Dancing is magical. And if you’re willing to dance with someone you don’t know, then good things can happen I think. And you put it in the context that you’re dancing not just with a partner, but you’re dancing with a whole community of people who are very supportive and joyous and having fun, that allows us to be optimistic.

~ Penn Fix

Show Notes

Meet Penn!

Meet Penn!

“From the very start of my career as a caller and dance organizer I was concerned about creating a welcoming environment in order to encourage newcomers and in particular the next generation of participants. After retiring in 2019 from my family business, I have refocused on this concern. Our community has worked hard to address issues around inclusion and safety. But have callers expressed concern about the dance compositions themselves. Are they accessible to newcomers? As a dance composer I have witnessed and contributed to the ever-increasing complexity of contra dances over the years. Today, I am concerned that these dances serve as a barrier to new dancers. Yes, some newcomers appear to get through them but at the end of the evening are the dances fun enough for them to return to dance again? The age-old question whether we should gear our evening to the experienced dancers or the newcomers is more relevant than ever today especially in light of our aging community.

I learned to dance in the Boston area and grew to love it in the Monadnock Valley of New Hampshire. For three years beginning in 1977, I danced five nights a week before moving back to my home in Spokane, WA. There I had no choice but become a caller; I learned in a vacuum in which I leaned heavily on my love of dance and skills as a teacher and coach. In the spring of 1980, I organized the first contra dance series and began calling that August. That series continues today along with a Wednesday contra dance series I began in 1988. My first contra composition was in 1981 culminating in a 1991 published book called Contradancing in the Northwest. Since then, I have 30 years- of unpublished compositions. I co-founded the Lady of the Lake Music and Dance camps with my wife Debra Schultz – Fall Weekend (1981), June Week (1986), and Family Week (1992). I also served on the boards of the Washington State Folklife Council and the American Folklife Center (Washington, DC). After serving on the board of Spokane Folklore Society forty years ago, I have returned to the board where I am currently Secretary.”

Sound bites featured in this episode (in order of appearance):

- Penn calling the dance Hillsboro Jig by Bill Thomas to the music of Applejack on May 3, 2014, in Peterborough, NH, at the “Kwackfest” dance to celebrate the life of Bob McQuillen.

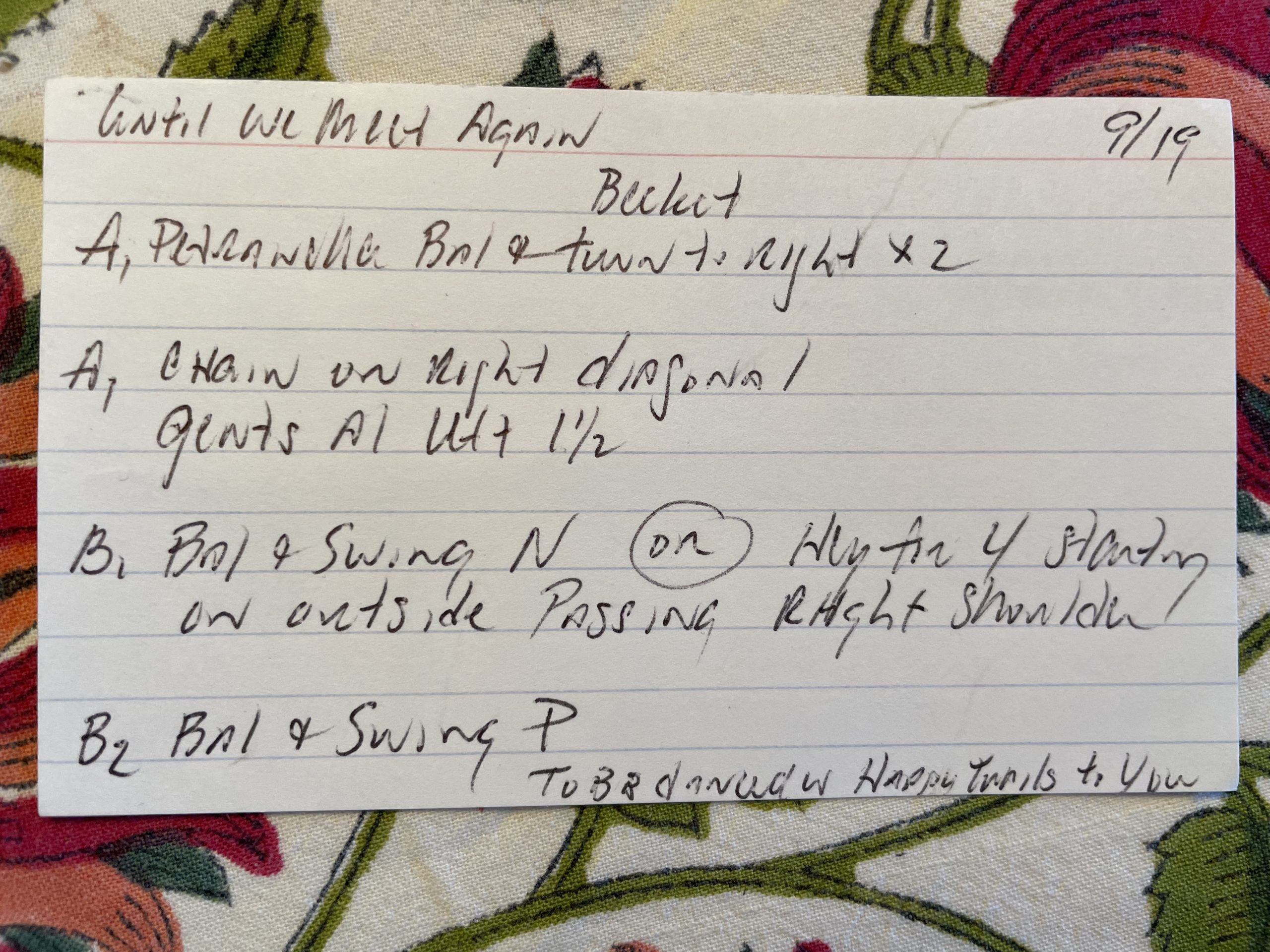

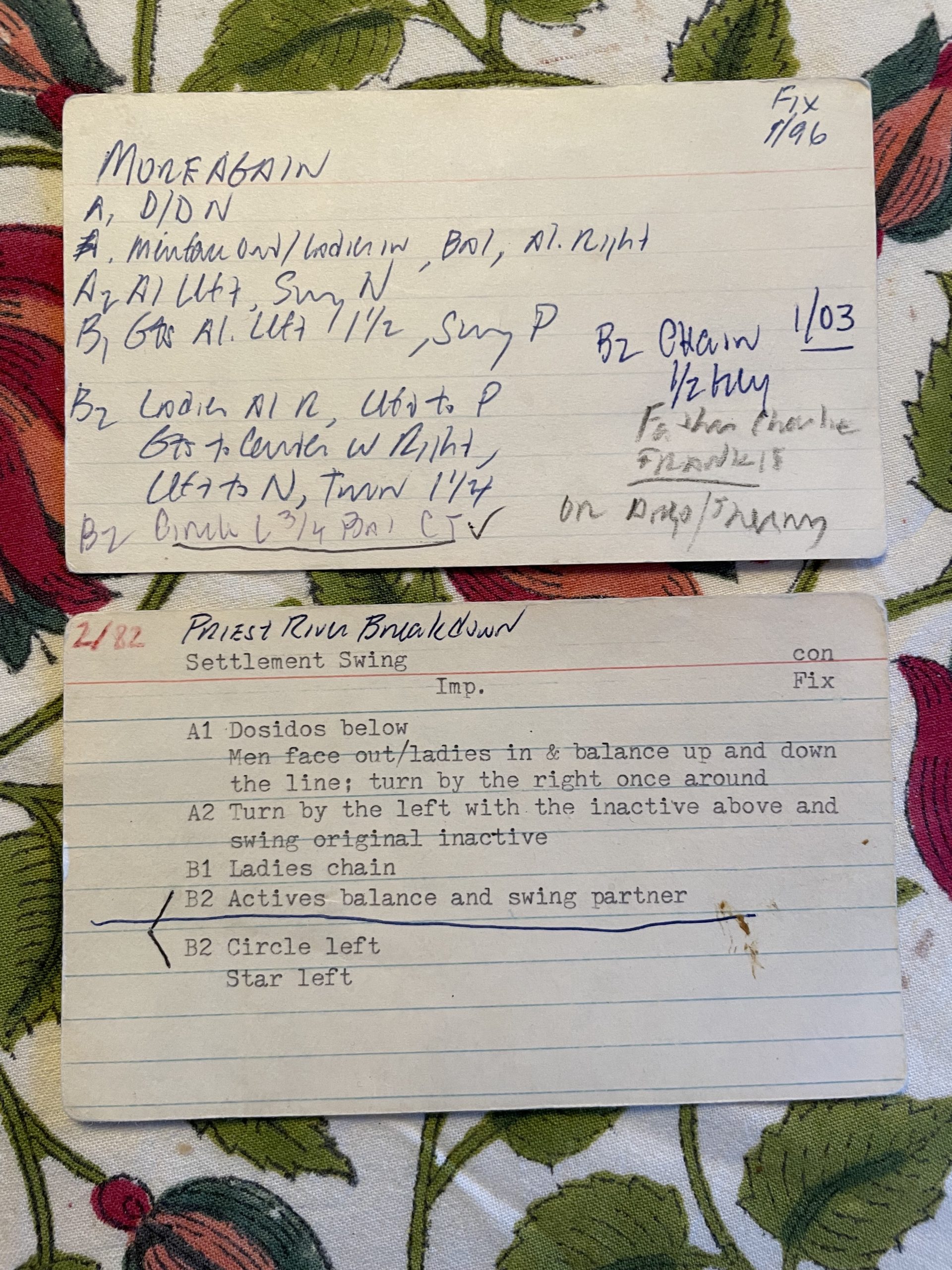

Dance Notation

From Penn: “Back when I started collecting dances, there were very few ready sources of dances. Subsequently, I carried a small notebook in which I literally wrote down dances as I danced them. For the first couple of years, I transferred these dances via typewriter to 3 x 5 cards. Once I started composing dances, I started handwriting them onto the cards. I continue this practice to this day.

I selected three cards [see below]. Settlement Swing written in 1982 was initially named Priest River Breakdown but quickly changed to Settlement Swing in honor of the old school house we danced monthly in the small community of Priest River, ID. Years later in 1996 I rewrote the dance to include a universal partner swing with various alternatives and called it More Again after a phrase my daughter used to say.

I continue to compose dances. One of the more recent ones, Until We Meet Again, is a companion to Dean Snipes’ Happy Trails to You.

In preparation for a dance in the Inland Northwest I choose one or two dances that I really want to call and then pull out a bunch of dances that either build up to those two or are there in case a lot of newcomers show up halfway through the dance. I will stack cards in various piles and spread out in front of me. I usually start with the same two dances – a circle dance (Cabot School) in which I can be on the floor teaching the swing and then a contra. From there I start pulling from my piles of cards. It can certainly be organic.”

[ Click on image to enlarge ]

Episode Transcript

Click here to download a transcript.

Ben Williams This podcast is produced by CDSS, the Country Dance and Song Society. CDSS provides programs and resources, like this podcast, that support people in building and sustaining vibrant communities through participatory dance, music, and song. Want to support this podcast and our other work? Visit cdss.org to donate or become a member today.

Mary Wesley Hey there – I’m Mary Wesley and this is From the Mic – a podcast about North American social dance calling.

Hello friends, welcome back to From the Mic. Today we’re traveling to the Inland Northwest for a chat with dance caller, composer, organizer, and devotee, Penn Fix. Penn learned to dance in the Boston area and grew to love it in the Monadnock Valley of New Hampshire. After three years of dancing five nights a week he moved back to his native home in Spokane, WA. There, he says, he had no choice but become a caller and help build the dance community he wanted to be part of.

In the spring of 1980, he organized the first contra dance series in the area and began calling that August. That series continues today along with a Wednesday contra dance series he began in 1988. With his wife, Debra Schultz, Penn co-founded the Lady of the Lake Music and Dance camps on Coeur d’Alene lake in Idaho. He has served on the boards of the Washington State Folklife Council and the American Folklife Center. After serving on the board of Spokane Folklore Society 40 years ago, he has returned to the board where I am currently Secretary. Penn is also a dance composer and historian. In 1991 he published book called Contradancing in the Northwest and also has 30-plus years of unpublished compositions.

We cover so much in our interview! Here’s Penn.

Penn Intro

Mary Penn Fix, welcome to From the Mic!

Penn Well, thank you very much. I’m really looking forward to visiting with you.

Mary I am too. We were talking earlier that we’ve had a few missed connections. We’ve been in roughly the same place a few times, but didn’t really get to hang out or have a chat. So it’s nice that we’re sitting down to do that now. And where are you speaking to us from today?

Penn I’ve been living in Spokane since 1980. I was born and raised in Spokane, and then I went off to college and then found myself teaching in a public alternative high school in Newton, Massachusetts, in 1974. It was called Murray Road School, and it was an annex of Newton North High School. So I was there for five years and then moved back to Spokane late Fall of 1979 and have been here ever since.

Mary Wonderful. And when and how did you start dancing?

Penn Well, that’s a great question because I feel pretty strongly and I think I will reference things from what callers have said and part of it is just my story. But I think Ralph Page once said that in order for you to become a caller, you should dance, maybe five years or something like that. But I truly feel that my dancing experience has really influenced how I call and what I call. I had never, ever really danced before in my life until I fell into contra dancing and it wasn’t unlike anybody else’s story, and that’s the joy of this, this whole trip. But when I was teaching at Murray Road one of the things we did was we played around with units of time, and so we would study one thing for a week. So I took a bunch of students out to Sturbridge Village for a week, and we spent the whole time there. They had a dormitory that we could stay at and part of the day the students were in the archives and part of the time they were dressed in costume, working in the living history museum farm. And then in the evening the staff would take us through certain things. They had a big new education department building and we did dancing. And it was dancing from, you know, 1790s to 1820. And the person that lead it was the person in charge of dancing, her name was Lila Farrar, and her sister Edith is a good friend of ours and she lives here in the west and sort of followed a bunch of people out here and she’s a musician as well. So I danced there in June, just one dance and then about two months later, I was in the White Mountains and some friends and I ran into each other and they took me to a dance in Tamworth, New Hampshire. I’ve been told that it was probably a Dudley Laufman dance. I don’t remember, the only thing I remember is everyone was moving around so fast and I just was totally lost, I remember people dancing without shoes. I remember I was kind of the last person to leave having just this great time.

And then my next memory is that, and I probably got it through Lila though I could be wrong. I decided the way to really learn how to dance was to go to a weekend. So CDS Boston center was sponsoring a weekend in the White Mountains in Cardigan Lodge. It was September 1977 and the instructors were George Fogg and Vivian Winston. And so my first real experience with contra dancing was actually with English country dancing. It was basically an English country dance weekend, and I’m forever grateful for that. Rather than…most people just get thrown right into a contra dance. But I learned some really basic important things that I probably wouldn’t have if I had gone straight into contra dancing and that was the element of giving weight. Most of us, when we think of that we teach it in the context of a swing. But in English country dancing, at least the way I was taught, there are other moves that have opportunities of giving weight. And when you do that, it really smooths out everything. So, for example, when I call a dance, oftentimes I will teach people how to circle because more often than not, they don’t circle in a way that allows them to move smoothly and also move around in time. And if you give weight in a circle, it actually allows you to do that. The other two things were the idea of dancing as a group and dancing with people rather than just your partner. Obviously the forward and back is the most obvious thing in contra dancing, but there are a whole bunch of other kind of moves that, at least at the time George Fogg was teaching, that you look and be aware of the people around you and you move together. There was a real power in that and a real fun nature to doing that.

Then the final thing obviously, was the connection with moving and music. And of course, the music in English country is so melodic and so obvious. It was much easier to follow the moves and understand how the moves related to the music. But as importantly with English country, you never want to be caught standing still and so you learn to use the music and move your feet. So like in a hey or something you didn’t dance to a spot. You finally arrived at that spot, but you had this time and what did you do to move to the music? So you slowed down and stuff. So those are the takeaways I learned from dancing English Country and I’m forever grateful that that’s what I did. Then of course, there probably were posters and stuff at that weekend, and so I fell into contra dancing and like everybody else, it was just crazy. It was a crazy time—I danced five nights a week. I danced on Monday at Concord with Yankee Ingenuity and Tony Parkes, and then Tuesday was Brimmer and May with Ted Sannella and Tony Saletan and then Thursday was Tod Whittemore in Cambridge, usually with Rodney and Randy Miller, and then there was always something going on in the Scout House.

Subsequently I got to dance with all the people—all the major callers from that time period. But the thing that I really loved was I fell into dancing in New Hampshire in the Monadnock Valley. Taking the highway 3 to 101 and then going to small communities. My favorite was Francestown, which is this lovely, lovely town hall with windows on both sides and a big stove going. And you park your car and the doors are open and the light’s coming out and the music’s coming out, it’s just that classic thing. Alan Block lived in Francestown so a lot of times he was playing and of course Jack Perron was calling. So I loved dancing there and I loved the sense of community and was such a contrast to the urban dances at Scout House and Brimmer and May where you would have hundreds of people dancing and these smaller dances had 20 or 30. Dublin was another great place to dance too. So that’s how I learned to dance and just totally fell head over heels with it.

Formative dance experiences

Mary Amazing. You’re just describing a whole landscape, you know, physical and also experiential. I don’t know if you want to share any more about some of those dance leaders, callers or musicians or people who stood out to you. I mean, part of this podcast is sort of taking a snapshot of dance calling now. But it’s also hearing the living memory of our history and our dance community. And you got to be active and time it at the right time in your life when you just had the time and the space and that sort of appetite to just eat all that up. So I just would love to stay in that realm a little bit more.

Penn Sure. It was a foundational moment for contra dancing. The late 1970s into the early 80s, you know, a lot of what we’re doing today was built on that foundation. There was a real transition going on during that time period. We can certainly talk about that and context of how people changed in terms of dancing, how composition changed, how the music changed, how things were being played. But unlike some people who sort of fell in to calling, I was very intentional because I knew I was returning to Spokane to help run our family business, which is, we’ve closed it now, but it was 132 years old. It was the oldest family owned jewelry store in the Northwest and was started by my great grandfather. So being a history teacher, you can understand that I shared the appreciation and sometimes the burden of that knowledge and saying, well, the teaching, the program that I worked at was closing and so it was a good time to try this. But having said that, I knew that going to Spokane, there would be absolutely no contra dancing. So I was very intentional in sort of thinking that I needed to learn how to call and I needed to organize dances if anything was going to happen.

And the difference today, I think today there’s a lot more opportunities to learn how to call from going to weekends and workshops and having mentors and lots of people that are willing to to help, which is really great. And CDSS has been great in that way and all the organizations associated with communities have done that too. But there really was a vacuum and so what I did was I taped everything for about two years before I left. And then I listened to tapes. The one book that I found, because, again, there wasn’t much there was Don Armstrong’s book on contras and how to do it. So, I started listening that way. And then the other thing is in terms of repertoire—today, of course, you can just go online and do anything, you can see YouTubes of stuff. But back then that was not the way. There were a few publications, but not very many that had dances and so subsequently I was always carrying a little notebook and writing frantically the dances down and that sort of thing.So I wasn’t taught directly, but I certainly paid attention to the callers. And so this circles back to your original question in that all these callers were just, very impactful for me, not only as a dancer, but as my future as a caller. Tony Parkes was one that really stood out.

Tony is a real technician. Tony always gave you a good dance. It was never a great dance but it was always a good dance because he was so intent on first, the ability to teach but also in terms of how to call. And so I listened to him on my tapes and it became very apparent what he would do is that he would say, you know (in this case, I apologize for doing Ladies Chain,) but he might say, “all the ladies chain across,” and then two times after that he would just say, “ladies chain,” and then the next time he would say “chain.” And he would do that all the time. And so I really learned that mechanism of calling that what you want to do is use words, multiple words, but not continue to use those multiple words and know where to call and then he would drop out certain areas so he was great that way.

Duke Miller, I danced to and Duke was amazing. When I saw him, he could barely walk and he would sit in a chair and he was in Western Mass. He was a schoolteacher in New York and would come up in summer. He did this one weekly dance for 30 years and what I learned from him was that you could project enthusiasm for calling and for the dance without having to move around at all. You would think, God, this guy’s up there just, you know, and you look at him and he’s just sitting there. But he used his voice. He used to say—because he did lots of singing calls—he’d say, “Anybody can sing in B-flat.” So he was great and then, of course, Bob McQuillen always played with him and then occasionally he would rope Rodney Miller in playing too. The thing that you learned from Duke was that familiarity of dances were things that people wanted. So more often than not he had the same program every week. He might throw in one different dance or something like that. And for me as a caller, I realized, because I started a weekly dance in Spokane in 1988 and I was calling every week, 35 weeks in a row or something, that I didn’t have to have a new dance every week. I learned that people actually like certain dances and they look forward to it.

Another one, Ted Sanella, of course was great and his death really left a vacuum in the contra dance community that was never filled. Because you had Ralph Page and he was sort of the guy, and then when Ralph died then it was Ted. And then Ted died too damn early. There wasn’t enough time. And maybe the world changed enough for the next person to step in. But, Ted, I learned generosity, he was very generous. He wrote a lot of his own dances, but he didn’t necessarily only call his own dances. He called other people’s dances and certainly supported his community. Callers were always sending him dances to review and he would give feedback and that kind of thing. But he, too, had huge enthusiasm when he was calling. You knew he loved to dance and stuff.

Jack Perron was another one. Jack lives in New Hampshire and he was calling most of the dances in the Monadnock Valley. Jack was just, and still is a very singular person and fairly unenthusiastic but happy to call in a way. So I used to call him “Happy Jack.” He had a great repertoire, but he was so nonchalant. He had this big book and he would sit there right next to a speaker with his book and he’d flip through it, and at times he’d just say to people, “Here, pick out something and I’ll call it.” And then someone broke into his car and stole that book and he never called again.

Mary Oh my gosh!

Penn I know, it was such a loss, you know because I have great memories of Jack. And what I loved about those smaller dances was that you just had a piano player and a fiddler. Like Harvey Tolman, I can’t remember who he was playing with, but in Harrisville, which was the precursor to Nelson. You know it was just a lovely place to dance. And then Alan Block with a piano player or somebody it would be just great, too. Another person that I remember was my good friend Tod Whittemore, who was sort of the young person of the group. I think Jack was fairly young, too, but Tod was certainly the next generation, and he’s certainly embraced the tradition. He had grown up dancing with Duke Miller out in Western Mass and stuff. So by the time I got in contact with Tod he was calling a regular dance on Thursdays in Cambridge, often with Rodney and Randy. And that was sort of the highlight of my dancing in Boston always was just being able to dance with Tod. He was always coming up with new dances and that kind of thing. And when I started writing dances, I would send them to him and then he was the one that was responsible for, sort of making me become, as my wife called it, a very mini celebrity at the time.

There were other dances, too, like [the band] Roaring Jelly had a dance in Lincoln and so we would go out there and dance. And then I actually, in 2019 came back for various reasons to New England and actually got to dance to them, so that was fun. I think they were dancing in Lexington this last time in 2019.

Those are the kind of people that were out there calling. And like I said, it was a grand time to dance. I mean, five nights a week, what more can you ask for?

Dancing and the folk process

Mary Amazing. Yes. So what were some of the changes that you were kind of in the midst of or that maybe now you can look back on?

Penn Well, let’s see. Where do you start? They are all interrelated because they all occurred at the same time. I mean, if I had my life to live again, I probably would become a folklorist. I certainly was very proud of the fact and embraced the idea that contra dancing was part of the folk process. At the time, English country and I danced some English country just recently and realized, boy, this stuff has changed so much. But back then it was sort of, you know, the Playford stuff and that was it. and so it was presented in my mind as something that was stuck in a certain time and I always felt very proud of the fact that contra dancing sort of moved along. And certainly clearly, looking back now it was doing that, as I began to dance in 1977.

Mary Moved along in terms of kind of, shifting and changing?

Penn Yes, for example, let’s just start with dancing. The dancing moved from mostly, I would say at least half the dances in 1977 were basically quite a few were proper dances. Meaning you were not crossed over, almost all the dances were asymmetrical, whereas even if you were crossed over, the active couple was the one doing something. So I remember one dance, I was listening to it just a while ago on my tape: Tony Parkes called this the final dance of the evening, and it was a proper dance in which no one swang, and that was the final dance evening and the crowd went crazy. Yeah, it was just like, whoa. But what changed was that drive as more and more people wanted to dance they had less and less patience for standing and waiting until they got to the top of the line to do that. Callers used to be, we were told, well, because of situations like that, you really should call all the way up and half way down the line. And unfortunately, I told that to too many people here and in some places they continued to do that, even though dances are very symmetrical and it’s not necessary.

But that was the big change, was that dances became more symmetrical and there were two things that did it: the circle left three-quarters and the Becket formations. And those occurred pretty much…the circle left three quarters obviously was a little earlier, starting to happen in the late 70s and definitely into the early 80s. But the Becket formation, Jack Perron used to call the Becket Reel all the time and it never caught on in terms of…it was always sort of a weird dance. But the formation itself basically allowed everyone to swing their partner at the same time and that’s what drove the changing of the dances. And at the same time, callers started to write their own dances and that was relatively new. I mean, it was happening, but today it’s all the time. But back then, we did a lot of traditional dances, not only chestnuts, but a bunch of others that in Ricky Holden’s book written in the 1950s there’s a bunch of dances there that were used and that kind of thing. So the dance scene really started to change so that you ended up dancing with your partner, everybody did, that was a major thing and that continues to today. So a move like, “active couple down the center, with your partner, turn around, come back and cast off,” no one knows how to do that. If you want to do a hard dance, that’s what you do. [laughter]

So what happened then, too, was the other thing then evolved, and I’m speaking not only as a caller, but as a composer, because as you know, I started writing dances, my first dance was in 1981. But the other thing, it changed, besides everyone being able to swing their partner at the same time was what they call “flow.” And there is one major thing as me as a composer I thought of as a dance that Ted Sanella wrote in 1979 called “Scout House Reel.” It basically had a ladies, excuse me for using ladies as opposed to robin, but a chain into the Robins doing then a do si do once and a half. That was revolutionary. It doesn’t sound like it anymore—and then you would swing your neighbor or something, as I remember or partner. But that idea of flow—and then the other one came from the square dance world. There was a guy named Lonnie McQuade out of Chicago and in 1980 he wrote a dance called “Joy.” And Joy has a right hand star, which is the right hands physically, into a chain, into a hey. And so that whole thing was revolutionary, that chain Into a hey, and all of a sudden people started wanting to do that kind of flow on that.

And then the other thing that started to happen too, and this is all happening slowly during the 80s for sure. But by the early ’90s it had really occurred, was that composers then started wanting to help people move from one move to the other. Reflecting back on my English country days, but particularly the early contra dances we did, they were very structured. And if you wanted to connect them, you physically had to be aware that, you know, this is a chain and then we’re doing a right and left through and then we’re doing a star. There were little things that you were taught because some of these moves actually moved you faster across a set than you wanted to. And again, there’s little things I used to teach, like a little backup step to wait for the music as opposed to going in to—like in Lady Walpole’s Reel, there’s a thing where you do a chain and then go into a right and left through, and then you have to back step a little bit and then go into the going back across the set.

So composers started wanting to connect everything so that people didn’t have to think about that. Meaning you would move into the chain, into the hey, into this, into that. And then even today, it’s getting to the point where they’re taking moves that are four count moves, two count moves, all this to fill that space of time. As a result people dance differently than they did back then. So what I’m talking about is the dances changed, but then the dancers changed too in how they danced as well. So the dancers move differently. At their worst, sometimes I’ll complain to people—and I can get away with this because I’ve been calling for 40 years—but I’ll say to people, “You know, you’re just not really dancing to the music. You’re just sort of moving through everything.” And I say, “But it’s not your fault, it’s my fault and other composers for writing these dances the way they are.” They just flow so nicely that you sort of get lost. You forget where you are in terms of the music. The better dancers know when to stop, but a lot of people don’t know when to stop the swing and then move into something else.

Back in 1990 [correct date is 1981] I started Lady of the Lake, in part because of my experience with Cardigan Lodge and thinking this is the way our community will really learn how to dance is if we go out on Coeur d’Alene Lake and spend the weekend dancing, that was in 1981. So what happened is in 1990 I was at Lady of the Lake and I usually didn’t program myself to be a caller, but I did because it was our 10th anniversary. And so I started making points about how this has changed. And I basically got a little carried away and claimed that this lacked the structural integrity, these dances anymore. And so people started wearing buttons that said “Integrity” on them. And I’m not here to claim that we need to return to this, it’s just an observation that this is how it’s changed, and music has changed along with it.

So the way the music is played, and I have been thinking a lot about Bob McQuillen because Lady of the Lake was a really integral part of his life. He came to our camps probably 15, 20 times in his lifetime and really appreciate what he did for our community, meaning not Lady of the Lake but our entire community. He certainly was an example of someone who wrote his own material, his own dance tunes and that serves as an example for others to do that. And today, I bet most people are playing tunes that were written in the last 50 years. Whereas when I first started to dance there were very few dance tunes that were new and being written and so they were relying on Irish tunes and some of the other stuff and traditional New England chestnuts. So these people started to write tunes, but then they started to write tunes in relationship to how people were dancing and playing them. So that there was no necessarily phrasing. There used to be one way you could really distinguish like an old time band versus a New England band was that the New England band really emphasized the phrasing so that dancers would know, okay, part B is starting or, you know, whatever and the tunes were very melodic and there was a difference between an A part and a B part.

And all that changed in a sense, and it reflected sort of what was going on on the floor too. So you have all this flowy stuff going on and you have the musicians playing differently too. You know, more emphasis on rhythm and more emphasis on really pushing through and on and on and on. So going back to what I originally said is that the dancers changed the way they danced, the dances changed, and the music then changed as well, and it still is evolving. I just played with this great band called Countercurrent who are two young people, and they really have, in my feeling, have embraced some of the traditional stuff in a way that they interpret it contemporarily but it feels, you know, like it has real connections with the past, too. So I’m very excited about that. So I’ve talked a lot, I’m sorry.

Mary No, it’s great. It’s super interesting just to hear about that butterfly effect just going around and everybody influencing everybody else in different ways.

[ Penn calling the dance Hillsboro Jig by Bill Thomas to the music of Applejack on May 3, 2014, in Peterborough, NH, at the Kwackfest dance to celebrate the life of Bob McQuillen. ]

Leaving New England

Mary I wonder from your first person perspective, as what I’m hearing is you were among the young people who were kind of getting excited and pushing forward some of those changes, seeing, “Oh, it’s actually great to be able to be active all the way through a dance.” What did you witness as that change was gaining momentum and you were seeing some older people who had a longer view and this felt new and disorienting. What were some of the reactions that you witnessed and what was your kind of position on it all?

Penn That’s a great question. I don’t think I realized it. I mean, it was such a momentous sort of thing. We were so caught up into it that we just were doing it. And the older people chose to participate and they just were right there. I don’t know if he’s a great example or not, but a good friend was Ernie Spence. And Ernie was this gentlemanly dancer who probably wasn’t as old as we thought he was but we were the generation not to trust anybody over the age of 40. So anybody older than that, we’re like, “he must be really old.” But he danced his whole life in that context of all the young people and stuff and whatever was going on. I have a very distinct memory and it has always haunted me in a way, was that Tod took me to a Ralph Page dance and it was on a second floor somewhere and we went in and it just felt like a dark room. It was during the day, the light was coming through the windows and Ralph was there with a phonograph album record player and there were about eight couples and they were all my age now [laughter] and they were dancing and they were doing all Ralph’s dances and stuff. And so I always thought, I don’t want to do that. I don’t want to be ever in that position. So I don’t know if I can really answer your question. Obviously, I think it’s easier to talk about it now in the context of me being an old person in that, as opposed to being a young person and aware of that.

Part of the issue, too, is that I left New England October 1979 and while I came back every year for the next five years and danced and called and did all kinds of stuff, I really left that whole thing. And going to Spokane was such a different experience because no one had ever danced contras. The difference between the Northwest and New England was, however, that there were organizations that arose, they called them Folklore Societies, that sponsored primarily concerts. And this was in the heyday of the back to the land movement and the roots and stuff. So young people were really interested in both old time music and Irish music in the Northwest. And so there were folklore societies, Spokane Folklore Society was established in 1977. There was a Corvallis one, Portland, Seattle, all over the place. And they sponsored concerts and they had newsletters and they had this infrastructure.

And Sandy Bradley then started calling dances in 1974-75 so then she was calling mostly square dances. But as contras started to filter in, she started adding some contras to her repertoire as well. But she came to Spokane about five times between 1977 and 1980. So when I went to Spokane there was the Spokane Folklore Society, they had a newsletter. I decided I was going to find a dance hall and start calling contra dances, knowing at least that there was some help there, that I didn’t have to do all the work. And I went to a concert that, oh, I’ve forgotten his name now, was there and he was also a caller. So he had a square dance and a concert at the same time and I met Bob Childs there. Bob Childs was in Spokane because—it was a fairly unique thing—there was in the community college a string repair instrument program, a two year program taught by a guy named Anton Smith. Anton learned to make violins in Europe and so he really wanted to have that kind of a gig going on rather than just helping people repair violins and stuff. But Bob came to learn how to make violins with him. He was there for a full year and then Anton decided he didn’t want to keep doing that so he moved to Oregon and Bob followed him.

I met Bob Childs in November or December of 1979. And he was a caller and a fiddler and so I immediately grabbed on to him thinking, thank God I don’t have to call. We started dances, a regular dance series in January. We did a second Saturday contra dance and then a fourth Saturday Square dance, and that was headed up by a guy named Wild Bill Reagan who called and then the fiddler there was Geoff Seitz so we had a string band. Jeff went on to win Galax and do all kinds of stuff. He lives in Missouri now where he was born. The house band for the contra dancing was an Irish band called Irish Jubilee. So Bob really helped them learn kind of how to play contra dance music because usually in the Northwest you either had an old time band or else you had an Irish band. There was never a piano player at all. So you had to learn to live with that, but at least with the Irish stuff, you usually didn’t have a hammered dulcimer, which drove me crazy. Because you really couldn’t hear any phrasing with a hammered dulcimer. Bob left after about six months and then I had to call. But where I’m going with this is nobody had ever danced contras before. Nobody. If you said “chain,” everyone would look at you like, “what the heck is that?”

So I learned how to teach dances, really had to learn. Whereas the hard thing for callers today, I think for most of them, is that they never really have the opportunity to really teach, because most of the people know how to dance. And even when you try to break it down and say, “Well, let me teach this,” half the people are doing it anyhow, so it’s really hard to learn. So I was really grateful that my experience coming to Spokane was, and I was a teacher and I was a basketball coach, so I knew how to break things down. So all that played into it, but I really learned how to teach moves. One of my teaching things, too, was that you had to learn how to teach it in different ways because not everyone learns the same way. So that was it.

And then Bob Childs, as I mentioned, was amazing because of the repertoire he had. While he was not born and raised in Maine, he lived in Maine long enough and really got caught up into that whole community world of dance and music there and ended up having great friends, Smokey Mckeen and some others. He had this really simple repertoire because if you remember I was collecting all these dances, but there were dances that were being danced by contra dancers and most of them were not appropriate for the people here in Spokane at the time. So Bob had these community kind of—dances I use today when I go into one night stands and family dances and that kind of thing. They’re mostly reels, more often than not he wouldn’t even teach a contra dance in an evening. He would use reels and squares and circles and stuff. So I was really grateful for him to be there, because I didn’t have to jump in and start learning but then when I did, I had the correct repertoire to do it.

Building a dance community in Washington state

Mary So you’ve really had quite a significant hand in shaping the dance community that you wanted to see and wanted to be a part of. So…

Penn Absolutely.

Mary Yeah, so do you want to fill that out a little bit more, so after those early days of starting from scratch?

Penn The amazing thing I did this, and it’s so funny, I was like, “How did I do all this stuff?” Because I was working full time in our family business at the same time and I didn’t meet my wife until 1985. So from 1980 to 1984, I was just mostly dedicated to doing stuff and so Spokane is a real hub of the inland Northwest and so we drew, when we started doing our dances, started drawing from people from outside the area. And they would talk to me and say, “Hey, we’d like to do dancing in our community.” So I started the dances in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, which is about 30 miles away. Then I started a dance in Sandpoint, which is about a two hour drive northeast of Spokane and I did one in Priest River, which is directly north, about the same distance, and then Colville the same way. I have recently written articles about all of them because most of them were filled with back-to-the-landers kind of people. Colville was mostly commune folks and Priest River were people living literally in the woods and stuff.

I also helped, though I didn’t start it, a dance in Moscow, Idaho, actually Pullman. It came out of some international folk dance people who were doing stuff there. And then I would go on a regular basis to Seattle probably about every 4 to 6 weeks to call it a place called the G Note Tavern. They had dances every Thursday there. When I first started, people would come up and say, “You know, this is okay, but when are you going to call a square dance?” So it was still very oriented towards squares and I was kind of one of the few full time contra dancers, or perceived that way. In those first four years, I did about 60 dances a year and I put about 10,000 miles on my car each year. And of course five and ten dollars and that kind of thing, but I always was able to write it off because I had another job. So I just kept track of all my mileage and everything and that kind of thing. I also had the opportunity to go back east and call stuff like that, too.

Why be a caller?

Mary Why was it important to you to do this?

Penn You know, that’s so amazing and I look at it, too, because, like I got frustrated. You know, one of the things I realized is that I was a dancer who called, until I became a caller who danced. And so I was still in that realm of a dancer who calls and was frustrated that people weren’t learning fast enough for me so I could call these great dances that I learned from back East. One of the reasons for Lady of the Lake came out of that sort of motivation that I had. I mentioned Geoff Seitz and his string band. He had woman named Marsha who was a banjo player—and incidentally all the string bands had women banjo players, I don’t know why back then. But she lived in a little town called Harrison on the east side of Coeur D’alene Lake and there was a camp that she recommended, which we’ve been using ever since, called N-Sid-Sen. I just thought of my experience at Cardigan Lodge and thought, “this is the way we do it, is we get our community out to the lake and we’ll be there for a weekend and by the end we’ll all be dancing better.” And so that was sort of my push. And then in 1988, probably for the same reason, I started a weekly dance in Spokane, which is on Wednesdays, which continues to this day, as does our weekend dance. And that was to the same reason, was that here’s an opportunity for people to really learn how to dance because they have more than once a month to do it. Because oftentimes they might miss a month so then all of a sudden it’s two months. I guess it got through that that’s what motivated me was that I wanted our community to dance, and I love dancing. For me, I never quit—especially during that time period—recording myself and the dances I went to, because I loved the music. I absolutely loved the music and I still love music. So for me that was the other part of it, was I really began to embrace the whole music scene and loved the playing of the music, too.

Mary Do you play as well?

Penn No, I don’t. I bought a bow once.

Mary It’s a start. Hey!

Penn I bought a concertina once. I have great respect for musicians on that. I remember, too, that there was a fellow named Roger Muat who was a classically trained fiddler, and so he used to play some of our dances here in Spokane. I just was always amazed at these fiddlers who could remember all these tunes. Roger was classically trained, so I had to feed him music all the time and then he would start playing a tune and all of a sudden the second part became really familiar and I looked at him and said “Universal B part, right?” Because he’d forget the second part. It just made me feel like, yeah, these musicians are amazing that remember all this stuff.

Mary Is calling kind of your way to be on the inside?

Penn I do and I alway ask permission and apologize profusely. I do play the spoons on occasion.

Mary Nice.

Penn Some bands put up with it. I know I played with Jack and Arvid, Jack Lindberg and Arvid Lundin for years. They were sort of the house band for the weekly dances and Jack once gave me a present of two spoons that had pads on them so you couldn’t hear anything when you tried to play on some. It’s a subtle thing, I said, “Okay, I get it.”

Mary But does that just come from a desire to participate in that way? Participate musically?

Penn Exactly. And I’ve had some very high kind of moments playing the spoons with bands that really like it and stuff and feel like I connect with that. The other way that dances have changed too is that dances have become more intricate. So callers oftentimes have to call more all the time. And so then the dancers never understand that maybe their responsibility is to learn the dance and in part, some of them are so complicated you can’t remember anyhow. So I’m one that wants to get out of the way of the music pretty quickly and so people sometimes get upset when I quit calling. But I also feel like I don’t usually call very complicated dances, and if I do, then I’ll continue to call. But I sort of feel like it’s the dancers responsibility to learn the dance. And if you do that then you have the joy as I do of dancing to the music rather than to the caller. So that is another great joy is just to be dancing and being carried by this wonderful music.

Mary Absolutely. What are some of your other goals as a caller? You’re talking about trying to get out of the way of the music, what else feels important to you to try to convey?

Penn Well, I like to convey the history of it. So my wife and daughter in particular, my son, not so much, but they claim I talk too much [laughter], between dances, and as I talk about a dance. I remember one person I heard you talking to who said she struggled with finding stories. I am full of stories, to the point where I’m probably a distraction. But I like people to know the context of the dance. And you know, I always start an evening with a circle dance which at certain times drives people crazy, called Cabot School, which was written by Ted Sanella in Cabot Schools in Newton, Massachusetts, and so I’ll talk a little bit about that. I might talk about Nelson and how the floor used to move a certain way, and also this is Bob McQuillen and we’re doing a tune of his. Or this is, whatever. So I bring in the stories, so I guess I try to have that perspective. If I can get away with it, occasionally I’ll teach something, and I’ll teach something like giving weight and not in terms of swinging, but in other moves and stuff. So I guess I do have some motivation in terms of a goal or something. But when I write dances, you know, some composers have goals about that, I really don’t. I just see a move that I think is interesting and I think, oh, well, I can play around with that and maybe come up with some other dance or something. But I’m not trying to do a dance that feels this way or that way. It’s usually not the case.

Composing dances

Mary Are you still composing dances?

Penn Yes, I am. I don’t necessarily have anyone to try them on, but occasionally I will send them off to people. The last person was very generous in that she hasn’t really given me feedback, was Lindsay Dono and she was using, what is it called, a poussette. She likes to use poussettes. And so I had just written some dances with poussettes in them, because I like it too and so I gave those to her. They were named Francestown and Harrisville.

Mary Nice.

Penn So everything, all the dances that I write, I title after things and places and people that are important to me. I guess I learned that from Bob McQuillen. When I was a kid Gene Hubert was…I only met him once but he certainly influenced me in terms of repertoire. An early composer of dances and publishing dances, which was very useful. Gene could never make a decent title if it killed him. And so I always wanted to say, “Gene, let me make the titles for you. You write the dances and I’ll do the titles.”

Mary Love it.

Penn You know “Gang of Four” or “Rotary Circulator.” Oh, my God. [Laughter] Things like that. And then the other composer that I always admired was Dan Pearl. And for Dan, for most composers, we all write lots of dances and maybe 1 or 2 stick. And Dan has written so many ones that really stick and I always thought that he probably had a board of people that would review all his dances and say, “Nope, Dan, you can’t release this one, that’s a bad one, don’t release that.”

Mary Heavily screened.

Penn I’m sort of moving around our discussion, anyway.

Looking to the future

Mary Oh, it’s okay. What has calling been like recently? I mean, and recent can be, you know, a broad term. We’re obviously still coming out of a major interruption to all dancing, the pandemic. So I’m curious kind of leading up to that and up to the present what are you noticing and what’s keeping it fresh for you?

Penn Well the interesting thing is that my wife, Debra Schultz and I got together in 1985. We met at a dance and she asked me to waltz. Isn’t that great? Best day of my life. And together we started doing June camp in 1986.

Mary Where is June camp? Remind me?

Penn Well, Lady of the Lake is on Coeur D’alene Lake, it’s on the east side and we have run three camps, which, I started the first one, the fall camp. But then Debra and I with a committee of people started the June camp in 1986. And then when we had our first child, Louise, we started a family camp in 1992. When we had the family and then Debra started helping with the business too, we were just too busy to do a whole lot of stuff. So I did the weekly dance from 1988 to 1991, when Louise was born, and then handed it off to Dave Smith and he did a smart thing, which was to offer a caller’s workshop, and a bunch of other people got into it and so we had a rotation.

So before Covid, the weekly dance was being supported by eight different callers and eight different bands. Right at the end I was starting to get back into the rotation, which meant that I would call maybe 3 or 4 times in a season from September through June and that’s about the only thing I was doing. And also, Deborah and I kind of retired from running Lady the Lake about 15 years ago. Before that, I called a little bit during that experience, but again, not doing a whole lot. We closed the business in 2019, right before Covid, so I started calling a little bit and I joined the Folklore Society and I was always on the board of Lady of the Lake and sort of helping in that way. So as a result I started getting back into it and being aware of some of the issues that are going on. The biggest one is the gender free issues and safety and consent and all that stuff. I’ve certainly been helped by my children, in particular Louise, who’s an exquisite dancer and plays violin as well and our son, to a lesser degree, is also a great dancer too.

So the most exciting thing for me is sort of having to reorient how I call in that context and how I think about it and sort of that process. In 2018 or 2019, the very first real contra dance, English Country Dance series was started in Portland the year before I did mine and so I would drive down to Portland and dance there. Craig Shinn and CHristy Keevil was there and some other people. So we had this reunion, I think 2018 or maybe 2019 and we were invited, I was invited to come to this dance and it was a very odd kind of situation, but we kind of called but then there was this younger caller who, before the dance started, really explained to everybody how you ask people to dance, how you do all this stuff. I remember Edith and I, and my wife sitting there going what the hell is this all about? And so it was just really for us, like, “What’s going on?” And then in the course of the last three years, it was sort of like, “Oh, I get what’s going on.” I get if we want young people to come into our communities, which has always been an issue for me, I want young people to come in, then the environment needs to be perceived as safe, and that’s a broad sort of definition of that.

Subsequently I initiated among our 8 or 9 callers the discussion about using gender free terminology. Fortunately, the Folklore Society has been pretty ahead of stuff, but still we’re in transition. I have been, starting in 2019, I started talking about, when I start my Cabot School Circle dance, I usually teach the swing. Now I’m saying to people, “This is the expectation of how you hold somebody.” So that it gives them a thing of, if someone isn’t holding you that way, you can tell them this is how you want to be held. So I started that discussion and then the callers, we talked and we all agreed about the issue of gender free. But nobody could agree on what they wanted to use so we’re still in that transition.

Because of Covid. I haven’t called much, but I finally called a dance this fall and I used larks and robins and it felt very natural, I was surprised. Actually. we had reconfigured our family camp into a camp that was more oriented towards young people and we were doing Larks and Robins and having lots of discussions. Lindsey Dono was there and Susan Michaels and other people. It was like, this is no big deal in my opinion. It was so easy to do. We do have a couple of callers trying to do positional calling, and that’s very, very difficult. I think it’s really challenging to the point where they went down to one community and I think turned off the community to the point where they decided they were only doing ladies and gents. But even the people who are doing ladies and gents are explaining the context of it, that it’s a marker as opposed to anything else, it’s not gender related per se. So I think that’s pretty exciting what’s going on there. It was in some ways a big deal but once I did, it wasn’t a big deal.

[ Penn calling the dance Hillsboro Jig by Bill Thomas to the music of Applejack on May 3, 2014, in Peterborough, NH, at the Kwackfest dance to celebrate the life of Bob McQuillen. ]

Mary What else excites you about the future? What’s on the horizon?

Penn Well, I don’t know if I’m going to answer your question but for me, contra dancing is a means to an end. For some people, it feels like contra dancing is the end. For them, they make a lot of decisions because it’s sort of the end thing. But for me, contra dancing has always been the means to the end, and the end is building community. Our Lady of the Lake is a brand that is so well recognized. People come to it and just say, “Everyone is so nice, everyone is so inclusive and everyone is this and that…” and that’s because we really laid the foundation, Debra and I, about community and programed in a certain way that did that. So I worry about community. I worry about dance in the context of community and we’re sort of at a situation, I don’t know if it’s still happening or not, where communities are big enough so that there’s a group of people dancing that are doing gender free and there’s a group that’s not doing gender free. And that ultimately, I mean, I guess if you pull it off, that’s fine, you’ve got your own kind of community. But it’s a different kind of community than in my mind. And so that is for me, the challenge is how you create an intergenerational community of dancers and Lady of the Lake is grappling with that right now.

We, in our June camp have a lot of older dancers that come and as they get older then they can’t come. And so if for no other reason we have to make adjustments to that and try to figure out how best to attract a younger audience. I’m not talking 20 to 30 year olds, I’m talking even 35 to 50 year olds. It’s hard, obviously, for people to get away for a whole week anymore and dance and some people don’t have the money and some people don’t have the time. So there’s a lot of things that we are working on. Family camp sort of fell apart right before Covid. We reimagined it with an intergenerational camp called Dance Some More and that went for two years and we made the decision to stop it this year. But we’re taking a lot of what we learned and trying to apply it to June camp as a way to continue it for a lot longer. So we’re very excited about that and that’s, I guess, where our focus is right now, my wife and I, is trying to figure out how that works and we have a really vibrant committee that’s working and we’re trying to attract younger people as well to help us with that and direction.

What really makes me believe it’s going to work is that we have a lot of young musicians and young callers coming up, and so usually their friends follow them, and so there are young people out there dancing as well. I just think this whole issue of what community is and how different groups interpret it is really critical and whether they’re willing to be open to working their community within the context of another community as well. That’s probably reflective of the whole world in many ways too.

Mary Yeah, I think about that a lot as our dance communities as kind of microcosms and can be really great spaces to work on some of those much bigger challenges of humanity.

Penn Yeah, it really is. It’s very challenging though but I think we have a chance. I think dancing is magical and if you’re willing to dance with someone you don’t know, then things can happen, good things can happen I think. And you put it within the context that you’re dancing not just with a partner, but you’re dancing with a whole community of people who are very supportive and joyous and having fun, that allows us to be optimistic.

Closing

Mary Yeah. Well, before I get to my three closing questions, I have to return and ask, do you still have all those recordings that you made, and it sounds like you continue to make, and are they archived?

Penn With any caller, I would recommend this, it wasn’t intentional, and I didn’t record myself because I wanted to hear myself. But once I started recording myself, especially early on, I was like, “I do not like the way I sound.” And again, thinking about Duke Miller and Ted Sannella in particular, I realize that you can control your voice and especially you can imagine in my situation where it wasn’t unusual for the whole contra line to just blow up, you know, to take the alarm and stress out of my voice was something I worked really hard at. So I would certainly recommend any caller that they record themselves just to say, oh, because you can really use your voice to help the dance along in a lot of different ways.

But the recordings, yes, the recordings that I did during New England, I sent to UNH, University in New Hampshire and they were very interested in that as well. And that included also, Frank Ferrell started the Centrum [Foundation] stuff going on in this includes the Fiddle tunes week. And then also for about ten years, there was a thing called The International Folk Dance Music Week, which was in August. What was brilliant about that was that he would bring in three different styles of dance, but also along with it, live music. So he would do contra dancing, he would do Balkan with Dick Crumb but with this great Balkan band, that was just wild. And then an Irish band or a Cape Breton group or something like that, you know, just fabulous stuff. But he brought Ralph Page up, and this was in 1980 along with Rodney and Randy. And then Tod came out and I set up a little tour ahead of time. And then the next year he hired Tod with Rodney, and Andy Davis came out to play instead of Randy. And then I think they came out even one more year. And then he brought up Foregone Conclusions after that.

But the result was, is that we just had this really great music and I recorded it all. So that went back UNH as well, a full week of that. And also McQuillen came out for 1985 for Fiddle Tunes, and Frank called me and said I’d like to have you call because they had a dance program and I’m bringing up Bob McQuillen. And I said, “Are you bringing out April Limber?” He said, “I can’t afford to.” I said, “You’ve got to have April out because there’s no point bringing Bob out because April knows all the tunes!” So I forgave my fee, I said, “Look, I’ll do it for free if you’ll bring April out.” So April came out. So I recorded all that stuff about Bob talking about how he wrote music and all kinds of stuff. So all that stuff went to UNH, it was really great. I was really thrilled that they were willing to take it.

Mary Oh I’d love to hear it.

Penn It’s just sitting here, so.

Mary Great. Well, my first question, which you’ve spoken to the larger theme of caller as historian, as archivist, as kind of keepers of a lot of aspects of dance history, culture, but in particular dance notation. Just by the nature of what we do, you have to have some system of recording and keeping your dance collection. I’m wondering what you do? Do you have cards? Have you moved to a database? What’s your notation system?

Penn Oh, I can’t do database. Oh, my God. I understand people doing that, but I just can’t do it. I can’t read a book on an iPad or whatever. I can’t do it, but I understand it. The way I call dance, at least when I used to do it a lot, I would have a bunch of cards that I always used and I would just spread it out in front of me. I would pick two dances I knew I was going to call and then I’d have all this stuff out here and it was just sort of an organic process that I would pick and choose dances based on what was going out on the floor and the music and that kind of thing. So I’ve always used cards and my cards, some of them are 40 years old and some are new because I’d just written new dances on that.

I was always, probably because I was a historian, I was really, really intent on making sure I got the name of the dance correctly and who wrote it. Early on, and callers don’t like to do this, but I would hire these great callers for Lady of the Lake and I would ask them if I could look at their calling box. So I would get dances that way. But also they’d look through mine and, and help me and say, oh, this is written by such and such. The person who never did that was so funny was, you just mentioned him and he had his own square dance hall and his singing squares and stuff.

Mary Oh, Ralph Sweet.

Penn Ralph Sweet. So we brought Ralph Sweet out and I was looking through his box, and there were a couple of dances that had these titles on them, so I said,

Ralph, this is my dance and this is called such and such.” So he laughed and said “Oh, yeah, I collect dances, but I never remember the names of them, so I just put names on them!” This is what I do. You know, it’s just like no, I want to make really sure that I have that correct, so yes. So that’s what I do, I still have my box. I have multiple boxes because I move things around and stuff, so that’s what I do.

Mary Nice. I also still really rely on being able to just physically spread my cards out and move them around. And yeah, I don’t think I’ll move away from…

Penn Many of the younger dancers like Lindsey, you know, has the thing, you know, it’s like, good for you.

Mary Yeah, it makes a lot of sense. I think I got halfway through trying to create some kind of digital backup of my cards. I mean, that story of Jack Parron’s binder is just a totally heartbreaking and terrifying thing.

Penn If we have a fireI got to make sure my calling box is gone with me.

Mary Yeah. So when you’re getting ready for a gig, do you have any pre gig rituals or things that you do to get ready? And anything that you do to kind of wind down afterwards?

Penn You know, to be honest with you, I do so little calling anymore, but I’m much more intent right now of really looking at my dances because I haven’t looked at them for a long time. And again, I go through the ritual of saying, okay, I’m going to do these two for sure. I’m going to start with these. And then because, especially in a community like Spokane, you can make the assumption that the level is 6 or 7 and then it’s really 2, or else a bunch of people come in and dropped it to 2. And so you’ve got to be ready to adjust pretty quickly. So I will have that in mind, I’ll have, okay, here’s my go to ones. Usually those are ones that are pretty simple, but they have an interesting move in them or something so that it’s just a little different so it doesn’t all feel the same. Sometimes I will have written a new dance and want to try it and so that is out there as well. But again, my role as caller versus dancer versus composer is that if people aren’t able to do it, then I’m not going to try to make it work, so that’s sort of the case. And then after a dance I’m usually pretty excited and my wife is still up and so we’ll talk about it. She’ll say, “How’d it go?” And that kind of thing.

Mary A debrief.

Penn A debrief, exactly.

Mary Nice. I don’t like to call it the postmortem. [laughter] And then my last curiosity that’s something I’ve been asking everyone in these interviews is if, you know, are you an introvert or an extrovert?

Penn Well, that’s a great question, because I have put myself in positions where I’m in the leadership of some form. I ran for president of my high school, I was dorm president in college and then I organized actually, folk concerts in college and then I became a teacher. And, you know really quickly, if you want to teach or not, when you stand in front of a bunch of people and do it. You might be surprised to know that at times.I felt like I was a fairly shy person but these sort of situations allowed me the confidence and sort of the protection, I guess to sound like I’m an extrovert. But I’m very comfortable talking to people. I was a retailer for 40 years so I learned how to talk to people and engage and that kind of thing. So I guess I am sort of…people would say I’m an extrovert, so at times I can be somewhat shy, but I also am able to step into the fray when called upon.

Mary Yeah, step into those different roles.

Penn Exactly.

Mary Nice. Well, Penn, it’s been so great getting to actually have a nice long chat. It’s wonderful to hear your memories and stories and hear about dancing in the Northwest. I hope that you continue to make your contributions and keep that community spirit alive out there. It sounds like there’s still a lot of great things going on, and I hope I make it out there sometime soon, too. I have called at Lady of the Lake one time. It was quite a while back and kind of I feel like one of the earlier dance weeks that I got to call, so it’s been awhile, I’d love to come back.

Penn Were you on staff?

Mary I was on staff. I would have to go back in my calendar to find out when it was. .

Penn You know, you have to remember when you say it was a while back, you’re pretty young. So…it could be 40 years ago.

Mary Right. I would say it’s got to be like maybe 8 or 9 years ago.

Penn So I was not obviously programing, so I would not have known that. So I’m glad, you sort of got a sense of what the camp was about.

Mary Yeah, wonderful, beautiful location, beautiful dancers.

Penn The best thing about Lady of the Lake is there’s no bugs and no humidity.

Mary Yeah. So for us New Englanders, you know, that’s pretty dreamy.

Penn But thank you for what you’re doing. You know, as someone who, as I say, could have been a folklorist I really appreciate what you’re doing to sort of preserve this. But to ask questions that are not only of the past, but also the present and moving forward. So thank you for the opportunity.

Mary My pleasure, thanks for your time. I always feel very lucky that I get to have these conversations.

Penn That’s great, thank you.

Mary Thanks.

Thanks so much to Penn for talking with me! You can check out the show notes for today’s episode at cdss.org/podcasts.

This project is supported by CDSS, The Country Dance and Song Society and is produced by Ben Williams and me, Mary Wesley.

Thanks to Great Meadow Music for the use of tunes from the album Old New England by Bob McQuillen, Jane Orzechowski & Deanna Stiles.

Visit cdss.org/podcasts for more info.

Happy dancing!

Ben Williams The views expressed in this podcast are of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect those of CDSS