David Millstone started contra dancing with Dudley Laufman in the early 1970s and has been calling dances for forty-five years: contras old and new, squares from different regional traditions, English country dances, and plenty of family friendly events. He’s been on staff at dance weekends, festivals and weeklong camps from Alaska and Hawaii, Maine to Florida, as well as in nine countries in Europe. As a dance historian, he’s published, spoken, produced videos and created websites that celebrate different aspects of country dance and music. He served for 12 years, including 6 as president, on the governing board of CDSS.

David Millstone started contra dancing with Dudley Laufman in the early 1970s and has been calling dances for forty-five years: contras old and new, squares from different regional traditions, English country dances, and plenty of family friendly events. He’s been on staff at dance weekends, festivals and weeklong camps from Alaska and Hawaii, Maine to Florida, as well as in nine countries in Europe. As a dance historian, he’s published, spoken, produced videos and created websites that celebrate different aspects of country dance and music. He served for 12 years, including 6 as president, on the governing board of CDSS.

Show Notes

Sound bites featured in this episode (in order of appearance):

- David calling a variation on the dance “California Twirlin” by Janet Levatin at to the music of Nova at the Ottawa Contra dance on April 28, 2016.

- David calling the singing square dance “Deep in the Heart of Texas” to the music of the Stringrays at the 2013 Dance in the Desert weekend near Tuscon, AZ.

More from David

- David’s work as a documentarian is prolific! Be sure to check out these links mentioned in the interview:

- The Square Dance History Project

- A Hand for the Band

- Find MUCH more on his personal website

- David has also presented for groups all over the country, both in person and online. Check out these recordings:

- Country dance in Modern Times: Squares, ECD, and Contras in Post-WWII America

- Contra Dance in Modern Times: 75 years of change in post-WWII America

- Contra Chestnuts: A New Look at Old Dances

- Square Dance: An American Medley (for the Country Dance and Song Society)

Dance Notation

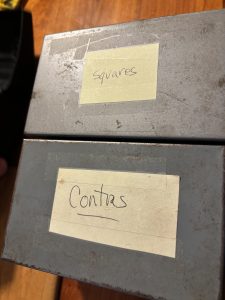

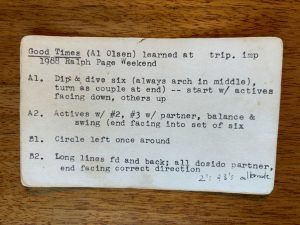

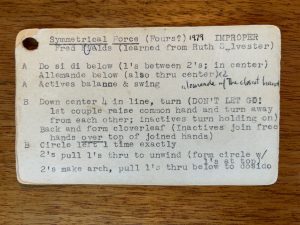

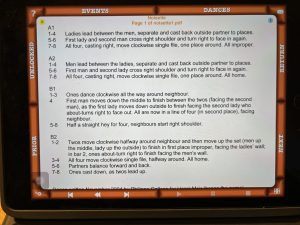

David has yards of cards (almost)! He uses “The Dancing Master” app to keep track of his English Country Dances and programs, but sticks with cards for contras and squares.

[ Click on image to enlarge ]

Episode Transcript

Click here to download a transcript.

Transcript – From the Mic Episode 22 – David Millstone

Ben Williams This podcast is produced by CDSS, the Country Dance and Song Society. CDSS provides programs and resources, like this podcast, that support people in building and sustaining vibrant communities through participatory dance, music, and song. Want to support this podcast and our other work? Visit cdss.org to donate or become a member today.

Mary Wesley Hey there – I’m Mary Wesley and this is From the Mic – a podcast about North American social dance calling.

David Intro

Mary Welcome back to From the Mic. This month I’m bringing you along with me to a cozy, snow-laden house at the end of a dirt road in the woods of New Hampshire for a chat with David Millstone. This is a house I visited over 15 years ago when I was first exploring the idea of becoming a caller myself. It’s always a treat to visit.

David started contra dancing with Dudley Laufman in the early 1970s and has been calling dances for forty-five years: contras old and new, squares from different regional traditions, English country dances, and plenty of family friendly events. He’s been on staff at dance weekends, festivals and weeklong camps from Alaska and Hawaii, Maine to Florida, as well as in nine countries in Europe. He served for 12 years, including 6 as President, on the Governing Board of CDSS. As a dance historian, he’s published, spoken, produced videos and created websites that celebrate different aspects of country dance and music.

David has spent countless hours documenting other people’s stories about dancing and dance history, so I felt grateful that he let me turn the mic towards him for a change. I hope you enjoy our chat!

Mary David Millstone. Hello. Welcome to From the Mic.

David Millstone Hi, Mary. It’s great to see you.

Mary It is great to see you too.

David Here we live an hour and a half away from each other, and we hardly ever see each other.

Mary It’s been too long, yes. There have been times when I’ve been on the I-89 corridor and driven by and waved in your direction. But this time I got to stop and come over to your lovely home. I’m always excited when I get to do these interviews in person which is not often. So grateful that that’s happening. I’m also having a lot of memories coming to your house, because it was one of the first places I came when I was a brand new, I wasn’t even a caller. I just thought…

David You should go talk to this guy.

Mary Yeah. Rebecca Lay said, “You should look up David Millstone” and you gave me a great pep talk, a great boost, lots of thoughts and ideas for me to go take away.

David And look at you now.

Mary So you are definitely a prominent figure in my origin stories and you are an amazing dance historian, documentarian. Does it feel different to be on the other side of the microphone here?

David Yeah, it’s fun. I was on New Hampshire Public Radio a month or two ago talking about this new project that we’ll probably talk about. I commented to the woman [Katie McNally] running the interview, “You do interviews well.” And, you know, the part of my brain that knows that you ask a question and then you just shut up and you let the person talk and you keep shutting up, and you nod—just as you’re doing now and you’re not saying anything. It’s all the things I learned from not doing them.

Mary The tricks of the trade. Well, I am excited to get a little bit more into your personal background as a caller, which I know some of. But often we’re talking about other callers, you know, people who’ve influenced the style over time. That’s usually where I start in these interviews is kind of to go back and ask, where did it all begin for you?

David I knew none of this stuff as a kid. When I was a kid, I had the obligatory piano lessons. The first piece I played in recital was “I Can Play With the Metronome,” and I’m told that what I did is I went up and started the metronome and it went click, click, click and boom, I was into it. My teacher told me afterwards that, “You know, you can let it go for a while while you adjust yourself at the bench.” Anyhow, in high school, a family friend came to visit and he played guitar and sang folk songs, mostly songs from the American labor movement, my dad was a union organizer. And so I was in high school, and this guy came with a guitar, and I thought playing guitar was pretty cool and so I learned to play guitar and in college I was playing sort of generic folky stuff and had a radio show on the campus radio station, “The Ethnomusicology Hour” where I played old bits of folk music and then moved to New England, moved to New Hampshire in 1972.

Mary Where did you move from?

David Well I had lived, after college, I had lived in Chicago. I had lived in Denver, I lived in California. I traveled to Mexico, got sick, came back and stayed with my parents in Pennsylvania, which is where I grew up. And then a friend from New Hampshire, a college friend, came down and picked me up. I arrived early January of ’72, in the middle of a snowstorm and it felt right. I had loved being in San Francisco, I mean, how could you not like living in San Francisco? I had a job, blah blah blah and you could do anything, any time of year, if you wanted snow, you could go to the mountains. If you wanted the ocean, well, you could just ride the trolley to the ocean. But, it was when I got here in the middle of a snowstorm that just something rang deep in my heart, and it felt like coming home in a way. I grew up in north central Pennsylvania, where as a kid, if there was a lot of snow it would be up to my calves. Well, I’m a lot taller now, so to be up to my calves, you have to go to New England. Anyhow, I came for what was going to be a two week visit, and that was in January of ’72 and here I am.

In that first winter, some friends up here dragged me to my first dance. I’m sure it was a Dudley dance, Dudley Laufman,somewhere in the Concord area. I can’t tell you where where it was, and I loved the music. I just was caught up in the music. A woman came up and asked me to dance, and I feigned a leg injury because I was so embarrassed. I mean, there were kids in high school and college, you know, who were dancers, and it wasn’t me. So I got through that first evening without having to dance. And then, later on, housemates of mine took me to a dance, another Dudley dance, this time in South Stratford, Vermont, which was the regular local dance that Dudley did with his wife at the time, Patty, once a month, and I fell down the rabbit hole.

It was initially the music that I just loved, the sound of the music because I was already playing, I was playing in a generic folky band up here as the years went by. But, unlike rock and roll or swing where you needed to have certain moves it was the appeal of someone telling you what to do. A very common, very common phenomenon and early ’70s the vocabulary of what to do was a lot smaller than it is now. I mean, you could be an experienced dancer and you would know 20 moves. And so I danced at that dance regularly and moving into the ’70s, there started to be other dances around here that I’d go to and became a pretty serious contra dancer with some squares mixed in and also whatever came along. I mean, the dances back in the day were wide ranging. So you’d do contras and you’d do squares and you do Sicilian circles. I learned Doudlebska Polka, which is a Czech folk dance, and I learned Levi Jackson Rag and just this wide variety of stuff. And of course, that’s part of what’s shaped my way of looking at things to this day, that kind of variety makes for a much more interesting evening. So that’s when I started dancing.

I was playing in a band up here in the ’70s called Sugar Maple. I was playing mostly guitar, but a little electric bass, and had built a hammered dulcimer. So I was playing dulcimer and we’d get hired to do parties. This was generic folk music, everything from bluegrass covers to old time to jug band to whatever. But any time we played something that was kind of upbeat, people would start yeehaw and stomping and elbow swinging and at a dance New Year’s of ’76, the people who hired us said, oh, and could you teach some dances? So I went to a friend and got a couple dances and taught some dances and it’s been downhill ever since.

Mary Downhill?

David Right. And then in 1980, there was a band called Northern Spy that was starting up, and they asked whether I wanted to call dances with them and so in November of ’80, we had our first dance. There was another guy in the band, Geoff Lamdin who played banjo and called, and I played hammered dulcimer and called. So he’d call for the first half and I’d play and then we’d switch roles. After about a year, he decided he’d much rather play than call. At that point, I pretty much put the dulcimer away. I knew I could either work hard at the dulcimer and become a mediocre dulcimer player, or work hard at the calling and become a competent caller. And so for five years, I didn’t touch the dulcimer, and I’ve really never have picked it up since and so Northern Spy and I ran this monthly dance for 35 years until 2015.

Mary In Norwich?

David We started at the Carter Community Center in Lebanon, New Hampshire and the very first dance, the band outnumbered the dancers. We had 14 people in the band, and so some members of the band would get down on the floor to fill out the hall. And then after, I don’t remember, a month or two, we moved. We found a hall in Etna, New Hampshire, in a lovely little church hall, and we had the dance there for many years, and it was a hall that worked well when there were 50, 60, 80 dancers but we were getting up to 100, 120 and there was no room and at the same time the church also wanted to reclaim the hall. So that’s when we went looking and then we moved to Norwich eventually and the dance is still going on in Norwich. So second Saturdays of the month, for many decades I was the caller and Northern Spy was the band. There are pluses and minuses to that sort of arrangement so that’s where I developed my contra calling chops.

Mary Was it common at that time for a band and a caller to work together as a team? I know Dudley had Canterbury Orchestra.

David Dudley, he’d hire two people, he’d hire a piano and a fiddle, and then anyone else was welcome and that’s what led to that huge exodus of the diaspora of contra dancing, all those people who had played with him. In New England, there’s, I think, an old model of a band owning a series. And you still see that, Wild Asparagus has their series. The Lamprey River band still has their series down on the seacoast of New Hampshire, Northern Spy had its series. The model elsewhere and now the model most places today, I think, is you have a committee running things and they’re bringing in bands and talent. Certainly, traditionally, there’d be a square dance caller who would have his band. It was almost always his band…and Frank Fortune had his band and Willie Woodward had his band and so on. So, I think back in the day, that was pretty much the case, it was pretty common. Today, I think it’s much more rare.

Mary I imagine as it’s something that you’re learning to do and working at as you’re describing that maybe having that one consistent factor of working with the same musicians regularly could give you a baseline.

David It’s really helpful. Yeah. You can write notes on your card, this dance goes really well with this tune and we know, blah blah, blah. Joys of Quebec works really well here because there’s a balance at the start of the B, just when the tune [sings tune] and so you make notes like that, as a caller. It’s wonderful to have your own series because you’re not just thinking in terms of that night. You know, we all as callers you know, I’ll do a chain here, a ladies chain, here in the evening and later on, that’ll just be something that everybody knows and we add to it. But you can think in terms of a series, you can think, oh, I’m going to do this figure and then next month I can use that figure in a different way and two months after that I can do this dance. And there’s the people coming, know who you are, they know what to expect, for better or worse and presumably, if they keep coming, it’s for better so you’re a familiar figure. It’s fun to work with the band, figuring out what’s going to work well together. You know what the band’s strengths are, and you can play to that. And so as you know, one of the caller’s jobs is to make the dancers happy, and the other is to make the band sound good.

Mary I wonder if you can talk through a little bit about your process of learning to become a caller, were there any aha moments, stumbling blocks?

David Oh, lots of stumbling blocks. Starting in the seventies and then especially in 1980 when I started doing this regular dance, there was another caller in the area, a woman named Ruth Sylvester, no longer with us. Ruth and I were both sort of getting started as callers at the same time. I don’t know that we ever made a formal agreement, but basically we ended up coaching each other. She’d come to my dances and I’d go to her dances and we’d give each other feedback like, “You know, were you aware that the first three dances in a row all started with neighbor do si do or balance and swing your neighbor?” “Duh, no.” Or things like, “When you said ‘la la la la la’ we had no idea what you meant. But then you said blah blah blah, and it was like ‘Aha!’ ” So you take your card out and you write a little note to yourself, and you change the wording on the card, so that was really helpful.

Ruth and I were both starting out learning to do this, but she had a much longer history. Ruth was going to Pinewoods, her mom was a Pinewoods person back in the ’40s so she had this long history. But as a caller, it was new for her as it was for me. So getting that kind of peer to peer support, sort of, as you did up in Burlington with your callers collective, where you were all sort of equals in the process, helping each other through it.

My first caller was Dudley so obviously I picked a lot up from Dudley. The example I always use, there was a time in my calling where I’d say something like, “Everybody swing your partner.” And at the same situation Dudley would say, “All swing.” Everybody swing your partner, eight syllables; all swing, two syllables, just cuts through the chatter, the clamor, it just cuts through. Dudley had spent years working in schools 180 days a year without PA systems. So he had learned to hone things to the bare bones of what was needed. That was really important for me to learn. As a dancer, I really appreciated callers who could explain things precisely and quickly. Because I was young and hot to trot on the dance floor and standing there listening to someone go on and on and on and on and on and on and on and on, like, “Come on, we want to dance! And so when I became a caller, both for contras and squares, and then particularly when I moved into English dance, that was high on my list of something I wanted to bring, I wanted to bring contra dance brevity to my presentations at the mic.

Then in the late 1970s, we invited Ted Sannella to call our local dance. There was a dance that was being sponsored by Muskeg Music, which is still running the monthly dance in Norwich, and we invited Ted to come up and he did a caller’s workshop, and there were three of us who attended, Ruth, myself and one other guy, and we had a full hour and a half caller’s workshop, I still have the notes. Meeting Ted was this eye– opening experience. Dudley called a relaxed evening, that was his goal. It was a party, he just sort of hung out and so the model that I had, not just from Dudley but from other callers in the 70s, was they’d call the dance and then there’d be 3 or 4 or five minutes, they’d be either mentally or physically shuffling through their caller’s box of cards and you were talking, and it was a very social occasion. Ted came in with his program written out in advance, with the alternates picked, alternates that were a little more challenging and alternates that were easier to plop in with the tunes already selected based on having listened to the band’s recording or looking at their tune list, it was like, “Oh my God.” Ted was a pharmacist, he was organized and it was a completely different model.

And of course, as a dance leader, he was extraordinary. To this day when I’m up at the mic and something happens…,you know, the WWJD, what would Jesus do? I have the “WWTD,” what would Ted do? Ted’s workshop was the first time I heard of the KISS principle. You know, “Keep it Simple, Stupid.” There’s always that moment as a caller where you’re up there, I’ve got this dance, it’s a little bit harder, but, oh, they’re going to love it. And this dance, which I know they can do, which is easy and if you’re in doubt and you pick the easy one, you’re always going to be safe. There’s always that part of me, oh, but I can teach them this one and sometimes I can and sometimes I can’t and it’s like, oh, Ted.

So Dudley and Ted were really the two main influences and in some ways Larry Jennings in a different way but that’s a whole other thing. But those two, really, I think shaped my calling. I mean, from Dudley, that whole sense of, it’s a party, it’s fun and precise, barebones instructions and from Ted really thinking about the evening as a whole, figuring out what figures you’re going to introduce, where, when you introduce variety, when you put the squares in, when you do the mixer, how you follow a complicated dance with something simpler or completely wacky. Yeah, I miss him.

Ted is the person in many ways, in a roundabout way, responsible for my becoming an English caller because he and Jean would come and do dances here, and he’d stay with Sheila and me and Ted for years would say, “You need to go to camp, you need to go to Pinewoods.” Then in 1987 he said, “David, I’ve been talking about this enough with you. You need to go to Pinewoods and you need to go this summer.” And so, okay Ted, yes, sir. So I looked at the list and there was this thing called English and American Week. Friends, Ruth in particular, had been urging me to go to Pinewoods for years. But she didn’t have quite the same standing. A few other people said, “David, try English, you’ll like it.” I tried it. I didn’t like it. I tried it again. I didn’t like it. There’d be sessions somewhere, you know, a special event of English country dancing for contra dancers. I went, nah. So I looked at the roster for Pinewoods, and there was English American Week and being a hardcore, snooty contra dancer, I said, “All right, well, I can go, I’ll do the American dance. I’ll show people how to dance, I’ll have a great time and I’ll put up with this English stuff and get through it.” There were two moments during the week, one was in dancing Well Hall and one was dancing Mad Robin where I had those aha moments, “Oh, that’s what this is all about.” That’s when I fell in love with English and then later on started calling it. So Ted was the one who got me to Pinewoods and without that, I probably never would have gotten into English.

Mary And at this time, when you were building up your skills as a caller, experiencing different styles, do you have a sense of how you saw yourself and kind of what your aspirations or drive were?

David No, I just wanted to call. I mean, I had this local dance and it was great fun. It was something I did every month. At that time, I wasn’t thinking beyond that. I was very happy, I did parties, I did weddings, at this point I’ve done, God knows, hundreds of weddings. I did some family dances, sort of school stuff. You know, I was a schoolteacher, and the school I worked in, Norwich, had a very strong music program which included dance. So I would teach Haste to the Wedding and the whole school and parents, we’d have 400 people on the green in Norwich dancing Haste to the Wedding around the tree that used to be there as part of our May festival, and I coached sword dancing as part of the Mummers play for our Christmas show. But no, I was very happy doing that. And then, probably late 80s into the 90s I was thinking, “Wait a sec, all these people are getting hired for camps. I’m not getting hired for camps. Why not? I’m a good contra dance caller.” And so I did a little introspection and pulled out my latest copies of the CDSS News, I joined back in ’87 when I went to camp, because I learned that that’s the way to make sure you got into camp was to be a member. And so I turned to the back and looked through who are all the people on camp? Oh, well, Steve Zakon-Anderson is there, ah Steve calls contras, Steve also teaches waltz, and he can teach, vintage dance of some kind or tango, something like that. Lisa Greenleaf, oh, Lisa also teaches squares. So and so, oh, they also… and I realized if you call contras and that’s all you call, you’re not going to get hired for camp, you need something else. And so I thought and said, well, I’m going to become an English caller. I looked around, there weren’t many people at the time who did both. Brad Foster, of course, Scott Higgs, handful of others, Susan Kevra, a couple other people, but not many. And so I said, I’m going to develop English. So in ’93, I started calling English and sure enough in time…I mean now I get hired probably more to call English, but being able to do both and squares, my love of squares has only strengthened in recent years, so you never know where it’s going to take you.

Mary No. Absolutely.

David Like, stay open to what the universe hands you.

Mary So you described your introduction to dancing, coming to Dudley Dances where there was a wide variety of figures and styles happening on the dance floor. When you started your dance with Northern Spy I imagine it echoed that same…

David Yeah. I mean, that was 1980. the repertoire was starting to expand, but up here…I wasn’t going down—I don’t remember the first year I went down for NEFFA, but I wasn’t part of the Boston scene where Ted and Tony Parkes and Tony Saletan were actively calling, and Ted was dramatically changing the the landscape of what was possible in the contra dance world and all of them, Tony Parkes and Ted in the square dance world. But yeah, I was calling mostly contras and some New England squares and mixers. Both Tony and Ted were big on having a mixer, third dance of the evening, you don’t do it first because there are still people coming in. You don’t do it second because there’s still people coming in. You don’t do it fourth or fifth because by then people have sort of figured out who they want to dance with. But third dance of the evening is a great place to put a mixer in, and circle mixers add variety of formation and something different. And so that became just a feature of what I would do.

As years went by and I started to travel and go to NEFFA and pick up dances, and at that time, of course, picking up dances, you’d be someplace, someone would call the dance and you’d immediately scribble it down. You know, now people come up and say, “Can I get that dance from you?” and I’d say, yeah and they take out their phone, take a picture. The whole business of writing down a dance, it’s like, oh, that’s so archaic. So, yeah, building up a repertoire. At this point, I’ve got, well, I can show you, I mean probably a yard’s worth of index cards, most of which will never get called. How many dances do you need? And the same thing with family dances, I mean, there’s always more and more dances. For family dances, people say, you know, I need to build up my family dance repertoire. I say, how many do you have? They say, I’ve got maybe 15 or 20 that I can call really well. I say, you don’t need any more than that. But I think many callers, myself included, have a collector’s mentality and, you know, “Oh, that’s a cool dance, let’s do that.” I’d love to be able to go through and winnow. So how many dances do I need with this particular one? Oh, there’s got to be one that’s like the best and just stick with that. At this point, there’s a small subset of dances that I use over and over and over again. I remember George Fogg, the great English dance leader from the Boston area I said, George, how do you set your program for your various dances? He says, well, I figure out for this year, this is what my program is going to be. I said, what? He says, well I can do that, I’m teaching in Texas and then I’m teaching in Kentucky, and then I’m teaching here and there, he says, so I have my program for the year, and it was like, whoa, what a concept.

Mary I love that.

David Yeah, and if you’re traveling around a lot you can do that.

Mary If you’re calling a local, your own local series every month, not so much.

David If you’re calling your own series…Well, especially in the contra dance world, as people, back in the day, sorry, I need to change my voice [imitating an “old-timer voice] “I remember, back in the day,” because the repertoire was so much smaller when I started in the ’70s. It was the Chestnuts, and occasional dances from Ted or Tony that had worked their way into the repertoire, but that’s when I started out. And yeah, so if you did Chorus Jig every month, people were like, oh yeah, we know this dance and that’s certainly the traditional square dance people. A given caller would have maybe 15 dances in their repertoire and that’s what you’d dance. Now there are serious dancers who want something new and different all the time. I think Dudley has called it the consumer mentality and you start to see that. Mary Dart, in her contra dance choreography thesis goes into the difference between a community dance and a dance community. At a community dance, you can call the same dances over and over, and people in the community know them and like them and the dance community is a much more self-defined…people who define themselves as dancers and that’s a part of their identity, as a dancer and they’re looking for something different.

[ David calling a variation on the dance “California Twirlin” by Janet Levatin at to the music of Nova at the Ottawa Contra dance on April 28, 2016. ]

Mary Did you witness that shift from community dance to dance community at your dance locally?

David Yeah, ours has more of a community dance feel. Again, I think part of it was it was just the same old band. It was the same local band and the same same old caller getting older. I remember one guy coming up to me saying, this was a fellow who had started at that dance in Norwich, and he came up and said, “This is the last dance of yours I’m going to come to. Yeah, I’m going to go down to Greenfield on a Saturday night, you’re too friendly to beginners.” I thought, okay. He had moved, that was a change. Someone who came, who got pulled in from that welcoming community, simple dances, starting out the evening and gradually working up to a little bit harder and then fading off. But he had gotten to the point where he was, that kind of a dancer who wanted the challenge. And I said, well, sorry we’ll miss you, but I’m thinking I’m not going to miss you at all with that attitude. Dick Crum was an international folk dance leader and taught a lot of Balkan dance, and he has a classification of dancers in it, it’s like four levels. One is a beginning dancer, knows nothing, intermediate dancer, knows everything, too good to dance with beginners. Hot shot dancer knows absolutely everything, too good to dance with anybody and an advanced dancer, knows everything, dances with anybody, especially beginners. A lot of people get stuck on that level two or level three. I went through a period of being a hot shot dancer. So that was the attitude when I went to Pinewoods in ’87, that was sort of the attitude that I was bringing with me. And then you realize the joy of getting new people out onto the dance floor and having fun and making them have fun.

Mary Yeah. As you’ve seen, the variety of dance experiences that are available to people just kind of widen…and it seems like you choose your path through that of where you want to kind of put your energy and your time. I definitely have experienced you as a champion of keeping those connections to the roots, to kind of the history and enjoying the stops along the way. That Petronella used to be this chestnut that was done to the tune, the same tune and then the same way. But then you’ve really done a deep dive on sort of tracing all these little steps in the evolution of choreography, of music. Where did that interest of…I mean, I really see it as like a historian‘s approach to dance traditions and dance culture. Where did that come from?

David In part, I think it’s because I started when I started and where I started. So I started when the repertoire, the contra repertoire was a traditional repertoire so that’s in my bones. Over the years, of course, as that has faded or in other parts of the country where it never existed, it’s part of me, so obviously it’s important to me. I think it’s also dancing in New England, the line that I often use is, you know, we’re dancing in church halls and Grange halls that have held dances for 100, 150 years. When you’re dancing. Chorus Jig in a Grange hall, that dance has been done in that hall, to that tune so many times over the decades, we’ll say decades, over the centuries, at least a century. I like to think that there are dust motes floating around in the air that still carry the vibrations of it. So when you’re dancing a dance like that in a place like that, it’s like the latest incarnation of keeping that tune and that dance alive. I mean, that sounds a little mystical, and I’m not a very mystical person, but, when I dance some of the older dances in these older halls, I really feel a connection with dancers who have come before me.

I love a lot of the new stuff that’s being written, and I call a lot of it. I think a lot of people say, “Oh, David, he just calls the old stuff,” and I would like to say that I call a lot of pretty cool, hip, new dances. But I also like the older stuff. I’m aware as I travel when I’m on staff at camps or calling a dance somewhere far away, that other places who don’t have that rich tradition that we in New England have, they’re not drawing on that. I remember Ernie Spence and his wife Joan, who were mainstays of the Boston scene for years. They’re the ones who took Kate Barnes to her first dances in the back of their station wagon. Ernie and Joan, years ago, were out in California visiting a relative, and they decided to go to the local dance. And the sweet young thing taking admissions saw this older couple come in. Now, Ernie and Joan had been dancing since the ’40s. They started with the Methodist World of Fun series and they danced regularly with Duke Miller and with Ralph Page. So they walk into the hall and they pay their money, and the person behind the door treats them a little bit…. you know, it’s this older couple, “Well, what we’re going to do tonight is called contra dancing and there’s going to be a caller teaching it.” And they’re just, “Oh yeah, yeah, is that so? Oh, okay.” And then since they were there early, the host took it upon herself to teach them a little bit about the background: “So what we’re doing tonight is called contra dancing. It’s a dance form that was invented in California about ten years ago.” And they’re there, “Oh, is that so?”, just sort of nodding. So you’re aware that there are places where this is all imported, especially contra dance. I mean, square dancing has far deeper roots throughout the country but contras is a relatively new phenomenon.

I did a project where I was tracing what I ended up calling the contra dance diaspora. How did contra dance spread throughout the country? That was collecting stories from people all over and I’ve looked at the changes in choreography and how that relates to the change in society and the way the dancing is. I mean, when you look at Ralph Page’s books, he’s talking about longways, 6 to 8 couples. Well, you can have a longways dance that’s 6 to 8 couples and it can be very unequal. Money Musk, classic case, it’s a dance for the ones and if you have 6 to 8 couples, everyone can get to be a one. But as you get to the ’80s and dancing starts to become much more popular and people are discovering it at festivals and there’s 30 couples in line, if you’re the last couple in line in 30 couples and the dance is Money Musk or Chorus Jig or Rory O’More, very unequal dances, you’re never going to get to do the cool stuff.

So choreographers start to change the dances that they’re writing. Gene Hubert is a classic case. Start writing dances that work to keep everybody active and the dance shifts. People start going to dances for different reasons. At your community dance back in the day, back in Dudley’s day, Dudley always laments that there’s not farmers and truck drivers and mill workers coming to the dances. I keep saying, Dudley, we don’t have truck drivers and farmers and mill workers. People are now information workers coming to dances. And so back in the day, people didn’t come to a dance to get their exercise. Their daily life was filled with hard physical work. Dance was the social occasion, which is why in Nelson, up through the ’60s, men would come to dance wearing a dress coat and a white shirt and a tie and dress up to go to the dance and then the hippies showed up and everything changed. Now people come to dances with three changes of t-shirts and their sweat bands and their running shorts, they’re coming to get exercise. And yeah, it’s a much different environment than going to the gym.

So looking at how, when I started, there were maybe 20 basic figures, and if you knew those figures that would carry you through five years of dancing. When I’ve made lists more recently there, it’s more like 40 to 45 figures. So the dancing, the choreography has changed, the social norms have changed. We never used to have beginner sessions. The callers would program really simple dances at the start and you’d learn what you needed.

Mary You’ve never struck me as a preservationist as wanting to continue for the sake of form. You’re much more interested in the dynamic processes and how and why things change and continue to.

David I interviewed Kitty Keller once. Kate Van Winkle Keller, who was an extraordinary dance historian, and she really made the point that dance doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s a social construct and the kind of dancing you do reflects the society in which it takes place. The dancing that we did in the early ’70s reflected that society, it reflected the whole back to the land movement, the hippies. It reflected Dudley and his personality. The dance scene today is very different, reflecting a different world. People coming to dances back then, a lot of the guys were carpenters, because that’s what, you know, was part of that whole country living. A lot of the people coming to dances now are IT people, and they are used to using their brains in interesting ways. So dances are more complex, much more interesting to people who are brain workers, and who also want to get exercise, so get physical stimulation and mental stimulation so yeah, dance doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

Mary You, I think, have, it’s safe to say, a particular love for square dancing.

David Yeah, well, I love them all. I love them all. I did this project collecting histories of contra dancing, and so that was basically from 2000 to 2010. So I ended up with 450,000 words, 800 single spaced pages of stories that I had collected, mostly through email, and that came out of making the films. I did the film about McQuillen [Paid To Eat Ice Cream]and then a film about Dudley [The Other Way Back], and there’s all these references to Ralph Page and trying to get stories about Ralph Page. A lot of those people are no longer alive and even at the time were no longer alive and part of me said, “Well, I’ll keep trying to collect those stories but at the least I want to leave a good record of my generation.” You know, the boomers because we’re the ones who created the contra dance boom, the Dudley expansion. So that’s what led to collecting all these stories about contra dance diaspora and how did contra dancing get out of rural New England and become this phenomenon across the country? So writing people and collecting the story, doing oral history without having to do transcriptions for the most part, it was great. I mean, occasionally someone would send me a letter, John Shewmaker out in Saint Louis probably sent me an 18 page letter so I’d have to type that in but most of it was just email. I’m thinking that somebody at some point is going to want to write a history of this whole movement. Mary Dart has her thesis and it focuses on choreography, but it’s related to changes in society. But I knew that whoever eventually was going to write that history needed more than membership lists from CDSS. And so my line was, “Let’s collect the stories before we all end up in the Alzheimer’s units.” That was a very fulfilling project. CDSS has a copy of that material, and the University of New Hampshire has it, I add to it occasionally, but after about ten years, I figured I’ve got a lot here.

And that’s when, let’s see, somewhere in there, I made the film about Ralph Sweet [Sweet Talk]. I had interviewed Ralph, not with the idea of making a film, but just because he was getting on and his was an important voice. In the course of making the film about Ralph, it was a way to talk about square dancing, because I knew enough at that point to know that squares were far more important in American social dance history than contras were. Since Ralph was a square dance caller, a modern square dance caller for 20 years, as well as a contra caller and lover of traditional squares, it was a way of inserting that material into the Ralph video that would be seen mostly by contra dancers. I mean, contra dancers go to NEFFA and they get very excited. There’s 400 people lined up for the contra medley and it’s like, wow, this is such a big thing. I remember talking to Bob Brundage, long time square dance caller, he said, “I remember being at the such and such place in Nebraska, and the band and I were backstage and the curtain opened up and we were ready to dance and then I looked out at the hall and there were 800 squares, all lined up, just ready to go.” and I did the math, 800 squares. It was one of those moments where you just realize how big square dancing was.

So in 2010/2011 is when I started the Square Dance History Project [ https://squaredancehistory.org/ ] with the idea of just trying to collect material about the history of square dancing, because there were a lot of square dance histories online that were pretty bogus. You know, it goes back to Morris men and ritual sacrifices around sacred wells in England and it’s like, come on. I also knew that the best way to look at a dance form is to see it. Trying to write about square dancing, yeah, you can say things, but the best way is to see it. So the primary goal in the early years was to collect moving images of square dancing and from the beginning I was interested in presenting a wide view of squares, traditional squares, from all parts of North America. Modern squares, that whole modern square dance movement. The historical antecedents, quadrillies and cotillions that fed into eventual squares and collecting moving images and along the way, well, let’s also collect photographs and let’s collect audio clips, etc.. So at this point, there’s close to 2000 items in our digital library available to anyone who wants to see it and it’s a good thing. I think I’ve got a couple people who are agreeing to become administrators of it to keep it going. CDSS has agreed to continue the site so all those materials won’t go away.

I’d go to the Library of Congress and find videos and find material they had and go through all the permissions and digitization etc.. So we have some materials on there that are really wonderful to see. I go to it all the time when…how does this square go? Oh right, I’ve got that on the site and oh this is how Jonesy called it or this is how Dick Kraus called it and then you get to hear Lloyd Shaw, so that led me sort of deeper into squares, I knew New England squares. 2011, we had a dare to be square at Brasstown, which was an extraordinary gathering. I had six guys as it turned out, on my central committee, I like to call them. I wanted people who were experts in different areas of square dance, and who had done research and published in one way or another. So I ended up with Phil Jamison and Bob Dalsamer, Larry Edelman, Tony Parkes, Bill Litchman and Jim Mayo. Jim, alas, no longer with us, he died in the last couple of years. Jim had started dancing with Ralph Page in the ’40s and then went over to the dark side and became an early modern square dance and was the first chair of CALLERLAB and was on the CALLERLAB Board of Governors for 40 years, probably something like that. So CDSS provided some extra money, and Brasstown, John C Campbell Folk School provided the rest, and all six of those people were at Brasstown in 2011. CDSS provided money to hire a videographer and we hired John-Michael Seng-Wheeler, a young dancer who also was a skilled videographer.

John-Michael said, “So what do you want me to do?” I had already read a talk that Mike Seeger gave about the film that he made with Ruth Pershing called Talking Feet. And Mike said, “When you’re filming an individual dancer like a clogger or a flat footer you show the whole body, head to feet and you just show it. And when you’re showing a figure dance like squares, you show the whole square,” and that’s it. John-Michael has made some amazing videos, his videos of the Great Bear Groove are among the absolute finest examples of the excitement you get at being at a hot contra dance. I was there calling one year and we did the same dance, I think, three different times throughout the weekend so that he could film it from different angles and edited it together just beautifully. I said, “John-Michael, I don’t want you to do any of that. I just want you to find a good square and stay on them” and he’s a good enough dancer that he could realize right away, “Ooh, this square’s having troubles” and he’d pivot and get a square. We have 100 videos from Brasstown 2011, something like three quarters of the people who came to that weekend were callers. So you get to see, if you will allow me, some of the creme de la creme of the calling crowd and you get to see some of them make mistakes. There’s one wonderful sequence where Tony Parkes, who is an extraordinary caller, is out there dancing, and he’s confused. It’s like, yes, it happens, it happens to everybody.

You get to see all these dances from different traditions. I mean, Bob and Phil are calling dances from Southern Appalachia, Bill Litchman is calling dances from the southwest. And in particular, for me, being exposed to more dances from Southern Appalachia was a real treat. I had read about the dances, but actually getting to dance them, it’s like, oh, this is fun. So every so often now I get to call dances with a band that is an honest to goodness old time band. What I loved, the first time it happened, I found the music unlocked a little door in my brain, and my mouth started coming out with all kinds of patter that had never come out before. You know, “Promenade your partner round, make that big foot jar the ground” had never once emerged from my mouth when the band was playing Saint Anne’s Reel. But when they’re playing Yellow Barber or, you know, some other classic Southern tune, it’s just because listening to these dances over the years, that patter was associated with a certain musical sound. So that’s been really fun. And now with this series that I’m calling in Plymouth, New Hampshire, which wants traditional northeastern singing squares, I’m getting to call all these dead simple, lovely singing squares and having a great time.

Mary I love it. I love it. I have spent a lot of enjoyable hours scrolling through that site. It’s just a treasure trove and just the fact that it’s just available online, that’s just wonderful.

David Yeah, and you do it because A- it’s useful, but mostly it’s so satisfying to learn all this stuff.

Mary Yeah, it enriches it so much. Just hearing about all of these, these different settings, in which you’re calling and making dance happen and all these different perspectives you have on it as a caller, as an organizer, historian but I wonder if you could just talk a little bit about what what is it that the caller does and what are kind of some of your core tenets and, and principles that you have come to hold as a caller over the years?

David Well, Ralph Page said, describing the caller, he said, “The buck stops here.” And so, I feel that—that you are the person in charge of sort of orchestrating the whole evening and making sure that that it works, that the dancers have fun, that they’re successful, that the new dancers feel welcomed and the experienced dancers have something to challenge them, or that they can go away feeling like they got their money’s worth. That the band can shine to its fullest so that they’re not being forced into awkward boxes and that I can have fun up there. So I think of Tod Whittemore, who doesn’t want to call if he can’t do singing squares. I mean, it’s like that’s what gives him pleasure and if he can’t have fun as a caller. So I don’t want to be in a situation as a caller where I’m not having fun. I’ve turned down some gigs where there was a band that was playing that’s a perfectly good band, but I did not like their music. So I don’t want to be on stage for three hours or for a weekend with the band, whose music I don’t particularly enjoy. Other people love that band, that’s great. So making sure the musicians are going to have fun, the dancers are going to have fun and I’m going to have fun, that’s important. I want people to come away feeling that they’ve had some things that they’re very successful at. I’m not averse to throwing in a challenge here or there. I like to have variety in programs. If I’m hired to call an evening or a weekend, that’s all contras, I can do it. I’d much prefer organizers who say, yeah, we’re open to you calling this. I mean, the Belfast, Maine, dance is a wonderful example where they have their expectations really clearly spelled out. “We would like mostly an evening of contras, but we’re certainly open to you calling some other things in the course of the evening.” I love it when I’m working with groups that have thought about what they want and are able to explain that so clearly. It’s really harder to walk in and someone just says, “Well, you know, we want you to call an evening of dance.” Well, what do you want? I like being able to include squares. If it’s a mostly contra crowd, I won’t presume to do lots of squares, but I’d like to include that. I like to have a mixer. I like to be able to feel that I can throw in some oddball little dance, a five person dance, or a five couple dance or something like that. So within that, I try to learn as much as I can about who’s going to be on the dance floor. You know, you talk to callers who have worked with that particular group, and you try to come up with the program that is going to have something for everybody.

Mary Are there any things you would say are difficult or challenging in taking that role as the caller of having the buck stop with you?

David There are occasionally places where people expect the caller, this is rare, but they want the caller to deal with discipline issues. Ralph Page used to do that, he used to kick people out of the dance floor. You know, “You in that square, you’re doing it wrong, get off the floor.” You know, I’m not going to do that. But there are places, rarely, now, I think most communities really thought about this and understand that if there are issues with the standard ones, creepy male dancers who just don’t respect their partners or neighbors boundaries, it’s not the caller’s job I hope to deal with such people. That’s the committee’s job. But I think increasingly in the last, I don’t know, 5 or 10 years, dance communities have recognized that they have a responsibility to find good ways of encouraging good behavior and dealing with individuals who don’t conform. I remember in Norwich we had a dancer who kept violating the boundaries, and we finally told that person, no, you’re not welcome here anymore and then they moved to another community and we heard they were doing the same thing elsewhere, it’s hard. We’re such a warm, open, generous, welcoming community, but we need to be safe and that’s on the organizers. So the couple times where I’ve been in a position where people were expecting the caller to deal with that, as a visiting person coming in, that’s not a reasonable expectation, that was uncomfortable.

Mary Yeah. That’s hard, and it’s also, I think it’s a question of what’s feasible if, I mean, the caller is juggling a lot of things. I also really appreciate, like you were saying, communities who have thought about this and articulated and formed some really clear sort of systems and procedures.

David Guidelines, you know, signs up in the hall, buttons identifying the committee, blah, blah, blah. I mean, all of that now is much more common.

Mary Being able to clue the caller in to the existence of those systems and have them be a part of it, you know, I was just at the BIDA the dance, and they have a very clear system that I can help reinforce from the mic, because that is one thing about the caller is as I have often said, you’re the loudest voice in the room. You’re kind of the main focal point at the times when you need to be and that can be a powerful way to kind of impart some safety messages and things like that. But you can’t be expected to then follow through and uphold them, so being able to identify those people is really helpful.

David It’s hard. I’m not out calling regularly on the circuit. I’ve never been a traveling caller. There are people, you’ve done some of that Mary, and there are other callers who are out there all the time, and I’ve never done a tour with a band where we sort of went around and for several weeks did things. One of the things that from time to time, you’re calling in a community that still has what is termed center set syndrome and that’s hard for me as a caller. If you have a group of dancers who are so caught up in their own personal experience that they have lost sight of the bigger picture. And so a hall where there’s a long and crowded center set and two short sets on the side, where the new people tend to end up, they need those experienced dancers with good attitude to help them for the long term, if for nothing else than for the long term health of the dance series to make it possible for those people who want to dance. But you can’t get preachy from the mic, you can encourage people to go and when people won’t move, and you have 20 couples in one set and five in another and five in another, it’s just really hard. It’s not often that I’m in communities where that’s the case, but every so often that happens and that’s hard. You asked what’s hard? That’s a hard one.

Sometimes what’s hard is being paired with a band, this doesn’t happen much now because I’ve gotten better about saying no, being paired with a band that really is interested in showing off what they do and don’t understand that you’re there for the dancers. I really believe that I’m there for the dancers and the band. I remember talking to a wonderful, wonderful band once, and I gave them the signal for two more times, and they shook it off because they had a three tune medley in mind that was going to be on their album, and they wanted to play each of the three, and they were wonderful musicians. They all were dancers, they knew how to choreograph the pulse, the rise, the fall, etc. but it was time to stop that dance and we had a discussion afterwards.

Mary Isn’t it so interesting, you know, it’s just such an interesting collaboration between the caller, the band, the dancers.

David The band wanted people to hear their cool…and it was a wonderful arrangement. I heard it when it came out on the CD, and it was a wonderful set, but it would have been nice if they’d told me beforehand. One of the things I learned is I need to check in with the band. Do you have something that you are committed to doing this time? So I could tell you, when we’re a third of the way through instead of half the way through. So you learn, and usually you learn by making a mistake, and you jot a note on your card or a mental note.

[ David calling the singing square dance “Deep in the Heart of Texas” to the music of the Stringrays at the 2013 Dance in the Desert weekend near Tuscon, AZ. ]

Mary You were telling me earlier about your most recent documentary project that you did, the contra diaspora, the square dance history.

David As part of that, I did a whole thing, there was no website for the Square Dance Hall of Fame. So I did a website about that. [https://hall-of-fame.squaredancehistory.org/] That was a fun project. My latest one, the one that’s just now hitting the streets, is a thing called A Hand for the Band, and it’s a celebration of musicians. [ https://ahandfortheband.org/ ] So I’ve done contra dance history and now square dance history and now it’s a look at dance history through the musicians. The criteria for being on this project were: you had to be a musician or a band who played for contra or square dances who came relatively early—and that’s a loose term—in the life of a particular community’s revival of dance history and who recorded. And the recorded part was in part…I mentioned earlier about the Square Dance History project, the importance of having moving images. Well, the same with a band, instead of just writing about a band’s music, I wanted people to hear it. So from the get go, the idea was you’d get to see an image of their first album. You’d learn who the personnel was and their instruments and what year and where they were. You’d have comments from musicians about the band, and you’d be able to hear an audio clip from a full track from their first album. It’s awkward because a lot of bands look back at their first album and are like, oh, don’t use that one, use our third album. But “consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” says Ralph Waldo Emerson. For the most part, the bands included in that, it’s their first album.

That started when I was giving these dance history talks, and I’d give them locally. I’d give them if I was on staff at a weekend or a week. And then during the pandemic, I was giving dance history talks online, and there was often a section, if I was focused on contra dancing, where I’d talk about changes in the music over time and the examples that I was drawing on were all, or almost all. New England bands, because obviously, what else could there be? If we’re talking contra dance history, it’s New England bands. As I’m giving talks to nationwide audiences, I realized maybe I need to spread a broader net. So I said, all right, well, this is me talking to myself, well, I know all the New England bands, which turns out not to have been true. But let’s see who else was out there early on, who played for dances and who recorded, thinking that I might find a dozen or maybe two dozen other bands. And by “early on,” it varies, because if you’re talking Boston area, there’s dancing there, certainly in the ’70s, if you’re talking in West Podunk, Nebraska, it’s a much newer thing. So it’s not an absolute earliest, it’s earliest for a community. So I thought, let’s see who I can find. I defined it as contras or squares. Because again, I think they’re both an important part of the mix. I went looking and as of today, mid January when the site is refreshed, we’ll have 300 bands on the site. I discovered this wealth of bands out there going back even into the ’70s, where I was thinking, well, it’s all New England. Well, it’s not, especially if you’re defining it as contras and squares, because squares are so deeply rooted in American society. So you have the Bucksnort Barn Dance Band in Gainesville, Florida, with a recording in the ’70s, and they were doing square dances down there, and you have the Deseret String Band out in Utah, and you have Cousin Curtis and the Cash Rebates in St. Louis, who are still playing for dances 50 years later. And so all this extraordinary wealth of material which is now available for people to see. So since so many of them, I was able to get in touch with people and have their comments. It’s another way into music and dance history. I mean, some of my favorite moments where I’d write someone and say, so I’m interested in this album you recorded 43 years ago, blah blah, blah. They say, how did you ever hear of that? I thought no one knew that album outside of this narrow area. I said, well, you know, people brought it to my attention and can you send me a clip from this and I’d love some comments and they’d say, jeez, I should talk to my bandmates. I haven’t talked to them in ten years. So they would reach out to their bandmates and they’d each send comments in.

So personally, it’s been this amazing education, and it’s given me a really deep appreciation of old time music. If you’re in New England in the contra dance world, you don’t get a lot of old time. In fact, Larry Ungar will talk about how hard it was for Uncle Gizmo to get hired as a band because they didn’t have a piano. They were getting hired in the South, where people knew Larry as a coffeehouse performer or Cathy Mason with the Dead Sea Squirrels, which is pretty much an old time band talking about some resistance in New England to that. Other parts of the country, the Midwest, old time, has been part of the contra dance scene forever. Dillon Bustin took New England contra dances with them to Bloomington and formed this unholy alliance because he wanted live music and all people there were playing was West Virginia or Southern Indiana tunes and so Petronella got grafted on to old time music, and you can see videos of people dancing Rory O’More to John Brown’s Dream. It’s this wonderful mismatch of dance and stuff, but that’s sort of my understanding is that’s still very common in the Midwest. And in squares of course, squares and old time music have such a long connection together. So it’s been fun learning about all that and then finding ways to share it with other people.

From the beginning, my vision, was that people would be able to look at this on a map, that they could search geographically by zooming in and search chronologically. I talked to a tech guy at Dartmouth who worked with me for a while, and he wasn’t able to find a good way of doing it. He said, well, what you really need to do is write a grant for $40,000 or $50,000, and that’ll buy you enough computing expertise to do this. I didn’t want to through a process like that. So I asked around in the dance world and a friend suggested Andrew Frock. Andrew’s a young guy, his dad’s a caller, his mom’s a fiddler. I’ve never met him. He’s a couple of years out of school as a computer science major and he said, oh, yeah, this sounds like fun. So he’s done the programing to make it possible. So a Hand for the Band.org is there and we’ll keep updating it. If people have other ones to add in. I heard from a guy in California, we’ve been corresponding, and he says, I’ve spent many hours down this rabbit hole but you’re missing so and so and so and so and so and so. So it’s been great. That’s exactly what we hoped when we made the site available that other people would say, oh, you should put so and so. And then people writing and saying, I think we should be there. Well yeah, you’ve got a band and you go back to, you know, 1993. It’s just that we have four other bands from the late 70s or early 80s in that area. So no disrespect intended, but we’re going to just stick with those because I’m not trying to showcase every single band.

Mary Right. You’re kind of looking at this snapshot of, the seeds…

Whoever was early in a particular area and the challenge is that some bands had been in an area of playing for 40 years and then finally got around to making an album. I mean, we all know that going into a recording studio, a lot of bands have fallen apart when they decide to make a recording. It’s a daunting task. So this is not in any way, these are THE important bands. Some of the best bands that people have spoken about never recorded. The band that was The Polecats, which was the house band for the Chicago Barn Dance, for decades, never recorded as that band so they’re not there. You’ve been in places, I’ve been in places where it’s just a particular assortment of people who get hired for a given night, and it’s one of these quintessential glorious moments that we all feel. You were describing your experience last night at your dance, where it’s just this incredible experience, and many of those are just, they’re not there. We’ve had them, but that’s not what you can capture in this. I had to have the recording criterion because otherwise it would be too big a project and I know my limits.

Mary Yeah, right, you have to have some creative constraints.

David Well, I’ve gotten some pushback, how come so-and-so is not on there? Well, you know.

Mary Container.

David Someone said so are you going to expand this to include all the bands? I said, you’re welcome to, go for it. I will cheerfully watch your website.

Mary Are you pretty much a sort of a self-taught documentarian? I mean, it’s such a vast array of skills that are required to put this all together. You’re talking about research, oral history, I have to assume some kind of database record management system, videography.

David For years, I felt that someone should make a movie about Ted Sanella. He was such an important figure and then Ted died. He wasn’t even 70 when he died. And it was one of those, oh, I guess someone could do it, but he’s dead, so it’s not going to include his voice. The line I’ve used is when you say, “I wish someone would do such and such,” the time to say that is when you’re standing in front of the mirror and you realize if something should be done and you feel something should be done, then by God, go and do it. And that’s when I looked around the universe and said, “Well, who should I make a movie about? Ted’s not here anymore. Who else?” That’s when I picked on McQuillen and did my first film about Mac.

Mary Paid to Eat Ice Cream.

David Paid to Eat Ice Cream. And Mac, it took 3 or 4 times before he agreed to be part of that. He didn’t want me to do it, it was drawing attention. And finally, after the third or fourth time, he said, you really want to do this, don’t you? I said, yeah, he says, all right, I’ll do it because you want to do it. That’s just the way Mac was. I’d done VHS stuff with my kids, and I’d made a movie once with video where I was editing because I had one deck with one thing and another deck , a VHS deck with another feeding into a third deck. And then of course, when you make a mistake, you have to go back and do it again. Then along came digital video. It’s like, whoa, it’s word processing for images and sounds just like, oh, this is cool. So I taught myself how to do that. I mean, I bought a good camera. I did a lot of research. I remember going around to all these people saying, well, how do you do this and how do you do that? A local friend who is a videographer, said David, just take the damn camera and shoot some footage and look at it. It’ll tell you exactly what you need to know. So I stopped worrying about manual settings for this and this, and I put it on automatic and lo and behold, the Sony engineers were a lot smarter than I was. So you learn, you make mistakes and you learn.

Mary You learn by doing.

David And you realize, you know, it’s not perfect. But imagine that you were an avid blues collector and you found a recording that no one knew existed that no one had ever heard of but it’s clear that it was Robert Johnson, and it was a 78 that no one knew about and you listen to the recording and yeah, there were scratches and cracks and pops and all these other things, but there it is.

Mary You have the recording.

David So whatever you do with any of these projects, you do the best you can and if it’s not perfect, you know, we have footage of people from years ago or recordings and it’s better to have that than not to have it. So my wish is that all the people who are shooting video now or doing recordings find a place for that to go. That they work with their local libraries, build up an archive. In New Hampshire, New England we’re really fortunate to have the New Hampshire Library of Traditional Music and Dance. In Vermont, you work for the Vermont Folklife and just to find ways of preserving our traditions. This project, the one we were talking about, a Hand for the Band, it doesn’t have Don Messer, it doesn’t have Jean Carignan. It doesn’t have Ralph Page, doesn’t have Schroeder’s Playboys or Andy Dejarlis, people who for years before were playing for dances. It’s really the people who are playing during the last 50 years or so of the revivals, and that’s sort of the period that I know and so that’s the part that I’m documenting.

Mary Like you said about calling, you have to find the things that make it fun for you.

David This is the part that I’m interested in and where I know something about it.

Mary Well, we are so lucky that you have this spark and that you looked in the mirror and said, okay, it’s me, because you just continued to create these delightful, vast records that I think they’re going to become more and more important as time goes on.

David Well, I hope other people enjoy them. I’ve certainly learned a lot.

Mary We definitely do. Well, I have three questions that I usually close with. The first, which you’ve already mentioned, is this tendency for callers to have a collector or a curator, mindset. And as I say this, I’m looking around the room that we’re sitting in and we’re just surrounded by dance books and binders and, so I think I’m not off the mark here when it comes to you. But I’m curious, I’ve been asking everyone that I interview how you keep your dances and a little bit about dance notation. So you’ve already mentioned, like, a yard’s worth of cards.

David Yeah, I can show you. I mean, I started out obviously doing my contra dances are all on cards, three by five cards. Initially I was typing on the cards, I still have a manual typewriter, it’s up in the attic now and then it was computer generated, but cut and paste onto three by five cards. My squares, my early squares, are on cards but most of that has now gotten moved onto an iPad. My English, English was a pain because you had The Playford Ball but then there were all these other dances, so I started putting them in binders and that was fine if I was just working locally but when you go off to a dance camp and you’re carrying this enormous weight of stuff. So for English, I use a program, The Dancing Master, that Ralph Canapa wrote. That’s the program that I use, where I import PDFs, and it’s basically a database and, you can categorize things, and so you search. “All right, I want a three couple dance that’s easy and it’s in either A minor or E minor” and boom, up it comes. It’s great because I can go off to a dance camp with my programs in mind but when I need to make a change, I’m carrying 1500 English dances with me. And increasingly I’ve started putting squares on that as well. I’ve got some contras on there, but for the most part, contras, they’re all on cards so I can carry a week’s worth of dance cards really, really easily so different formats for different styles.

Mary That makes sense and I assume you’re still collecting dances?

David Yeah, people are still writing dances. There are still wonderful dances. Every so often, less with contras, I remember being at a dance weekend in Louisville, and Gaye Fifer was calling and she called Trip to Wilson, Will Mentor’s dance. I was dancing, I was like, whoa, what’s this? And so I was sure to grab that dance. And I’m sure other callers did the same. You know, it was just different enough. And it’s also got a bit of an Englishy feel to it. I’m really interested in the cross-fertilization, of how—I’ve done whole workshops of how alien influences—contra dancing is like the English language, which is it steals or borrows from everything. So the piece that Allison Thompson and I wrote about the Dolphin Hey, starting in Scotland and working its way into English country dance and now there are contra dances with Dolphin Hey. Contra dancers and contra dance choreographers are really good at lifting from other traditions, doesn’t work as much the other way. David Smuckler has a dance called Bastille Day, which has circulate in it, which comes from modern Western square dancing into contra dancing and now into English country dance.

Mary Amazing. Do you have any pre or post dance gig rituals, things that you kind of do to warm up or wind down?

David Before, usually starting the day before, I try to drink a lot of water. I learned that from Tony Parkes. He said, you really need to keep your vocal chords hydrated. He says having a drink right before you go on isn’t the same. So that’s something I consciously think about is getting a lot of water in my system. I try to get a lot of extra sleep the night before a gig, but that often doesn’t happen. Yeah, like getting to the hall early, especially if I’m working with a band that I don’t know. I really want to get there and talk to them and meet them and schmooze a little, just get a sense of who they are. Who’s the person I need to communicate with? Who’s the band leader who’s sort of directing things? If I’m in a place I don’t know, I want to really meet my hosts, meet the organizers, make them feel appreciated. I think the organizers are the heroes of the dance movement. At the end of the evening or during, we clap for the callers and we clap for the band and we clap for the sound people, but it’s really the organizers and people who have never done that job do not appreciate how much work it is. People go to George Marshall’s Tropical Dance Vacation and just have a wonderful time. George is the master of being calm and smooth but it’s the classic case. You look at the duck just swimming serenely on the surface and underneath those flippers are busy paddling. A dance weekend that runs smoothly, runs smoothly because a lot of people have done a lot of work and are doing it even during the weekend. If they’re doing it well, you as a dancer aren’t even aware of it. So I want to get there and make sure that the organizers understand that I really appreciate them, I wouldn’t be there without them.

After a gig. I’m usually pretty wired. When I was traveling a lot in New England, as a caller, when you’re starting out, you have to do a lot of traveling, you do a lot of gigs for not much money. You know, the usual thing. “Oh, you don’t get paid much, but you get to drive hundreds of miles,” the standard line. Coming back from a gig a couple hours away, I’d have a CD going, for years it was the second Airdance album, the Flying On Home album. That was my go to, just high energy to keep me sort of pumped and then by the time I got home the adrenaline would be sort of out of my system. It’s hard at a dance weekend to sort of slow down because you usually have to be up early the next morning and I need to get to sleep. If it’s gone well, I’m really excited. I mean, the adrenaline is just flowing, you’re feeling it, you’re on stage, you’re seeing all these people out there having a great time. You’re right up close to the music and you’re having fun. You and I were talking earlier before we started recording, you teach the dance, you call it a few times, and you’re keeping an eye and periodically you’ll come in with the call if you see some people who need help. But mostly there’s not much to do when you’re calling.

Someone came up to me at the Flurry once and said, oh, this must be really hard. And I said, wait, I’m calling to 350, 400 people out there. These are hard core dancers, I teach it, I call it a couple times. I’ve got the Great Bear Trio up here or some amazing band. So I said, hard, hard is calling a wedding with an open bar that’s serving hard liquor, that’s hard work. I do a lot of gigs like that too. So calling for a regular old contra dance or a dance weekend, that’s not hard. The hard part is programing, that’s the hardest part. Once you’ve got your basic caller chops down, programing is the hardest part, figuring out what the right dance is for this group. So most post dance rituals is trying to get to sleep.

Mary Always.

David Introvert or extrovert? I’ve been following the series.

Mary You’re a listener!

David Yeah, I’m a reader. I don’t listen to it, I don’t do podcasts.

Mary Well, that’s why we do the transcripts.

David I’m so grateful that you do.

Mary And a shout out to our wonderful Ellen, Ben Williams’ mom who helps—speaking of thanking our volunteers—helps us correct the transcript.

David Because is it done automatically?

Mary We do a digital automated transcription, but then of course there are alot of errors.

David I’ve tried those sorts of things. There’s some fascinating AI errors. I’ve thought about that as I read it every month, hearing about it. When I go to a dance event I love schmoozing with people. I love talking to people. I’m not an extrovert in the sense that I don’t go to parties looking forward to hanging out with a lot of people. My solution to dealing with a party is to find a person and go off in a corner and have a conversation with the person. I spend a lot of time at home, sitting up at my computer working on all this stuff, and I’m very happy doing that. We live in a lovely house at the dead end of a dirt road, and so I’m very comfortable doing that. I like the balance that I have, where I can go out into the world and be social and then get away from it. So I don’t know where that puts me, you’d have to bring a psych major and give me the tests.

Mary Exactly. There’s no wrong answer.

David I know that.

Mary It’s just a curiosity, but, yeah.

David I feel so fortunate. I mean, I’ve been part of this world now, for this dance world for 50 years, 50 plus years. I’ve been a dancer. I’ve been an organizer, I call. I get to call in such different settings, and it’s just been such a rich part of my life, and I feel so fortunate to have had it there. So thank you everybody for keeping all this stuff going.

Mary And we are fortunate to have you in that world. Thank you so much for having me here in your cozy house at the end of the lane. And, thank you From the Mic listeners. We’re done!

Closing

Thanks so much to David for talking with me! You can check out the show notes for today’s episode at cdss.org/podcasts.

This project is supported by CDSS, The Country Dance and Song Society and is produced by Ben Williams and me, Mary Wesley.

Thanks to Great Meadow Music for the use of tunes from the album Old New England by Bob McQuillen, Jane Orzechowski & Deanna Stiles.

Visit cdss.org/podcasts for more info.

Happy dancing!

Ben Williams The views expressed in this podcast are of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect those of CDSS