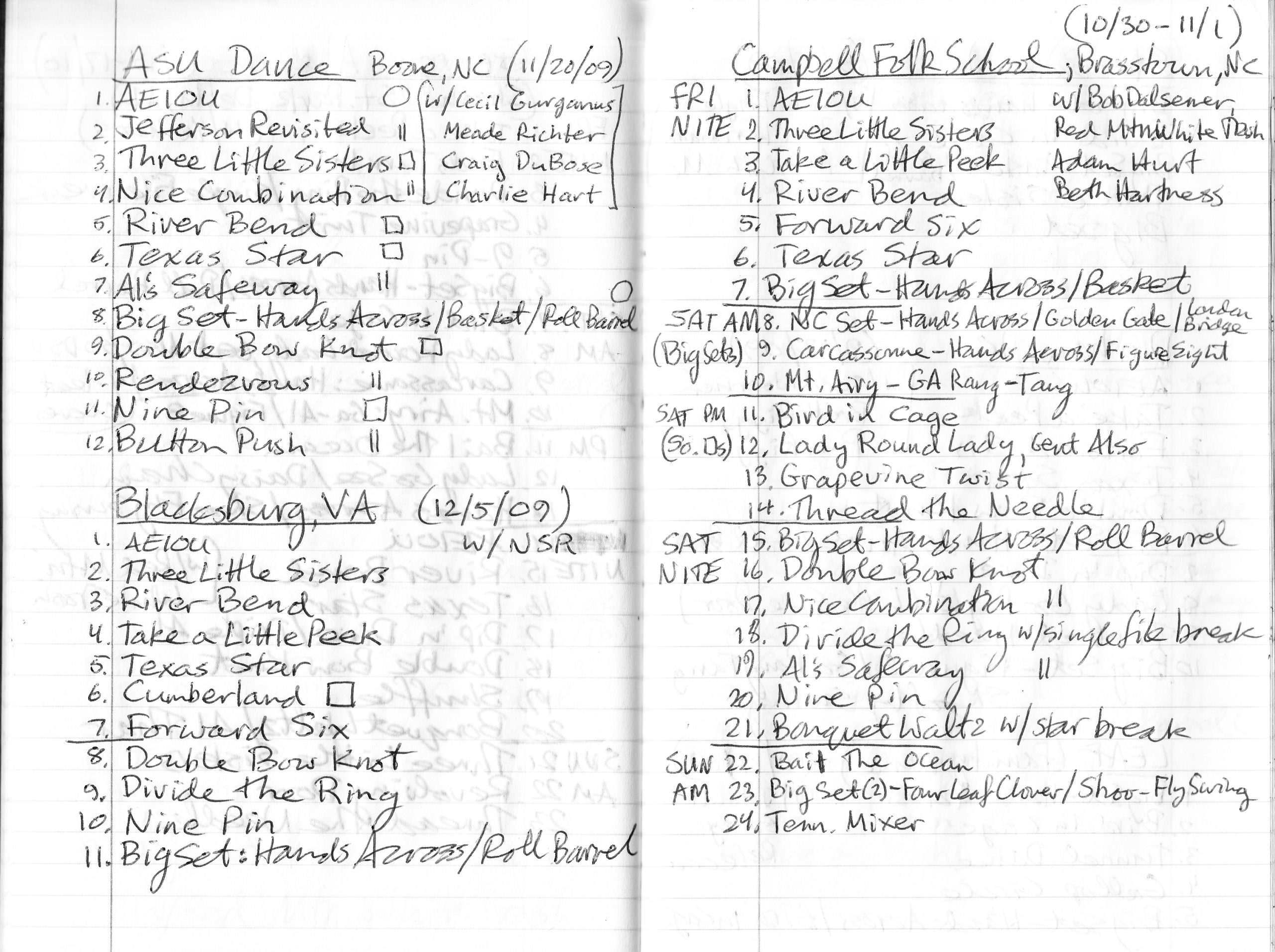

Phil shared photos of a few well worn dance cards (click to enlarge):

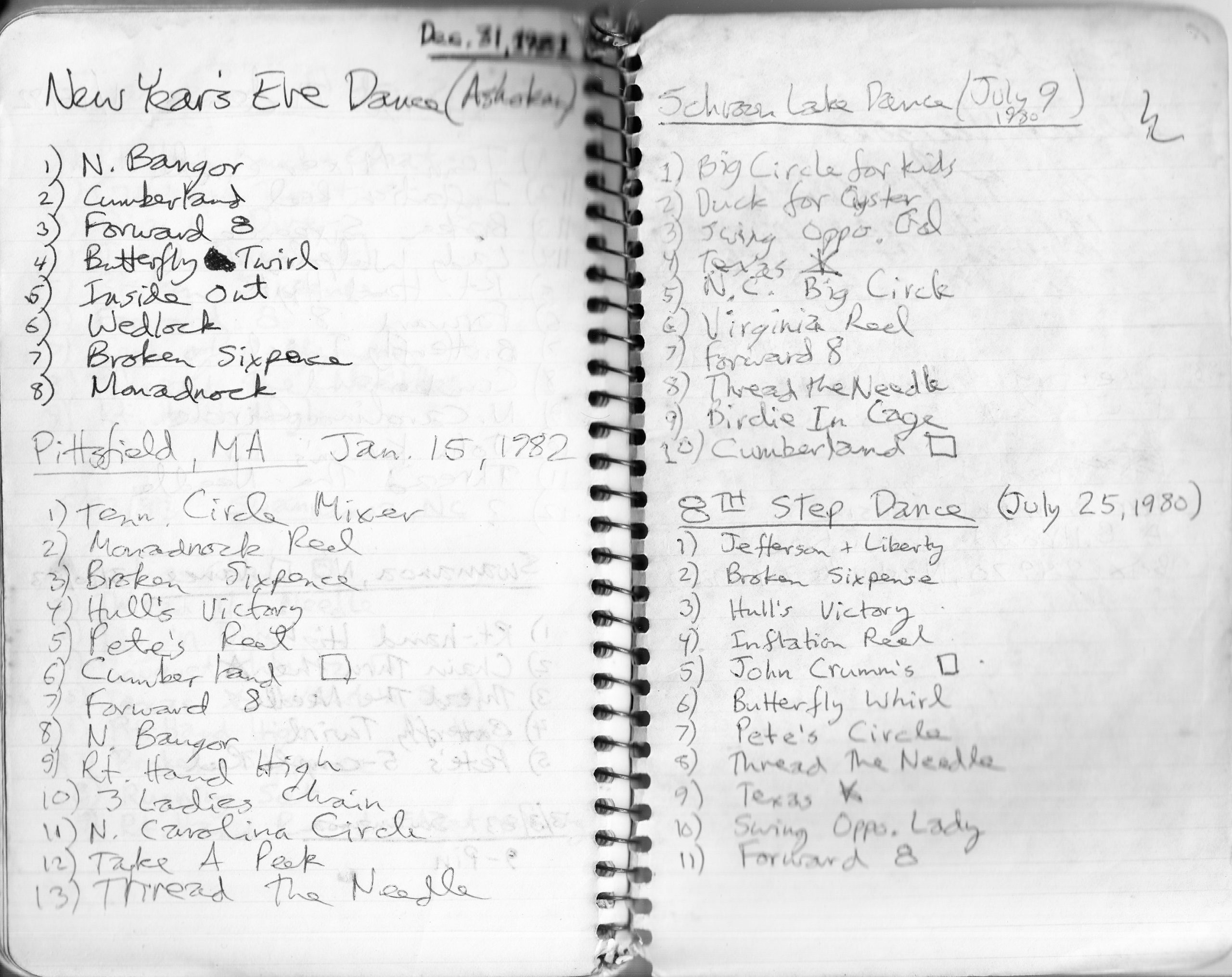

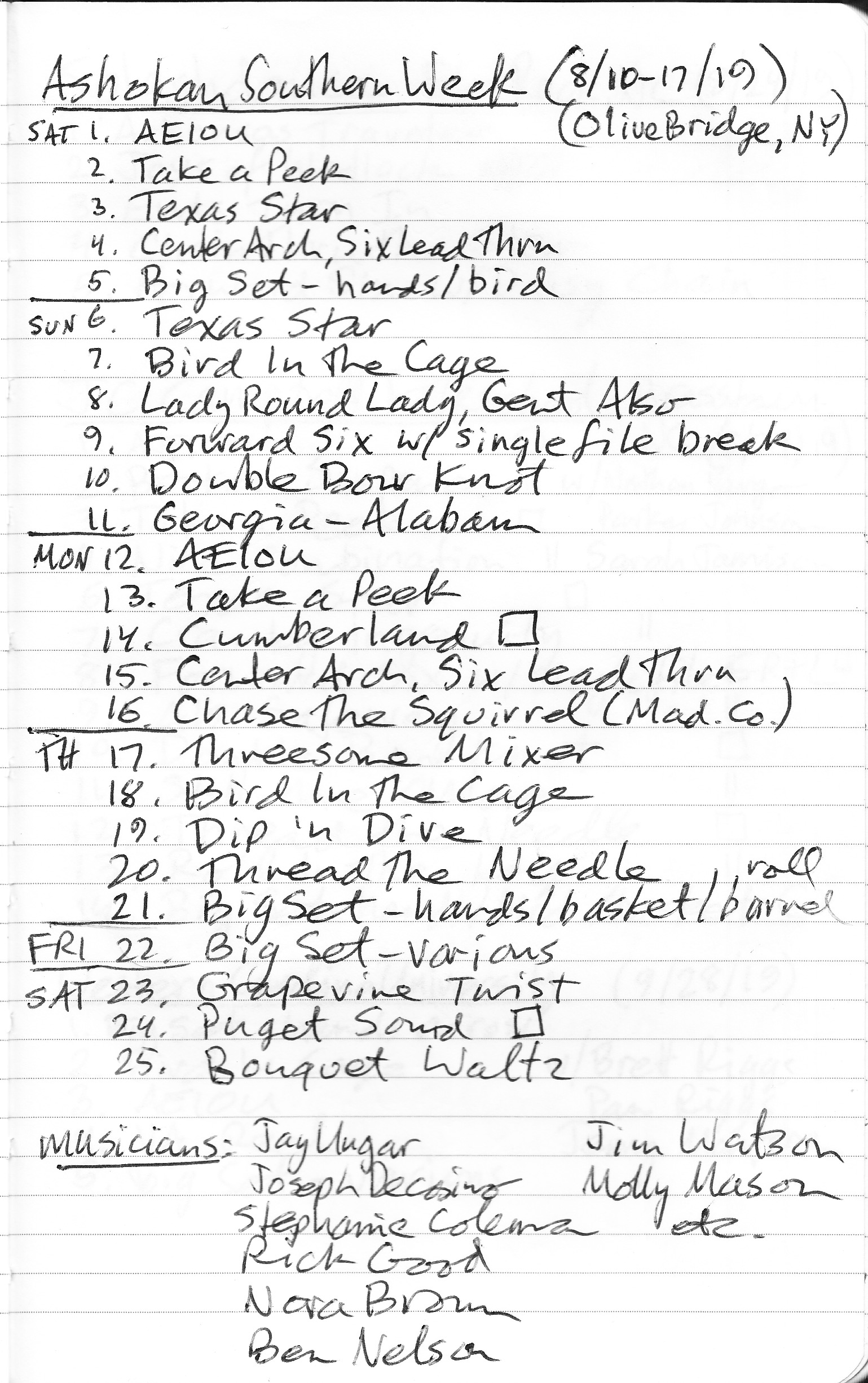

He has written down the set list of dances for every gig he’s ever called! He shared a selection from over the years (click to enlarge).

- 1980

- 1989

- 1993

- 1999

- 2009

- 2019

Episode Transcript

Click here to download transcript

From the Mic Episode 1 – Phil Jamison

Intro

Ben Williams: This podcast is produced by CDSS, the Country Dance and Song Society. CDSS provides programs and resources, like this podcast, that support people in building and sustaining vibrant communities through participatory dance, music, and song. Want to support this podcast and our other work? Visit cdss.org to donate or become a member today.

Mary Wesley: Hey there – I’m Mary Wesley and this is From the Mic – a podcast about North American social dance calling.

Through conversations with callers across the continent we’ll explore the world of square, contra, and community dance callers. Why do they do it? How did they learn? What is their role, on stage and off, in shaping our dance communities? What can they tell us about the corner of the dance world that they know, and love, the best?

Each episode we’ll talk to a different caller, but they all have something in common – a spark, a desire to lead, to share joy, to invite movement, to stand in that special place between the band and a room full of dancers (or people who don’t yet know that they’re dancers), and from the mic say “find a partner, let’s dance”

Phil Intro

Mary Wesley: There are hundreds of people I’d love to talk to for this project…it’s the kind of collection that will never be complete. To start us off I’m so pleased to share my conversation with Phil Jamison of Asheville, North Carolina.

Phil is nationally-known as a dance caller, flatfooter, and old-time musician. He plays fiddle, guitar, and banjo. Over the last thirty years he’s done extensive research in the area of Appalachian dance. His book Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance tells the story behind the square dances, step dances, reels, and other forms of dance practiced in southern Appalachia.

What especially caught my attention in Phil’s amazing research was his discussion of the history of dance calling. How the role of a caller diverged from the career “dancing masters” of the 19th century and how, particularly in the southern Appalachian region, callers played a vital role in perpetuating and sharing dance traditions, ultimately making dancing more accessible to a broader range of social groups. Phil has also worked to shed light on African American and Native American influences on southern Appalachian traditional music and dance.

In this episode we’ll hear more about this important work and we’ll also get to know Phil himself. He was kind enough to share some great audio clips of his calling and a few tracks from his many bands so you’ll get to know him through his music as well as his words. You can find the full information about everything you hear in the show notes at podcasts.cdss.org. Here’s Phil!

Intro/origins

Mary Wesley: Phil Jamison, welcome to From the Mic.

Phil Jamison: I’m happy to be here. I’m here in Asheville, North Carolina, speaking to you in Vermont.

Mary Wesley: That’s right. Yes. I’m surrounded by my blanket fort here, my home recording studio. Well, this podcast is exploring dance calling in many different ways and forms and sort of taking a caller-by-caller approach. So I wonder if you could start by just introducing yourself and talking about how you got started as a caller?

Phil Jamison: Before I was a caller, I was a musician and, you know, I had, I had gone to dances as a teenager. Like many people, I had experienced square dancing or endured square dancing in middle school with somebody with a record player. And I…as a teenager, I’d been to some contra dances in southern Vermont. So I was aware of the dance tradition, some of the dances. But I was a musician first and I was in…in college I started playing banjo and I was…I went to school in central New York state at Hamilton College, and just north of there in a little place called Barneveld there was a community that had, had a monthly dance, and I started, before long, start sitting in with people playing music there. And one night the caller wasn’t there and somebody had to call the dances and I gave it a try. I was relatively shy, but I thought, “Well, I’ll try it.” And it was very empowering. It was…I think it changed my life and gave me confidence to stand up in front of people and speak. And so I continued from there. I just, I never…I kind of fell into it just because this caller didn’t show up.

And so I started calling about, I think it was 1975. And at that time there weren’t so many contra dances in New York state. It seemed like there was kind of a dividing line between New York State and New England. So I’d say for the first almost five years, I was only calling squares. So my earliest dances I did learn from “Old Guy” callers, and I regret that I didn’t take names and details of who these people were. I was young and naive. I was just soaking it up. And then I discovered that there were books of square dances in libraries, you know, things that had been written in the 40s and 50s and I would go and I’d find dances that I might want to try and copy down the figures and add those to my repertoire. And along the way, I joined a band up in Potsdam, the St. Regis String Band that…and we would have a weekly dance at a little pub in Potsdam that people would come out to. Later on, the band started traveling more and we actually relocated to Saratoga, and at some point we got hired to play at the Chelsea House, which was a music venue in Brattleboro. And it was a two night thing. We did a concert one night, but the next night we were supposed to do a dance and I was told that we needed to include contra dances because we’d cross the line into Vermont. And so I ran to the library and I looked at a book and wrote down some simple contra dances and was able to call some contra dances. And that was sort of my introduction to calling contras. And then beyond that, you know this, this would have been, I think, 1979, as contras became more popular around outside of New England, I started calling more. And in 1980, I moved here to Asheville to join the Green Grass cloggers. And at first there wasn’t a local dance here. But in 1982, Fred Park called a bunch of us together and we started this dance called the Old Farmers Ball that took place at an old dance hall here in Swannanoa. And the dance hall had been built in the 1930s, had been a dance…built as a dance hall. And Fred got us together to do a dance and at first it wasn’t a contra dance, it was anything. You know it could be circles, could be squares, could becontras, you name it, and everybody was open to everything. And it really felt like a community dance where people would come together and even if you didn’t feel like dancing, people would come and hang out and hang out on the porch and drink beer or whatever and just socialize. So, and, but the dance grew over the years and got bigger and bigger and then relocated here to Warren Wilson College, where I teach, to the bigger dance hall. And over the years really became more of a contra dance than what it started out as. But as a caller, I would, you know, I was one of the few who, when I was at the Farmers Ball, would continue to call squares. And I would do a mix. I’d do maybe 50-50 contras and squares, but that’s one of the places where I first met up against this opposition to squares where I say, “OK, get your partner for square” and you get booed by the dancers, and that didn’t feel very good. So I became an advocate for squares early on. And as the contra dance world grew and grew, you know, I tried to maintain that and there were plenty of places where I could have called, but I was told they would have to be all contras, and I would say “No, thank you.” So that was, that probably meant a lot of dance…of the dance circuit I never got involved with, but I did get to do a number of dance weekends where I would, there might be a contra caller and I would be the square caller and we’d do a mix. But anyway, so I have a history of ‘squares versus contras’ that I have spoken about and written about.

Mary Wesley: So many questions! This is always the part in the interview where I’m like, “Which path do I go down here?” A few little things, so where…did you grow up in New York state?

Phil Jamison: Well it’s kind of complicated. I was born in Rochester. My dad was a professor there. And then as a kid, we moved to Lexington, Massachusetts, for my middle school, early high school years. And I actually finished out my last two years of high school at what is now Northfield Mount Hermon School. Back then it was Mount Hermon School, and then my family moved back over near Utica, New York, and then I lived in the Adirondacks.

Mary Wesley: So moving around a little bit. And did your…was there music or dancing in your family as you grew up? Or was it really in college that it came together?

Phil Jamison: Well…there was no music in my family other than on records, but you know, when I was about, I don’t know, eight, at the University of Rochester, my dad took me to a concert with Jean Ritchie and the New Lost City Ramblers, and I remember that distinctly. And we had records in the house of, you know, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie and other folk people. So I certainly heard music, heard traditional music. But no, my parents were not dancers, and nobody else in the family played music. But it really got a hold of me.

Finding the old time music scene

Mary Wesley: Yeah, I wonder if you can say a little bit more. So you said you were a musician kind of, first and then..I wonder how many callers stepped up to…you know, to save the night when a caller didn’t show up? I feel like that’s a certain origin story for many people. But if you broaden that out a little bit, how did you get into the music scene? What were you playing…

Phil Jamison: Yeah, so when I was 16, I worked at a camp in Massachusetts and there were kids playing guitars and frankly, I love the chords to the House of the Rising Sun and I said, “I got to learn how to play those chords,” and that’s what started me playing guitar. But when I when I got to college, when I was, I think I was 19, somebody had lent me a banjo and I’d always liked the sound of the banjo and had heard Pete Seeger and other people playing. And so I just basically in my dorm room, sat down and started learning how to play banjo. Somebody showed me the basic clawhammer thing and and then I, at the time I was working in the woods in the Adirondacks at Cranberry Lake, and I lived in a cabin with no electricity, all by myself, and I’d come home and just sit down and play banjo until bedtime every day.

But it was after college that I moved up to Potsdam and got involved with the St. Regis String Band. And that’s when I was much more involved playing for some dances and things. And I do remember one time in the late ’70s going over to Burlington for an all night, all night dance with the Arm and Hammer String Band. And at that time, Pete Sutherland was the caller with the Arm and Hammer String Band. So Pete Sutherland and I called the dances at the all night dance in Burlington. But one thing that stands out to me is that most of us, well I don’t know if it’s most or many, but a lot of us who learned to call—started calling in the ’70s—came from the ranks of the musicians. Many of us were musicians first and transitioned into being callers. And I find it really interesting, is that, my perception is that the newer callers, contra dance callers come from the ranks of the dancers rather than the musicians. And I find that that sort of means they’re coming from a different place. And I don’t know, I don’t quite understand what it all means, but I find it’s an interesting trend.

Mary Wesley: I’m really interested in checking that out as I talk to other callers> It’s a great thing to track here. Do you have any other memories or around kind of making that transition and how your perspective changed going from backing up or supporting the dance with music and then shaping the dance, leading the dance as a caller?

Phil Jamison: One one thing about being in the various old time bands that I’ve been in over the years is we’ve never been primarily dance bands. And I think there’s a really interesting thing is that, you know, the old time bands, at least of my era, you know, we would play coffeehouses and bars and dances. But we were not, we were not a dance, a contra dance band.

Mary Wesley: So how does dancing happen in the old time music scene?

Phil Jamison: So, yeah, so oftentimes there’ll be, you know, if there’s a jam and if there’s a wooden floor or a board to dance on, somebody will get up and do some flat footing or buck dance or clog dance steps and basically be the percussionist to the tunes, because, you know, we don’t have any percussion instruments, but the feet are the percussion instruments. And for me personally, some of my most favorite times of my life dancing have been late at night at a fiddlers convention down south dancing on a piece of plywood in the dark where nobody can see me.

[ Sounds of Phil and friends flatfooting at a nighttime jam at the Clifftop Festival, 2010 ]

And I’ll be right next to a jam, a good hot jam, going and just listening to the sounds of my feet as the rhythm to the music. To me, that is the most fun dancing of all. Way more than any kind of performance thing. Just, nobody’s watching you just…you’re just doing it through listening. And so yeah, dancers will get up and make a racket with their feet and, you know, basically beat out the rhythm with their feet and time to the music. But oftentimes, if there’s space in a room, people say, “Well, let’s do a square dance,” and clear out enough space in the room and say, one set, you know, four couples together and somebody call the figures from from, you know, one of the dancers, call it as you go. And that’s not uncommon, too. So, those kinds of things do happen. And as I said before the pandemic hit, there would be, I don’t know, I don’t know about almost every weekend…but oftentimes there’d be situations where somebody say, “Hey, I’m having a potluck, come on over,” and when there is a party, whatever, you know, like 20 fiddlers will show up! And the hallway will be crowded with instrument cases and everybody brings their instruments and you know, there might be a potluck and then people will, you know, run off to various rooms in the house and close the door and, and jam. And you’re not playing for a dance. You’re not even, in those situations, you’re, you’re just playing for each other. And I see the music as a conversation. When I sit down with other people to play, it’s a musical conversation. You’re, you’re communicating with each other without words. And a lot of the old time music scene is based around these kind of gatherings. That’s the main focus. And, sometimes the jams are big, with lots of people playing, and other times it’s knee-to-knee in a very small, tight circle where you can really hear each other really well. Those, to me, are the most fun, the most, the most moving to me.

Mary Wesley: Mm-Hmm. That image of, you know, a circle of musicians knee-to-knee is so evocative. And so it seems so far away right now.

Phil Jamison: And I think of it when I, when I play music, say one-on-one with somebody, it’s very much like a dance partner. You know, if you’re going to waltz with somebody, you want somebody who understands the same rhythmic movement that you have. Otherwise you’re constantly struggling and pushing and pulling with that other person. And when you find the perfect waltz partner or the perfect dance partner, whatever, whatever kind of dance…it feels really good. And the same with playing music with people. When you find somebody who just locks right into the same rhythm as you and you’re on the same page, it is so good and you have this dance partner or music partner. And when you do it with four or five people in a tight circle, it’s like having that kind of dance experience with all those people at the same time.

Mary Wesley: Miss it. Miss it so much.

Phil Jamison: One other aspect of the old time scene that I haven’t mentioned are the weekend events, whether they’re fiddlers conventions or festivals or whatever. That is a huge part of the scene. And at various times during the year, there…a fiddlers convention is basically a fiddle contest. And the biggest, you know, the ones that people go to most commonly are Mount Airy, North Carolina, and Galax, Virginia. In the summertime, every single weekend, probably from Memorial Day through Labor Day, you can go somewhere within a couple of hours or here and camp out for over a week for this and just play music day and night. And yes, there are dances on the weekend, square dances in the lodge for four nights and there’s contests…banjo and fiddle contests and string band contests and dance contests and all that and some workshops. People come from all over the country and overseas to this park, this campground in West Virginia, every summer for this. So these are, you know, kind of huge events that…I don’t know that there’s a comparable thing in the contra dance world unless you think of contra dance weekends, you know. Contra dance weekend yes, you can go every single weekend and go to a contra dance weekend. It’s the same kind of thing. But, but it’s…almost everybody attending is a musician. So, and many of them like to dance, too. So there will be dances, but it’s much more musician oriented than dancer oriented.

Mary Wesley: So where, what are the settings in which you more deliberately make square dancing happen, or some kind of group social dance? I love this description of this sort of organic eruption of, of, of dancing that is just happening, you know, at a jam or a party or something. But where are the spaces where dancing is sort of explicitly on the menu?

Phil Jamison: So we in the old time music scene have several times started up a weekly or monthly square dance, and it’s been at different places. And up until the pandemic, it was going pretty well at a local brew pub in Asheville on a monthly basis on a Friday night. And what was wonderful about it was, or one thing I loved about it personally is I could go and bring an instrument I could play…I could be…it was always a totally sit in band, you know, rotating band all night long. Maybe five callers show up. So there’s rotating calling, and so I could go and I could play, I could call, I could dance, I could go have a beer, hang out and chat with people. And it was definitely a gathering of the old time music community. And one thing that was nice about it is no, there was no admission and nobody got paid. And it was a wonderful place to go. It was not a commercial enterprise. And as a caller or as a musician, you didn’t feel like it was a gig because you could play a few or not. Or you could, you know, call a few or not, or just hang out and dance and visit with people. And that’s what was going on here before the pandemic, and I hope we can get it up and running again.

Mary Wesley: The biggest example of Phil organizing square dancing are the amazing “Dare to Be Square” weekends, which he helped get started locally in North Carolina.

Phil Jamison: Nancy Mamlin, and I started this here, here at Swannanoa in 2004 and it was a square dance weekend. No contras, just squares for callers, dancers and musicians and, it was a lot of fun. It was a chance to actually explore squares and take the deep dive. And we had workshops for callers and we did it here for three years and then people in Portland wanted to do it. So they borrowed the idea and did a Dare to be Square west. And since, since 2004, by my count, there have been 26 Dare to be Square weekends all over the country. Actually not in the middle of the country, on either coast, I should say. It’s time for one in New England, I think. But, but just a weekend just to take the deep dive and do all kinds of squares and, it was, these were very liberating. And there’s a lot of younger callers who’ve learned at these weekends and now are growing up calling squares, which really makes me happy that…I was afraid, you know, I was going be a dinosaur and the last one and squares were going to die out. But I think, I think people are doing them again now.

Mary Wesley: And what’s you know, what’s your calling life? I mean, of course, we have to acknowledge we’re in a very strange moment here. We had a long, prolonged moment of not very much dancing happening because of the pandemic, but you know, more in recent years. What does your calling life look like?

Phil Jamison: I would say, you know, before the pandemic, I would do maybe 20 dances a year, 20 some. And that’s not counting like wedding gigs or those kind of things. But, you know, real dances. And I can say that with confidence because since 1980, I’ve been keeping track of writing down every dance I’ve called in little notebooks. So I could, if you could say that, you know, if you want to say that you saw me at the Dance Flurry in whatever…1990, whatever or 2000, whatever, I could tell you exactly what dances I called there. So I’ve kept track of all my dances. And usually at the end of the year, I kind of count up, how many did I do this year? And it’s usually around 20. And I…I don’t take it, there’s a lot, I never was a professional caller going out and doing it, but…and like I say, as things turn more towards contras, it really limited the dances where I’d be welcome. So I would call if people want me, and if not, that’s fine.

Contras vs. Squares

Mary Wesley: Yeah, yeah, so I want to talk more about the sort of contra/square divide that you, that you experience. It sounds like you have had to…you’ve made choices about what your what kind of dancing you’re leading, promoting, making, making possible and I…yeah, I guess my question is how do you think about making choices about what you do and don’t do as a caller?

Phil Jamison: Something I’ve thought about a lot over the years is, as a caller, am I a dance leader? Or am I an employee? And those are two very different roles. And as an employee, I would do just what the customers want. I’d please…the customer is always right and if they want to do contras all night, that’s what I’m going to do. And I sort of refused to be that. But I feel that over the years there has been a sort of a transformation that I, in places where I’ve been of the difference from being at a community dance to being a dance community. You switch those two words around. And when I started calling, these felt like communities getting together and some people will be there who weren’t dancers who were just there to socialize. But other people were dancing, and it was, the dance was a function of the community. When the community came together. And I feel that the dance scene has evolved into being more of dance communities rather than community dances and by dance community, I mean, it’s a community of dancers. And if you’re not a dancer, you wouldn’t go to it. You wouldn’t be there. You’re not really, I guess you might be welcomed to try it, but…it’s not for you. And the role of the caller I see has changed in the same way. So in the earlier years, if I was at something that felt like a community dance and I’m there as part of the community and I’m facilitating things and coordinating getting…making things happen, that is that is the role. And it’s a little bit like at a wedding gig where you’re there as you know, to get…make the connection between the people who want to dance and the musicians. And not everybody in the wedding is going to dance. They’re all part of that little mini-community for that evening. But you’re there to sort of make it happen. And it’s very different than when I step into what is a dance community—a community of dancers. And then I start to feel like an employee that, you know, these are people who have expectations and they’re there to do what they can because they’re avid contra dancers. And I get that. And I get up and say, OK, folks, let’s do a square now. And that’s not what they wanted.

You know, I understand the evolution and the changes that have happened. But, and I’ve observed it and written about it and spoken about it. And, you know, I will continue to call squares. And part of the reason I love squares is that they are, you know, I think as a caller, they’re definitely more challenging. If I call a dance, whatever Bird in the Cage or whatever. You take ten callers and all ten callers, if they call Bird in the Cage, it’ll be their own choreography of that figure. It’s…there’s not a published dance called Bird in the Cage, so it’s much more of a folk art in that the, you know, the individual artist or caller puts it together the way they want—they see to do it—rather than just reading it out of a book. And and so I find much more creativity in in square calling. And and it’s it’s a whole different, it’s a whole different head for…as a caller, as a dancer and as a musician.

[ Clip of Phil calling Grapevine Twist, DTBS Syllabus 120 ]

Taking a public stance

Mary Wesley: So I did want to hear a little bit more, you know, as much as you want to share, about, how it’s felt to to really publicly take a stance in relation to this change of contra dancing proliferating. You compared it to kudzu, sort of invasive, beautiful but invasive species you know, that’s, that’s really profoundly changed the thing that’s really near and dear to you. And you’ve described being, you know…asking people to find a partner for a square dance and getting booed from from the floor. You know, these…like to me…and that’s, that’s happened to me in various forms, you know, being at the mic is a powerful and a vulnerable place, you know, so, how has that been for you?

Phil Jamison: Well, when I first wrote the article, the first Dare to be Square article, which I think was 1988 and I, you know, I sort of put it out there. It was published in the Old Time Herald, which, you know, was kind of addressed to the old time music community to begin with, it wasn’t really addressed to the contra dance world. But people read it and passed it around. And you know, I got, you know, people sort of coming back at me saying, “Oh, you’re all wrong and this is this, you know, you just don’t see it right,” or whatever. I did feel kind of blacklisted or whatever, in certain communities and…whereas before that time, like in the earlier in the 80s, I felt way more welcome to, if I was traveling from the Northeast down to North Carolina to calling a few dances along the way. But I just didn’t feel as welcome anymore in some of the contra dance scenes…and felt kind of not welcome. And I think people took it as kind of an attack. And I was really just kind of stating what I was seeing going on and, and I think I called it “contra mania,” kind of this growing, growing trend of contra dancers, dances that I was seeing going on. And, you know, and, and it just continued. So it didn’t, it didn’t abate at all.

Mary Wesley: I mean, at a certain point now, does it feel like contra dancing and square dancing…is it like comparing apples to oranges at this point?

Phil Jamison: I guess the question, yeah, I feel like the contra dance world has evolved to such a point where a lot of today’s contra dancers, that’s what they want to do, and why should I come in and throw a wrench in the gears of what they’re, what they’re loving and say, “No you should try this instead.” I don’t feel like I want to impose my views and history and taste on people who are loving what they’re doing. I find it sad that a lot of people are locked into just this one thing and closed off to something else. But that’s what people do. I get that.

Calling Philosophy

Mary Wesley: Hmm, yeah. Well, one of the things I’m hoping to explore through this podcast is really looking at this, this job of a dance caller. This thing that we do in different forms. You know I think it’ll be interesting to see how is calling a square dance different from calling a contra dance different from calling at a wedding or calling at community dance? I wonder if you could maybe put your, put your caller hat on a little bit and talk more about nuts and bolts or what’s involved in calling for you? So is there a way that you would describe your approach or calling philosophy? What’s important to you when you’re at the mic?

Phil Jamison: As as a caller, I feel like I’m the connection between the musicians and the dancers, and you’re the emcee, you’re sort of facilitator, you’re making it, making it all happen. And you know when I prepare to call a dance, I will usually at home before I go to the dance kind of ruffle through my dance cards and I will pick out a whole bunch of cards of dances that, yeah, I might like to do that one tonight or I haven’t done that one in a while, that might be fun. And I’ll up, I’ll pick out like twice as many dances as I would do in an evening. In a typical evening, I’ll do 12 or 13 dances. So I’ll pick out twice that many cards and some of the some of the dances will be squares, some will be contras, some will be easy, some will be hard, some will have certain elements that might be fun, but and I’ll always try to include something that maybe I’ve never called before or that maybe I’ve only called once and I’d love to try again something like that. So I take all those cards and I put them in my back pocket. And I usually start, I like to start a dance with something that everybody can join in, something easy. Sometimes it’s a big circle mixer or a or a simple contra or a simple square. I basically start with simple dances and I look at the crowd and watch how they’re doing and see what their skill level is and see if I can ratchet up or need to back off, depending on what’s going on out on the floor. So sometimes a little…I may be over optimistic about their ability, and sometimes I underestimate them.

And any time I finish a dance, I’ll stick the card on the bottom of my pile in my back pocket. So at the end of the evening, when I go home, I have all the dances in order in my back pocket, and the next day I can copy them down in my little book and keep a record of what I did. You know, so and I’ll look out at the floor and I’ll see, Oh, are there kids dancing with their moms? Are there, you know, are there certain issues that I might want to be thinking about in terms of my dance and the terminology I’m using in my, you know, as far as gender free calls, perhaps? I’ll think about those things. When I call a square, one thing I do, which may sound really weird, is I will say, you know, “Get your partner, next dance is a square, get your partner for a square.” And I have no idea what the next dance is going to be. Zero. And I will look and see what I have to work with out there, and I will pick the dance depending on who’s squared up out on the floor. And, and so that’s why I have multiple cards in my pocket to, oh this, this will work for this group or this one wouldn’t work for this particular lineup. And it may sound weird, but you know, as they get squared up, I have no idea what the next dance is going to be. But I try to keep that flexibility to, to be able to deal with whatever group of dancers we have. I try to build somewhat on, during the evening, build on figures that I might have done. If I teach a certain figure in a dance early on, I might try to incorporate that in another dance later in the evening once people have learned it. And I will probably increase in the level of difficulty until about three quarters of the way through the dance. And then in the last couple of dances, I just like to do brain dead simple dances that anybody can just do. You don’t have to…you quit thinking, just dance. And if there’s a contra dance with only your partner swing, that’s…I would do that later in the evening like that. And I usually like to end the evening with something that everybody can be in on. So I often would not do a four couple square because you might have leftover couples. So I would either do a contra or a southern big circle set that everybody can be in on to kind of end the evening with everybody, everybody together. So those are some of the things that I think about when I, when I call.

Mary Wesley: And how much of that…that’s great, it’s such a clear arc. What you’re describing is very…sounds very responsive to the crowd or the hall. And how much of that connects to this idea of a community dance or sort of a community experience for the dancers, for you?

Phil Jamison: Well, it’s both. There’s no way that I could come up…I couldn’t…I couldn’t tell you what dances I’m going to call that night until I get there, or until it actually happens. So, but I I do like to create the sense, you know, add to the sense of community with the dancers so that it’s not just a bunch of individual dances, but there’s some kind of storyline and getting people together and ending the evening all together. And that’s something that I love about dances. You know, even if it’s just a, whatever, “one night stand” or dance at a wedding or something, you’re building something; creating bonds between people. And I think that’s a lot of what I love about calling.

Mary Wesley: Yeah, so, so calling squares…[the] square dance caller is is way more involved in shaping that experience for the dancers, providing those surges of energy or you’re just you’re just more hands on because you’re you’re in some ways constructing the dance in the moment. Much more on the fly experience.

Phil Jamison: Right, with a contra dance, I can go out and grab a beer and I can keep on dancing and….I’ve never left a dance completely, and I’ve always come back.

Mary Wesley: That’s nice, that’s nice of you. So how do you…how do you do that? I mean, that is a real art. As a caller calling on the fly, you’re not, you’re free from from structure in some ways, you might have a figure that you’re returning to or something, but there’s just, there’s really this…you were talking about this higher level of kind of creativity as a caller, how does that process work for you?

Phil Jamison: One thing I’m fascinated with is the idea that people see you up there as a caller…and with squares, people might think that they’re following your calls, but in fact, my calls are following the dancers and I watch the dancers, and when they’re ready for the next thing, I give it to them. You know, if the dancers are moving slow, the calls will come a little bit later. If the dancers are quicker getting there, the calls will be a little bit sooner. And it’s the dancers that are setting the pace. If you have different sets on the floor like a bunch of different squares, there are a couple of things I would use to sort of even things up. If there’s a slow group here in a fast group there I can put on a “swing your partner” and that’s indeterminate length. So I would say “swing your partner,” and once I see everybody swinging, then I’ll go on to the next thing. And some people swing longer than others, that’s fine. You could say “join hands with circle left.” Some circles will turn more round than others. But once you see everybody circling, everybody’s back on the same page. And, you know, that’s part of why I see it much more of a craft, and it’s much more calling…I’ve often talked about the difference between calling and prompting. In a contra dance you’re basically prompting people, reminding them what to do next and calling is much more interactive.

[ Clip of Phil calling a big set dance – DTBS syllabus #143 ]

Gender Free calling

Mary Wesley: I circled back to ask Phil more about using gender free calls. This is a big consideration for contemporary callers and dance leaders and something I’ll ask about in most interviews for this podcast.

Phil Jamison: So, one thing I find challenging as an older guy, dance caller who’s been at it for so long is the idea of transitioning to gender free calling, or gender…or gender neutral? You know, I am aware of the “Larks and Robins” terminology that people are using at contra dances. And I have had people ask me to do that with squares, too. With squares, because of the interactive nature of it and with patter calling, it would be so much harder to do. And so for example, if I usd the figure, you know, “lady round the lady and the gent also, lady around the gent and the gent don’t go.” OK, let me see “Lark around the robin and the, and the robin don’t…” You know, it’s like, I’m getting confused. How are the dancers going to figure it out? So if I’m in a situation where it needs to be gender free calling, I won’t do that dance. I have plenty of other dancers in my repertoire that I can do that don’t have any reference to ladies or gents. But, it would make me sad to sort of throw out all the, you know, some really wonderful dances that do have that terminology that, I feel like the positional terminology is important. And I know people have used “rights and lefts,” but we use right and left for hands and circles. And I’ve seen it, I’ve seen people try that and it just seems really complicated. So I’m not sure what the answer is on that as far as squares. And, you know, unless to think of ladies and gents just as historical labels. And it doesn’t mean you are a lady or are a gent, anybody can dance either position but these are the, these are how I’m going to identify you. That’s the only way I can think about doing it, but I totally get it. But it’s something I’m still trying to wrap my head around.

Mary Wesley: Yeah, I think for me, it really, it really straddles this line between dance caller as employee dance caller as, as sort of leader or community leader because it can, it can really be at play in either one of those situations. I mean, sometimes. I’m hired for a dance weekend and the people who have organized and shape that dance weekend say this is the terminology we’ve used, and if I want to be hired for that and participate, then I’m going to follow suite.

Phil Jamison: And I would do that too. If that was if that was put out and saying, this is what it is, and I would think to myself, “Well, this will be a challenge, let me think what squares can I do that will do that?” I don’t think I would go to larks and larks and robins for squares, but there’s plenty of squares I could call without…it just means that some other really cool ones that I would love to share that will be ineligible.

Mary Wesley: Right. Right, and then I think the flip side from this sort of community standpoint is if I’m, you know, if I am calling for a roomful of beginners particularly, I don’t know if you feel this way with college students, but often when I’m in in a setting with young people or just thinking about anybody coming in off the street to try this new thing…If one of those people happens to be someone who’s really struggled with their gender identity and has sort of trauma attached to traditional gendered language, then I have to be aware that there’s the potential for, you know, for harm or for kind of creating a barrier for that person joining in. So, you know, and I think the way that you present it is really is…that the caller presents it is really important to sort of explain, you know, roles. Explain that, yes, for, for…to explain and teach the figures, you need to be able to differentiate and have a way to let people know who you’re talking to and how to direct them. It’s really complex. Do you know of anyone who’s, who’s sort of trying to write new patter to to incorporate terms like larks and robins?

Phil Jamison: Not with patter calling. You know, if it was, if it was like a quadrille or a New England square that’s all choreographed to the music, you know, that has a ladies chain and a right-left through and those kind of things sure, you could do that, but I don’t, I don’t know how… You know, and yes, as a caller, I could probably figure out how to do it, but I think it would confuse a lot of dancers. Especially, you know, when you know, if it’s a contra dance community of “professional contra dancers” who all know, know the whole scene and know everything, they can certainly handle it. But when you have people coming in off the street and wanting to join in or at a community dance where everybody is not a total, you know, up to speed dancer. I’m not sure how easy that will be.

Mary Wesley: Yeah it’s so interesting to think about because I hear this, you know, this connection to these historic figures and calls that have been used for a long time. And there’s also I think you know this is a folk tradition. There’s this opportunity for, um, for innovation while referencing some roots or some, hopefully keeping some continuity in the form. So I’m curious to see where it goes.

Phil Jamison: You know, as a musician, there are plenty of songs in the old time music repertoire that come right out of blackface minstrelsy and people are generally shying away from those tunes now. There’s some wonderful, wonderful music, but people aren’t playing it anymore because of the connotations. And it could be the same with the dances. Maybe I will just chuck out all the dances that use that terminology and stick with dances that are neutral. I mean, a part of me that makes me sad because you’re losing some really nice choreography, but I don’t know. I mean, these are folk traditions, and they do continually change so I, you know, even you know, talking about changes in terminology, even contra dancing, you know, 40 years ago, people would refer to people as “active” and “inactive.” We don’t do that anymore. Those words have gone by the wayside. So, you know, I can see in, as I say, in contra dances it’s a whole lot easier. In, in squares, yes, things change and if certain terminology makes people uncomfortable, that can be avoided. It’s an issue that I’m sensitive to. I’m aware of and I, you know, I do my best in a given situation.

Debate Everything

Mary Wesley: I appreciate Phil talking about this with me. There’s a lot of dialogue about gender free terminology in dancing right now. It’s a really important topic and just one example of how traditional art forms shift and change over time…how they’re influenced by larger social contexts.

On this podcast I hope to make space for callers to share their experiences, thoughts and ideas about changes they’ve witnessed and changes that are happening right now in the dance forms they practice and care about.

Change is a process. Often a messy one, which is why I think it’s all the more important to listen deeply to one another as we muddle through it.

In his book Calling for Beginners by Beginners, David Kaynor writes:

“Every human process stands a better chance of thriving and evolving if debate…is genuinely and energetically embraced as an agent of clarification and evolution. Any process from which debate is excluded is likely to wither, shrivel up, and disappear.”

So friends…let’s keep debating, discussing, listening, questioning, and DANCING!

Phil’s Research

Mary Wesley: So I’d like to talk about your book Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance. And how did you come to write this book?

Phil Jamison: Well, the book was the result of trying to understand the history behind…specifically, it started out with the square dances that Cecil Sharp had documented and talked about as being old English and that just didn’t seem to be the full case, you know, I felt there was more to the story. Actually, in 2001, I went to an Appalachian Studies conference in West Virginia and at the conference there was somebody there from the University of Illinois Press, and I said, “I’m looking for, do you have any books on Appalachian dance?” And she, the woman there, said, “No, why don’t you write it?” And this is in 2001, I thought, “Oh my gosh,” well, I’d written articles for the Old Time Herald, but I never really thought about writing a book. That’s what got me going on it. And then subsequently, I enrolled in the Appalachian Studies Program at Appalachian State and made dance my focus throughout that whole program, and that really got me started on this.

Mary Wesley: So I’m wondering if you can fill us in a little bit, or kind of tell us in broad strokes how the role of the caller developed in relation to these dance traditions over time?

Phil Jamison: When I was researching these dances, I was really curious about where dance calling came from. And I started looking for the earliest references and the earliest really clear cut reference to a dance caller is 1819 in New Orleans and it was a black musician calling out the figures of a quadrille. And the person who was documenting this, a guy, Benjamin Latrobe, (who was actually the architect who designed the U.S. Capitol), he was an English guy, and he was writing in his journal and saying, “Oh, this is a weird thing. I’m not used to seeing this.” But he was sort of dismissing it as kind of a vile practice. But that was the earliest, 1819. And then I found other references from the 1820s of, again, black musicians calling out dance figures in South Carolina, in New York state and Massachusetts. And, I started to see them lots of other places. And one thing I discovered is that “back in the day,” as we like to say sometimes, is the people who provided the music for public dances were black. And playing the music for a dance was a servant’s position, whether you were enslaved or a free black, it was a servant’s position. And you know, many of the early fiddlers at these dances were black. There were enslaved Africans playing for white people’s dances in Virginia as early as 1690. And throughout the 1700s and 1800s, if it was a public dance, chances are the music was black. And there were certainly white fiddlers around but it was more like, what I was finding was, white fiddlers play for family and friends or small gatherings. But if it was a bigger event where you’re inviting people over, just like today, if you’re having a wedding, you’re not going to do the cooking yourself, you’re going to hire a caterer. Similar kind of idea, you’d line up a black fiddler. And for African-Americans, it was a…it puts you in a better place in life. And there was a fiddling tradition in Africa going back to the 12th century. And in this country, if people of African descent adopted the European fiddle and played those, the tunes people want to hear, you wouldn’t be out working in the fields, but you’d be playing for the dances. And that was, it was a much better place and there were enslaved people who bought their freedom from the proceeds they made for playing for dances on the side. It was a powerful thing and there were dancing masters who owned slave fiddlers to provide music for dancing school and references to dance calling are really rare. Dancing masters would prompt the figures at dancing schools and in the European tradition, there’s no history that I can find of dance calling or even prompting at a public dance. But when quadrilles came in, these were more complicated dances and it seemed, what appears is that black musicians started calling out the figures for white dancers and made it easier. Now when quadrilles showed up here is hard to say because some people, some of the early references to quadrilles actually could have been cotillions, but I’m not sure, but it seems like, you know, around 1790s early 1800s is when these dances were showing up. And certainly, the dances were more, maybe too complicated to memorize at dancing school, and a prompt from a caller would have been a welcome thing for the dancers. And even in England by the 1820s, these quadrilles were being prompted over there too.

But I found suggestions of dance calling even before the American Revolution. Somebody in Virginia in the 1760s talked about chanting to the sound of the fiddle at dances, and in the African tradition, there’s a lot of call-and-response and vocalization with music and another reference of enslaved people dancing English country dances in the 1770s in South Carolina. You know, those people weren’t sent to dancing school. Having somebody to prompt would have helped. And, so I think by the early 1800s, there were certainly…in the black community, prompting the dances made the dances accessible to black dancers. And a lot of the black dancers were doing the same dances as the white dancers, but not at the same place. White folks went to dancing school, learned the dances. Black folks could rely on the calling. So that’s what I think happened. And over time, it just…when the quadrilles came in, it made it more, it was more prevalent at white dances, too. And by the late 1830s, I find references to white callers learning to call out figures, too. And it basically put the dancing masters out of business. People didn’t have to go to a dancing school anymore. It also meant you could take components from lots of different dances and put them together and made the dances much more improvisational. And when people moved west, they could take the dances with them, you didn’t have to have a dancing master. You could just call out the figures. So that’s sort of in a nutshell about what I think of the development of the dance calling.

Mary Wesley: Yeah, I’m really interested in the kind of, would you say it’s like a democratization…?

Phil Jamison: Yeah, that’s a word that I’ve used. I mean, it used to be that the dancing masters would devise cotillions and country dances and quadrilles and you go to dancing school to learn those things. And now it’s one of the musicians calling out the dance figures and being improvisational. And you could add a dance figure from this tradition or that tradition, and you can make it your own. And it meant that the dances became a folk art rather than a written composition.

Mary Wesley: In one of your later chapters, you say “Dance calling is without a doubt the single most important factor in the creation of these American folk dances. They would not exist without it.” Can you say a little bit more about that?

Phil Jamison: Yeah, and in my book, I’m specifically writing about the southern Appalachian dances. I’m not talking about northern quadrilles, which again were composed dances and, you know, two A parts, two B parts and written down on paper. But the southern, the southern square dance is very much an unwritten, oral tradition. And yes, eventually, you know, by the 20th century, people started…or Cecil Sharp came through in the teens and went to Kentucky and wrote down dance figures. But before that, nobody was writing this stuff down. It was just being passed along from one person to another. And it was really the dance calling that that could make it all happen because it wasn’t, it wasn’t…this was not a written tradition.

Mary Wesley: You also talk a lot about the ways that southern Appalachian dance is American. I think you’re citing someone else in the book with the phrase “uniquely American” comes up and I’m just thinking about, you know, I feel like even as I have come up and you know, learned contra dancing, but also square dancing more, I grew up in New England, so that’s a bit more my background. But really often I would hear, you know, contra dancing or even square dancing is a descendant of European dances. What’s your response to that?

Phil Jamison: Right, well, it’s again, I’m writing mostly about the southern dances. So, yes, New England contra dancers are descended from English country dances, and the squares of New England are descended from the French quadrilles and cotillion. So, but what I’m mainly looking at is the southern traditions. And yes, people look at these dances and say “Oh, this, you know, those Scots Irish people came down the Great Wagon Road and settled up in the hills and hollers and played their fiddles and had their square dances and clogging and such and now we have square dances. But there’s so much more to it than that. The people, the Scots-Irish people who came south, they were not dancing square dances. They were dancing reels, which were generally for like two couples in a small, confined space. Not a complicated dance. Lot of hand turning kind of stuff. And people danced in their homes and taverns. There were not big dance halls. So there were, and there were Native American dances that were generally in a circular form and some of the Native American communities, they would do those dances, but they’d also learn the dances from the European people. So things got mixed up very early on, and same in the black community. People were swapping these dances back and forth, learning from each other, sharing figures. And when the French cotillions and quadrilles came in, then you get the square form, whereas earlier it might have been more, either two couples or expanded to a bigger circle. But when the quarilles came in you got a square form and you get the grand right and left and promenade. So you have French dance figures, you have Scots Irish figures. Contra dances were not generally known in this region, though I believe that the figure “chase the rabbit, chase the squirrel” may be inspired by “Hunt the Squirrel,” which was a Playford dance. And, and I believe that “Bird in the Cage” descends from an African dance. So you have all these different elements coming together to create these American dances. And you can’t say that these are English dances. You can’t say they’re French dances. You can’t say they’re African or Native American, but they are a combination of all those elements. And that is, you know, what makes them American. And you know, people, you know, you talk about the melting pot of all these different cultures coming together to create something new. And, and that’s really what these dances are. And so that’s why I would say they are uniquely American, that they have all these different elements that come into it. You know, when you think about any other type of “American” music or dance, what do you think of? You know, whether it’s jazz or blues or rock and roll or tap dance or swing or, you know, any other kind of bluegrass, any kind of “American” forms, they all have black influence. So it’s kind of ridiculous or naive to think that, you know, the southern square dances don’t have black influence. Of course they do, just like the music does. I mean, the banjo was descended from an African instrument and, and the southern fiddling styles were heavily influenced by the black fiddlers. And I see the black influence much more in the southern tradition than in the north. There were black fiddlers in New England, too, but they don’t seem to have had as much an influence on the tradition.

Mary Wesley: Yeah, it’s it’s such important work it strikes me that you’ve done to kind of research and bring to the forefront these contributions of, you know, non-European communities and culture groups contributing to these things. Because I think, you know, there’s been lots of times in the past and still in the present day when you could still say something is “American,” but that would be put on as a label that could still really erase those contributions of black people or Native American people. Seems like there’s some places where “American” is still equated with sort of, people of European descent.

Phil Jamison: Yeah, and, and there were enslaved Africans here the year before the pilgrims landed. So, you know, and I mean, to deny that there is African American influence on…or African influence on American culture is just nonsensical. Of course, of course, there’s influence in lots of areas, but this is just one of them.

Square Dance Recordings

Mary Wesley: You reference a lot of recordings of square dance callers in your book and in your research. Can you tell us a little bit more about that?

Phil Jamison: Yeah. Back in the 1920s, when record companies started to record southern music on 78 RPM records, a lot of the records that were made of southern bands included dance calls. And the callers were not…these weren’t so much records you could dance to. They were just being done in a studio and, and they’d have a caller to call out dance figures, basically to add color to the records. And sort of, the calls were part of the music. And I got fascinated by these 78s with dance calls. And for most fiddlers learning the fiddle tunes, the dance calls are just an annoyance because you can’t hear the tune because somebody’s shouting out. But for me, they’re really interesting. So I started collecting them and they were done in the north, too. I have have recordings of contra dance callers from the 1920s too. But I was specifically looking ones from the southeast and I collected, I think, 95 of these and transcribed all the calls that I could decipher and mapped them out across the southeast, county by county, trying to figure out if there are any patterns. What dance figures were known in different sections in the Ohio Valley, as opposed to Virginia. Up in West Virginia, as opposed to further south. Were there differences in the dances and the dance calling? And these recordings are interesting, well, for a number of reasons, but one is that they’re kind of like snapshots of dance repertoire at that time and these dance callers who recorded in the 20s, most of them are clearly experienced dance callers. The words just flow out of their mouths. They’re, they sound like real callers. And they would have learned calling before there was such a thing as a recording. So they had not heard any other callers except live. So, people traveled some, so you could go to another community or another state and hear somebody else calling. But I think the regional differences are quite striking in these. So it wasn’t like somebody from Kentucky listening to a dance caller from Alabama and learning their style and dances. But you really get a sense of, what were Kentucky dances like and repertoire at that time? For me as a dance caller I think they’re fascinating because it gave me ideas for some dances and dance figures to add to my repertoire. It gave me ideas for patter, some rhymes and rhythm of how to deliver calls. And so in a way, these…all these dance callers on these 95 recordings were like my mentors in a way, you know, people who I’ve never met, but I’m pretty familiar with the way they called. And a few years ago, I had a sabbatical project, and what I did was I had all these recordings digitized. And I put them on a web site, so they’re all available. With the transcriptions so anybody can go and listen to these recordings and keep in mind, they’re not intended for dancing. A few of them you could dance to, but the timing might be a little off. It was later in the 1940s that they started putting out records you could actually dance to. But these were not intended. Just the…the calling is just part of the music.

Mary Wesley: Can we listen to some of these recordings?

Phil Jamison: Yeah. I thought we would first listen to, I mentioned the New England tradition. There was a fiddler from Maine called Mellie Dunham. Are you familiar with that name?

Mary Wesley: I have heard that name.

Phil Jamison: OK, well, he recorded, this is a recording from 1926 of the Chorus Jig, and let’s see if this will come through, OK.

[Mellie Dunham calls Chorus Jig]

Phil Jamison: So the calls are very much time to the phrasing of the music. And I would say those are prompts rather than calls because he’s just giving short commands about what to do in each case, and you know, and that’s what’s done in a contra dance. A few years earlier, in 1924, Samantha Bumgarner here in western North Carolina traveled to New York and made some dance call recordings of her playing banjo and calling southern big circle square dances. And the first recording, the one recording here is “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss.” A lot of people might know that banjo tune, but if you listen to her calls, here she is again kind of shouting it out. But it’s not phrased to the music like that Chorus Jig.

[Samantha Bumgarner calls “Fly Around My Pretty Little Miss”]

Phil Jamison: And so on. I’s not phrased to the music. She’s shouting out commands while she’s playing the banjo. And that was actually the first recording ever of a five string banjo. This woman, Samantha Bumgarner. First five string banjo recording. So I’ll play one other here of a caller named Ernest Legge from West Virginia. And he recorded in 1928 with the Kessinger brothers, and he has a very colorful way of delivering patter calls that I love. And if you were going to prompt it, basically what it would be would be circle left; allemande left; grand right and left; promenade. OK, you could do that with those four, four things. And let’s listen to how he does it with the tune Devil’s Dream.

[Ernest Legge calls]

Phil Jamison: “Chew your tobacco, rub your snuff, meet your honey, and strut your stuff.”

Mary Wesley: Oh yeah, I say that all the time.

Phil Jamison: Yeah! So otherwise known as “Promenade.” Well, so all that verbal diarrhea that you just heard there could have been said just with prompts: “Circle left; allemande left; grand right and left; promenade.” But it’s totally different. So, you know, that is a clear example of the difference between prompting and calling.

Mary Wesley: Why, so why? Why, why does he do it?

Phil Jamison: Why does he do it? Well, it is the tradition. It’s fun. The dancers enjoy it when you come up with ridiculous rhymes. And it’s part of the music, as I said. So it’s…the southern calling really is part of the music. And what I see is, you know, the big differences between just prompting and calling, you know, prompting is basically giving a reminder, reminding the dancers of what’s what they need to do next. And like I say, like, like in a theater, a prompter reminds you if you forget your lines, you know? But it’s meant to be short and concise. Just a quick reminder. And in this case, you have, with calling it can be much more improvisational. The caller can put out all kinds of different things. It can be, you know, typically using freeform timing, it’s not phrased to the A parts and B parts of the music. You’re much freer to do whatever you want. With the patter you’re, you’re putting in rhymes in there and pitching your voice often to the music. So, those are all things that I think came from the influence of the African tradition on these traditions. I don’t see those as European things. Fiddlers in Europe and the British Isles don’t sing along with their fiddling while they’re playing. But in Africa, they do.

[Ernest Legg calls]

Closing

Mary Wesley: To close, two just short questions that I’m a little curious from everybody that I’m going to talk to. You’ve already alluded to this, but how do you keep your dances? Do you keep them on cards or on a computer or something else?

Phil Jamison: So I keep my dances on little index cards and I carry those in a little case with me. And then at one point…I remember years ago being terrified, what if I lose it? So back in the old days, I would photocopy all my dance cards. But I got to the point where I’ve put them, typed them out on the computer and was actually able, when I had the previous printer I was actually able to just print on the index cards. So, if I was at a dance and somebody said, I like that dance, can I copy it down? I could just give them the card and print a new one at home. But yeah, I put them all on computer. But with southern squares, somebody else looking at that card couldn’t call the dance because the notes are very, very sketchy as far as the whole whole thing. So it’s for contra, yeah, I could hand someone my contra dance card and they could call it right off the card, but it’s not quite the same with squares.

Mary Wesley: Mm hmm. Do you have a sentimental attachment to those cards or anything? Does it feel like a…

Phil Jamison: Oh yeah, some are pretty dog eared.

Mary Wesley: Yeah. And then last question, do you have any like pre- or post- gig rituals or kind of things that you do to to transition in and out of your, your caller’s role?

Phil Jamison: Yeah, before I go to a dance, I always need a little bit of quiet time by myself to kind of look through my dances and think about what I might want to do that night. I have to confess sometimes it’s while I’m driving! Sorting through my dance cards while one hand on the wheel. But more often trying to find a quiet time at home before I head out, just to get a sense for, you know…OK, maybe I haven’t called the dance in a couple of weeks or a month, but what would be fun to do tonight? So I’ll usually do that. And sometimes I have a cup of coffee, but I find that I get energized from calling a dance, and even if I’m feeling tired before a dance at the end of a dance, I’m energized and I can’t just go right home to bed, so I usually stay up for a while afterwards. But I feel I get a lot of energy back from the dancers.

Mary Wesley: Absolutely, I know I miss that. I thought of one more short question, if you know: do you identify as an introvert or an extrovert?

Phil Jamison: Oh, I’m an introvert. Definitely. And it was dance calling, that time when the caller didn’t show up and somebody had to call, that’s what opened it up for me. And the idea of standing up in front of a microphone and telling a crowd of people what to do, that was not me when I was a teenager. No way. But there’s something I find fascinating about dance calling is that you’re given the microphone and as long as you know what you…if you know what you want to do. Everybody’s ready to do it. You know, you tell them to do it and they do it. They’re just waiting to be told what to do. And that makes it easy. And it’s very self affirming, I guess, you know, to realize you have that kind of power.

Mary Wesley: Well, Phil, thank you so much, it’s been wonderful to talk with you,

Phil Jamison: Likewise, and I appreciate your, you know that you’re working on this and I appreciate you reaching out to me about it.

Mary Wesley: There’s so much more to say about Phil. We talked for three hours over the course of two interviews! So you’ve just heard a portion of our conversation. We also talked about the incredible Dare To Be Square events, which he pioneered, the connection between contra dancing and modern western square dancing, stories about his most memorable gigs…for example – he was the official square dance caller of the 1980 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid! To hear more from our conversation and to check out a whole host of great links, photos, and recordings please visit podcasts.cdss.org.

The track you’re hearing is titled “In That Faraway Place.” Phil’s playing with some of his students from Warren Wilson College and a collaborating group of Chinese musicians while on a cultural exchange trip to Shanghai in 2017.

Thanks for listening to From the Mic. This project is supported by CDSS, The Country Dance and Song Society and is produced by Ben Williams and me, Mary Welsey.

Thanks to Great Meadow Music for the use of tunes from the album Old New England by Bob McQuillen, Jane Orzechowski & Deanna Stiles.

Visit podcasts.cdss.org for more info.

Happy dancing!

I want to give special thanks to a few people who have helped From the Mic come into being: Will Mentor, Adina Gordon, Max Newman, Lisa Greenleaf, Julie Vallimont, Ben Williams, David Millstone, Phil Jamison, and Jeremy Carter-Gordon, I can’t thank you enough!

Ben Williams: The views expressed in this podcast are of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect those of CDSS.