I saw this guy yelling on stage and I saw 100 people doing the same thing at the same time because he said so and I said, ‘I want to be him.’

~ Tony Parkes

Photo by Doug Plummer

Tony has been calling square and contra dances for more than 50 years. The first Baby Boomer to take up the profession, he learned from many of the leading callers of the day. Dancers in 36 states, Canada, and Europe have enjoyed his clear calling, excellent timing, and positive, reassuring teaching. He has beginners doing real dances within seconds, but can keep experienced dancers entertained with a bit of challenge or elegance.

Tony has composed over 90 square and contra dance routines, some of which have become modern classics and he’s the author of two comprehensive texts on calling, one focused on contra dance and most recently, his brand new book: “Square Dance Calling: An Old Art for a New Century. He has also been featured on multiple recordings as caller, pianist, director, and/or producer. Tony and his wife Beth, also a caller, live in the Boston area. They divide their calling time between appearing at weekly and monthly dance series throughout (and beyond) New England and presiding at corporate, civic, and private events.

In their interview Mary and Tony chatted for over three hours! Tony is an encyclopedia of square and contra dance history, full of vivid recollections of the many mentors and sources of inspiration that have made him the caller, dance leader, and person that he is today. From his beginnings as a 14-year-old stepping up to the mic at Farm and Wilderness Camp to call Golden Slippers, to writing the foundational contra dance calling text which has helped so many callers find their way to the stage, to his most recent publication, in which, to use his words, he “gives away the farm” sharing his square dance repertoire and know-how…Tony Parkes is a gift to us all!

Show Notes

Soundbites featured in this episode (in order of appearance):

- All tracks of Tony’s calling were recorded at the 2011 Dare to Be Square Weekend in Brasstown, NC and distributed by CDSS as the DTBS Syllabus

- Tony calling Dosido & Face the Sides, track 033

- Tony calling the singing square The Auctioneer, track 133

- Tony calling The Kitchen Lancers, track 064

- Tony calling The Merry-Go-Round, track 157

Bonus Episode! Tony’s Audio Archive:

-

In addition to being an amazing dance caller, Tony Parkes is also a dance historian and collector of archival recordings of dance callers through time. In this short bonus episode of From the Mic join Mary and Tony as they listen to a selection of recordings together.

Other Links

- Tony and Beth Parke’s website has all manner of good things including access to their catalogue where you can order Tony’s books:

- Square Dance Calling: An Old Art for a New Century

- Contra Dance Calling: A Basic Text

- Shadrack’s Delight – 43 original dances by Tony! (The title dance, “Shadrack’s Delight,” celebrates its 50th anniversary this year!)

- And more!

- Tony Parkes interviewed by Julie Vallimont on our sister podcast, Contra Pulse!

- Check out this lovely video of Tony calling the classic square dance mixer “The Merry Go Round” at the 2020 Ralph Page Dance Legacy Weekend, including an introduction by David Millstone. The dance originated with Ralph Page, was adapted by Tony’s mentor Ted Sannella, and then adapted by Tony himself. Tony traditionally calls The Merry Go Round” as the last dance at the New England Folk Festival (NEFFA).

Dance Cards and Set Lists

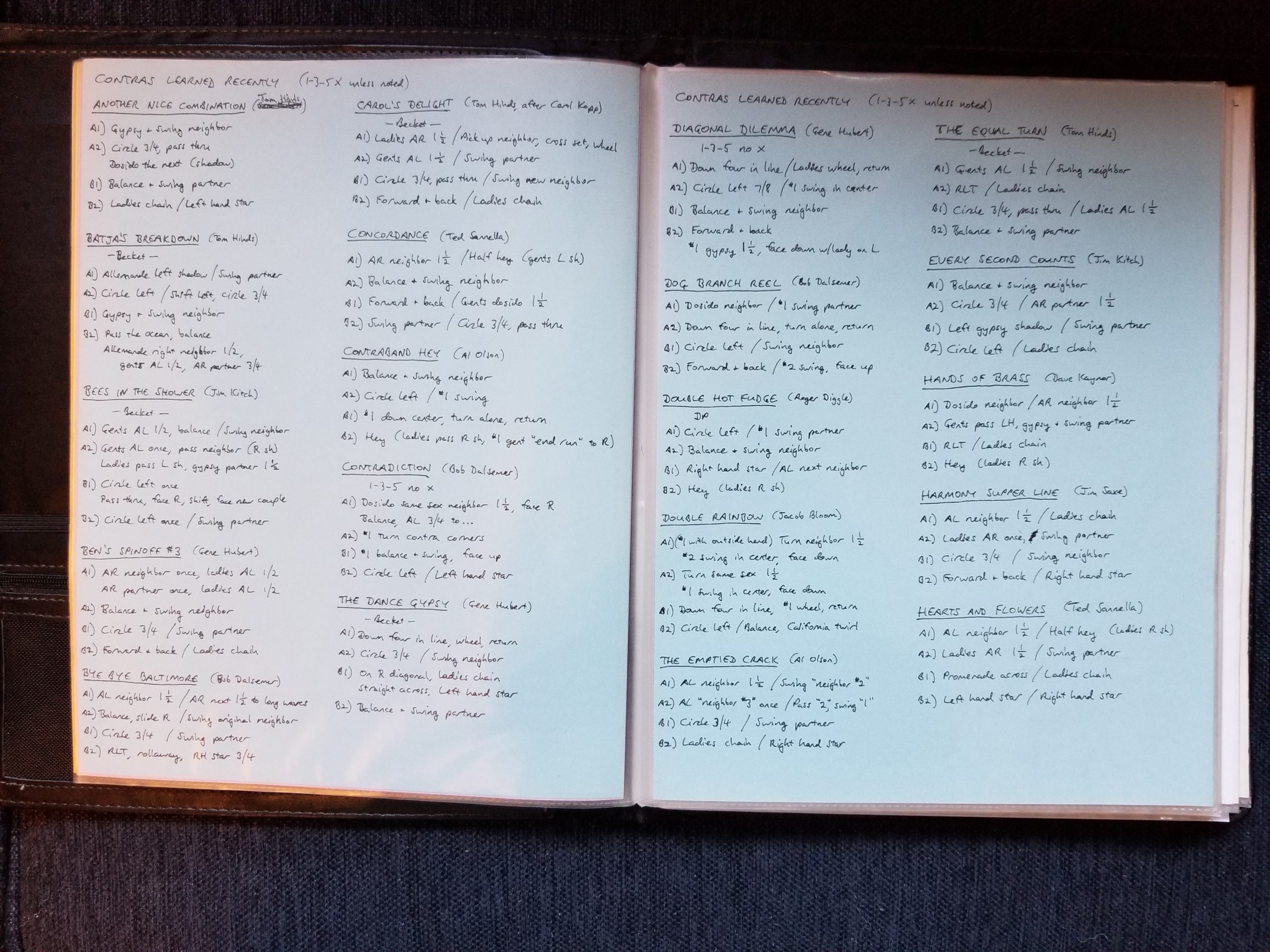

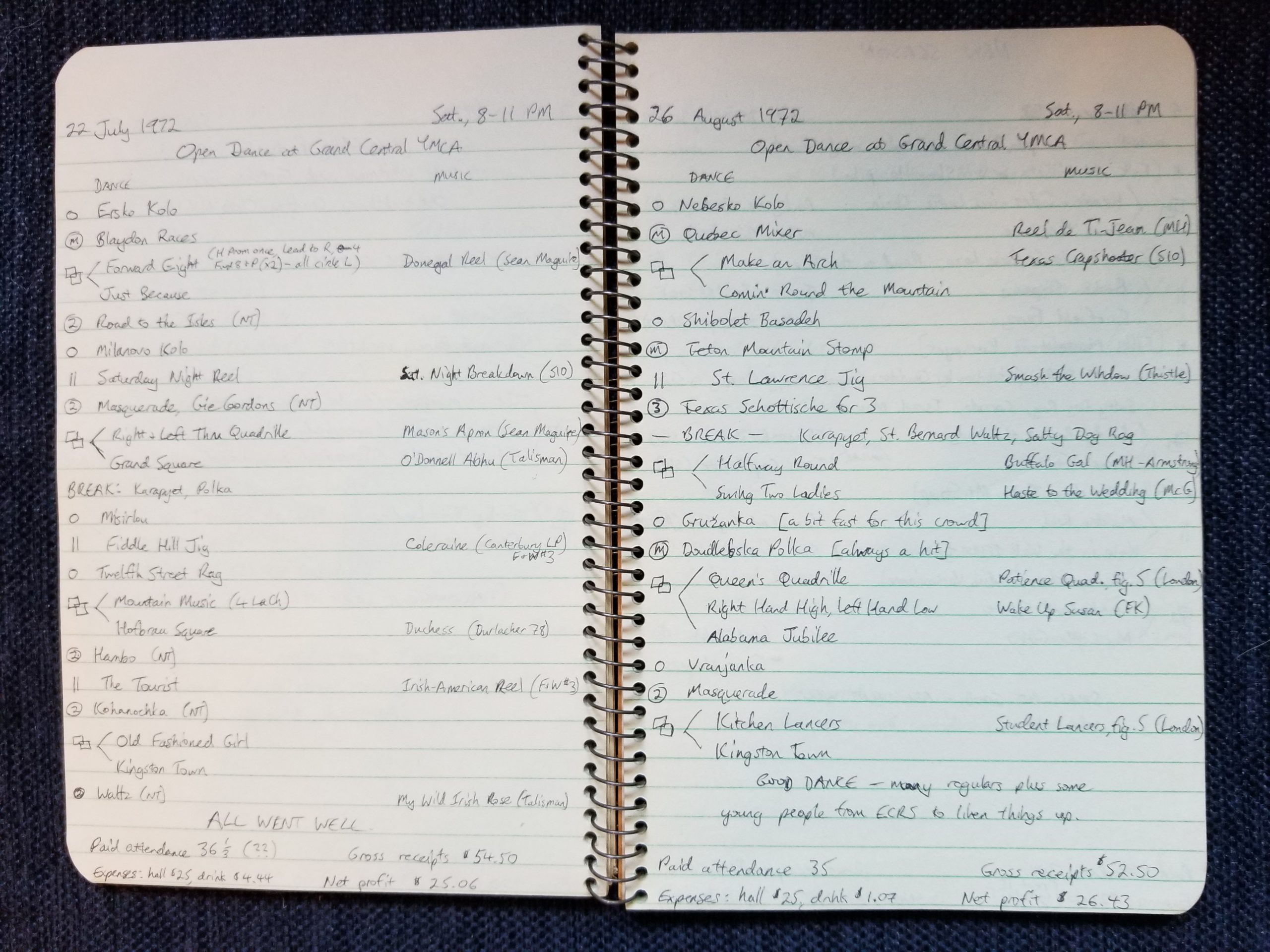

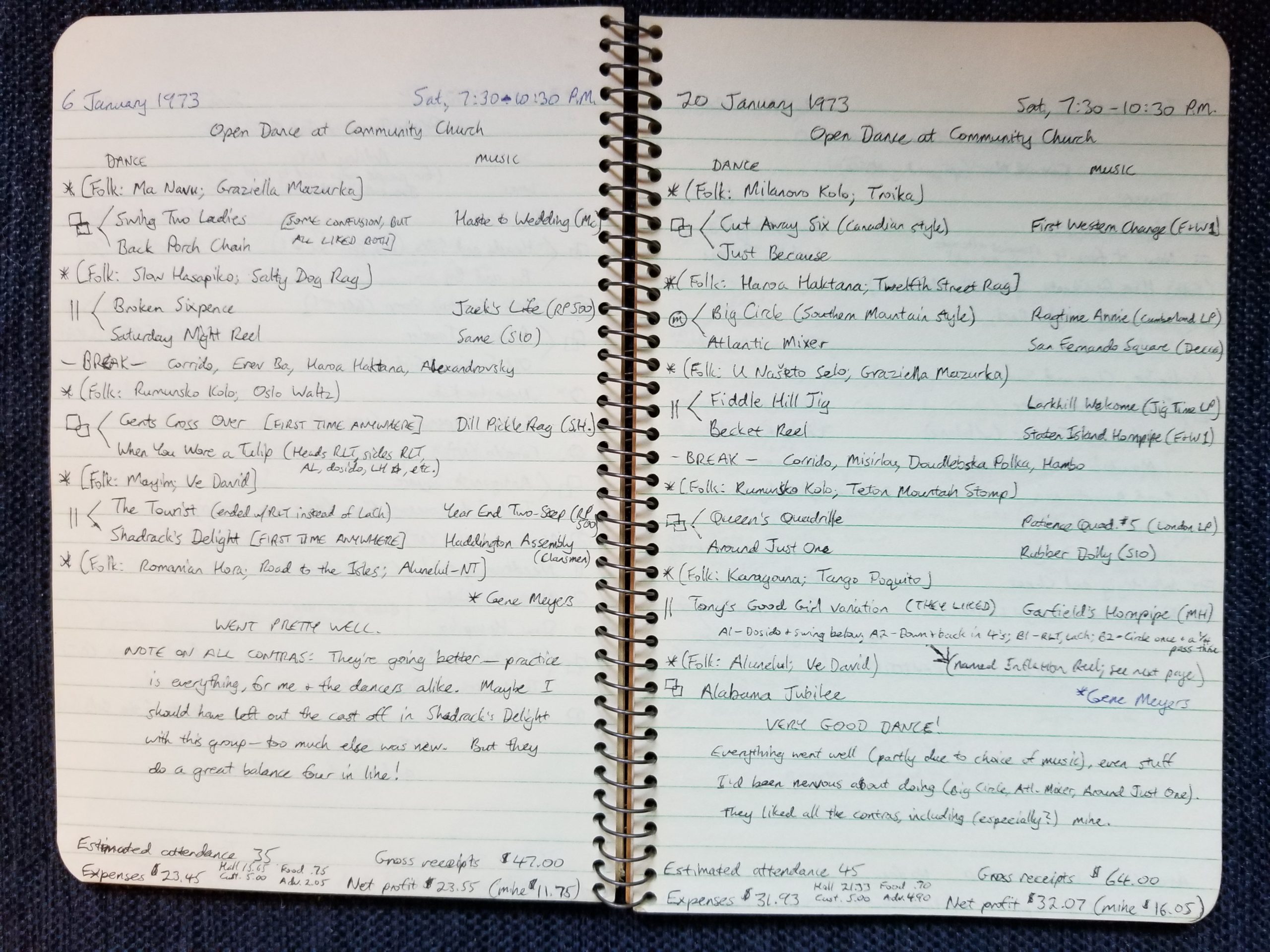

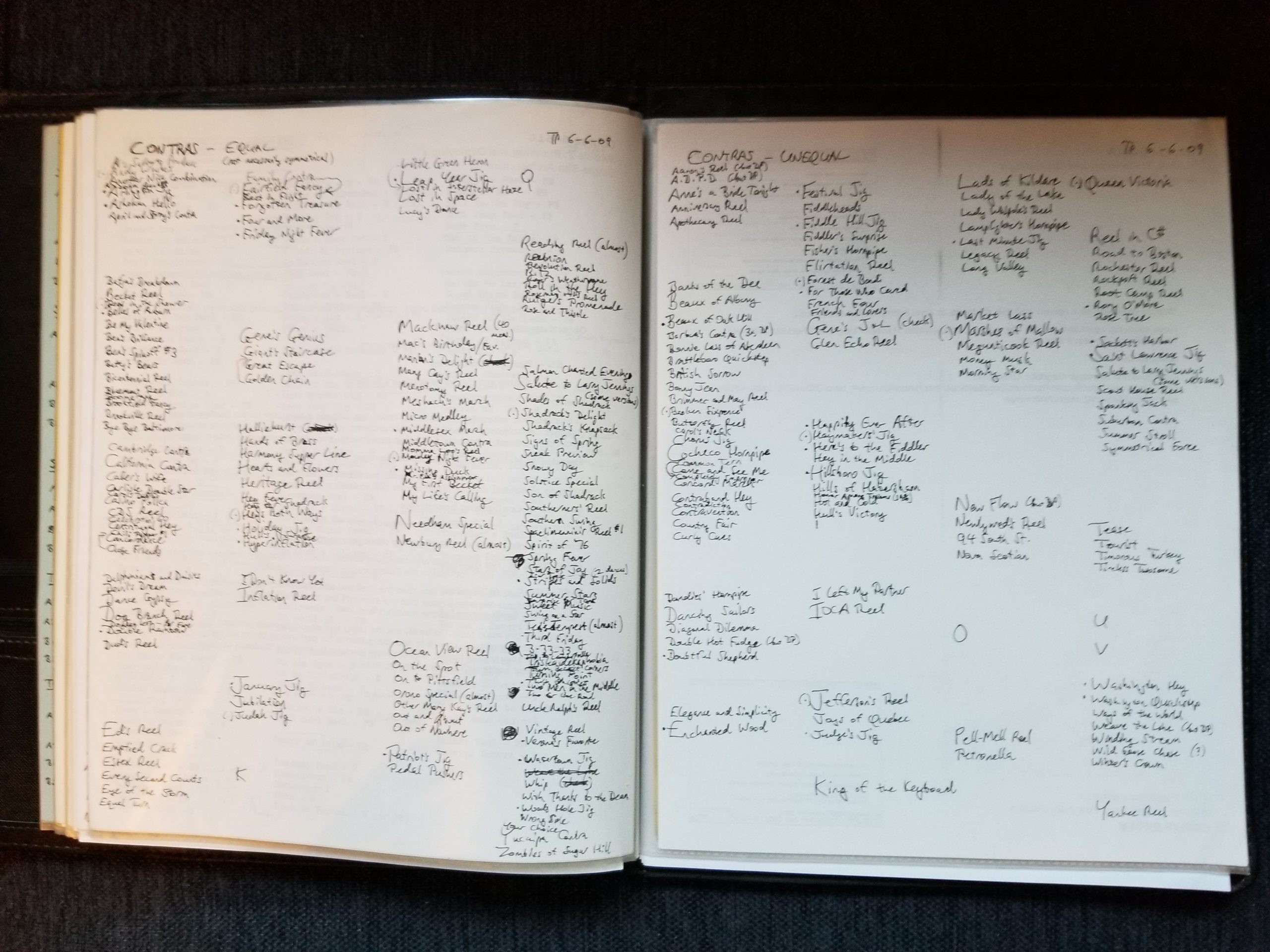

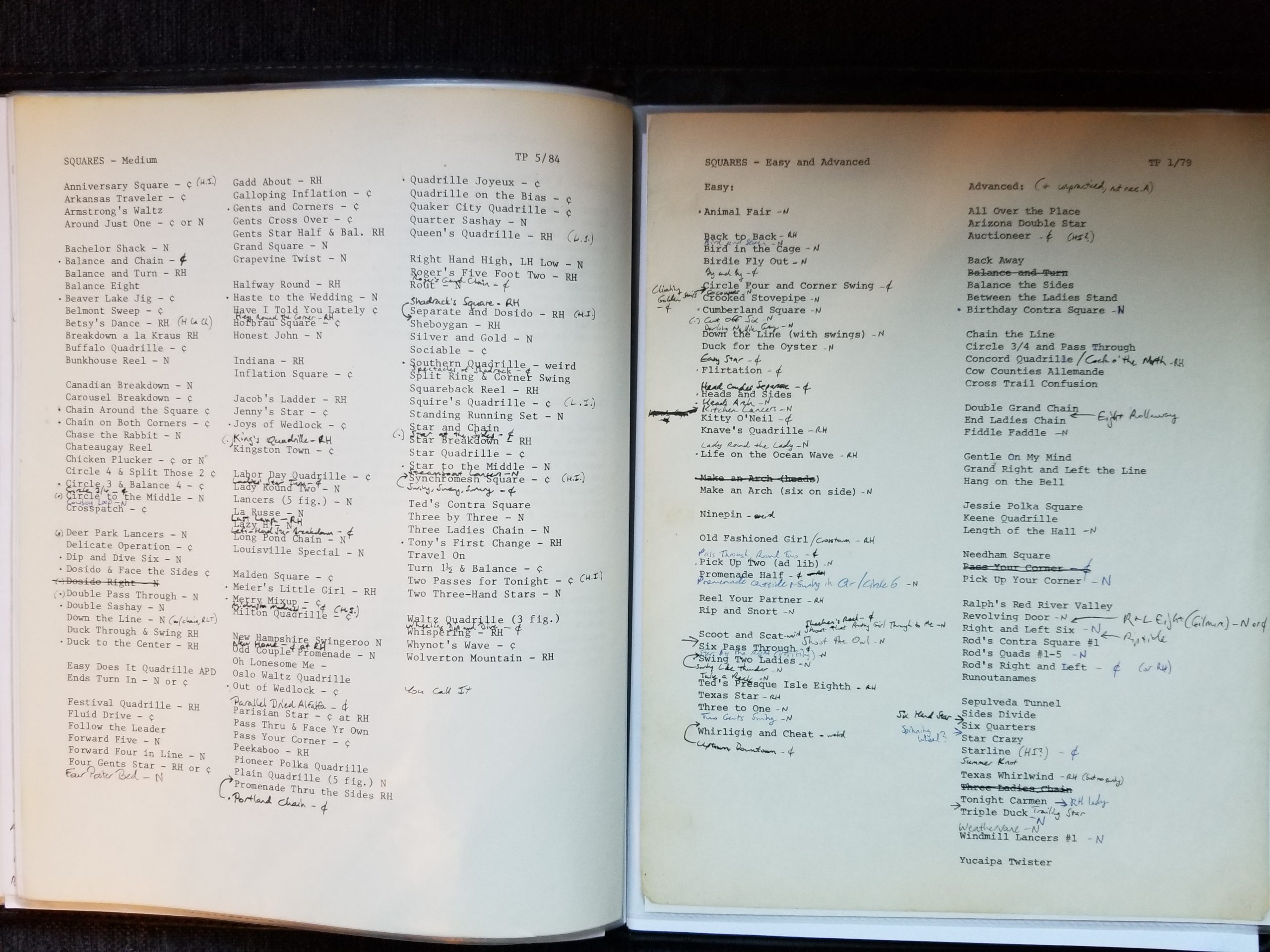

Tony shared photos of a his dance notation, which he keeps in an 8.5×11 folio (click to enlarge):

- Contras

- Dance Program – July 1972

- Dance Program, January 1973

- Last dance program pre-covid

- Title list, contras

- Title list, squares

Bonus Audio Clips

Click here to download a transcript of these audio clips.

Episode Transcript

Click here to download transcript.

From the Mic Episode 4 – Tony Parkes

Ben Williams: This podcast is produced by CDSS, the Country Dance and Song Society. CDSS provides programs and resources, like this podcast, that support people in building and sustaining vibrant communities through participatory dance, music, and song. Want to support this podcast and our other work? Visit cdss.org to donate or become a member today.

Mary Wesley: Hey there – I’m Mary Wesley and this is From the Mic – a podcast about North American social dance calling.

Through conversations with callers across the continent we’ll explore the world of square, contra, and community dance callers. Why do they do it? How did they learn? What is their role, on stage and off, in shaping our dance communities? What can they tell us about the corner of the dance world that they know, and love, the best?

Each episode we’ll talk to a different caller, but they all have something in common – a spark, a desire to lead, to share joy, to invite movement, to stand in that special place between the band and a room full of dancers (or people who don’t yet know that they’re dancers), and from the mic say “find a partner, let’s dance”

Tony Intro

[ Clip of Tony calling Dosido & Face the Sides, Dare to be Square Syllabus 033 ]

Today I’m happy to share some of my conversation with the great Tony Parkes.

Tony has been calling square and contra dances for more than 50 years. The first Baby Boomer to take up the profession, he learned from many of the leading callers of the day. Dancers in 36 states, Canada, and Europe have enjoyed his clear calling, excellent timing, and positive, reassuring teaching. He has beginners doing real dances within seconds, but can keep experienced dancers entertained with a bit of challenge or elegance.

Tony has composed over 90 square and contra dance routines, some of which have become modern classics and he’s the author of two comprehensive texts on calling, one focused on contra dance and most recently, his brand new book: Square Dance Calling: An Old Art for a New Century. He has also been featured on multiple recordings as caller, pianist, director, and/or producer.

I have to tell you my interview with Tony was epic. We chatted for over three hours! He is an encyclopedia of square and contra dance history, full of vivid recollections of the many mentors and sources of inspiration that have made him the caller, dance leader, and person that he is today. From his beginnings as a 14-year-old stepping up to the mic at Farm and Wilderness Camp to call Golden Slippers, to writing the foundational contra dance calling text which helped me and so many others find our way as callers, to his most recent publication, in which, to use his words, he “gives away the farm” sharing his square dance repertoire and know-how…Tony Parkes is a gift to us all. Are you ready? Here’s Tony.

Intro

Mary Wesley Tony, welcome to From the Mic.

Tony Parkes Thank you, Mary. It’s great to be here.

Mary Wesley So glad to see you and spend some time talking about calling with you. I should say for our listeners that you have done a wonderful interview with kind of our sister podcast. From the Mic is supported by the Country Dance and Song Society, and it was inspired by Julie Vallimont’s podcast Contra Pulse, which focuses on interviewing musicians who play for contra dancing. And so, of course, that is one part of your resumé, a wonderful career as a dance musician, but I kind of think of you as equal parts musician and caller. I’ll be curious to see if that’s an accurate description. But it only felt natural to bring you on From the Mic as well to maybe go a little more in-depth on your experience as a caller. So I’ll just say for our listeners that Tony and I may cover some of the same things that Julie talked about on her interview, but we will cover new things as well. So I’ll reference a little bit of Julie’s interview and we can kind of think of these as being part of a set, Tony Parkes on Contra Pulse and Tony Parkes on From the Mic.

So, you know, I do always like to sort of start at the beginning and hear a little bit about where and how people came into the world of country dancing or social dancing. And I have listened to your interview with Julie. When you were describing that part of your story, you mentioned feeling like you were at the right place, at the right time, in certain ways. So you kind of caught the tail end of the square dance boom. You got to experience the contra dance revival. One thing that jumped out at me was, I think you said your first contra dance was with Ralph Page at the mic and that your second one was with Dudley Laufman and Ted Sannella, you mentioned as one of your mentors. So now you have, you know, just even those few little points tells me that you crossed paths with some really significant people in the world of country dance, of contra dancing, square dancing, particularly in New England. And yet you caught it at a time when someone who is new and young and interested in seeing these traditions continue was a boon to some of those great leaders and callers and that they were excited to pass things on to you. So I’d love to hear a little bit more from your perspective about those connections, and also invite you to share even though you were there, you had some great serendipitous timing and encounters. Something pulled you onto that path and kept you moving forward and learning more about how you could be part of that world. So how, from your perspective, did that unfold?

Tony Origins

Tony Parkes Well, that’s the $64 question. You know, it’s hard to put into words without getting into theology, but I really do feel like I was remarkably blessed by being in the right place at the right time. I don’t think I ever thought of it in quite this way before until you spoke just now that it was mutual that the callers were excited to see somebody young and, you know, under 45. And of course, you know, I was a teenager at the beginning of this segment of my life. They were excited to find a young person who was interested enough to want to take up the mantle. I was excited at being able to rub elbows with the greats in this field. I’m not sure I could tell you who was more excited. Everything felt like it was coming together. You know, the timing in terms of the dance revivals and also the timing in terms of who I was able to meet. Some of the people I met were retired or semi-retired. Even Ralph Page had retired from calling every week, but he did an occasional workshop and that’s how I met him. And I couldn’t swear to it now whether it was Ralph or Dudley that I danced to first. I do think it was Ralph. And this was when I was still living in New York, where I grew up, and I was doing international folk dancing with Michael and Mary Wesley Ann Herman at their Folk Dance House. And it was mostly eclectic international, but occasionally they would have an American day. And at this point in the mid-1960s, they would have a Ralph Page Day every year and Ralph would come down from New Hampshire. He would do an afternoon workshop and then people would find their own dinner, and then he would come back for an evening dance. I had heard of him and I had done some reading. And of course, I’d heard the Hermans talk about him, and he was the grand old man of squares and contras. I had done a lot of square dancing in grade school and at summer camp, a couple of different summer camps, notably the Farm and Wilderness Camps in Vermont. I remember at one point trying to get people interested in contras at Farm and Wilderness because it was all squares. And what I was doing in New York was mostly squares, but I had been exposed to a little bit of contra dancing at Folk Dance House and particularly on Ralph Page Day. And I remember I couldn’t get anybody interested in in contras at that stage at Farm and Wilderness Camps. And in the summer of ’65, I was at Tamarack Farm, which is their teenage coed work camp. We had folk dancing to records every Wednesday night and we had a live music square dance every Saturday night. Dudley came about midsummer and called a dance, an evening for the teenagers, and he invited some of us to his place in Canterbury a couple of weeks later and so I went to his house party. The thing I remember most about that was that there was a very large hearth, stone hearth in front of the fireplace that was a few inches lower than the wood floor. The hearth was big enough that if you danced in that room, you had to dance sometimes on the hearth and sometimes on the wood and it was a real split level floor. But anyway, a few years after that, as I understand it, after I left, Farm & Wilderness went pretty much all contra as a lot of places around the country did. People don’t always understand what I mean when I say that in those days when I got started, it was all square dancing. They have a mental picture of people in petticoats and string ties and dancing to records and taking lessons and that’s not all what it was. It was, you know, even in New England, even the people who were diehard traditionalists, what they were doing was probably more than half squares and in some towns it was all squares. But even where it was half contras, they called it square dancing right up until the early 1970s I guess. The whole activity, the whole hobby was called square dancing and that didn’t mean club square dancing, that just meant whatever it was you were doing. When I started going to the NEFFA festival in 1969 the American dancers, some of them did wear matching outfits and string ties and a lot of them didn’t. There was actually not as much of a divide in those days between what they called the eastern and western style squares. That was just beginning to be a thing that so-called Western dancers liked to do slightly more complicated figures, and they had a couple of calls that the New England style callers didn’t use, but there was some interchange. In fact, in those days, it was possible for somebody who had a lot of experience doing traditional squares, it was possible for somebody like me to just walk into a square dance club without going through the lessons and dance with them. I did that in two different places when I was still in New York City and starting in, I would say sometime in the 1970s that became impossible. There were just too many calls in the other style for people to just jump right in.

Mary Wesley And that was the time when there was this shift towards contra as well? Was that related?

Tony Parkes Yeah, that’s a good question, I’m not sure I’ve thought about whether that was related. It’s possible. The first inkling I had that there was going to be a shift on the traditional side was when kids started calling it contra dancing. They would go to a Dudley dance and they would do squares there as well as contras but they started calling it contra dancing and I’m guessing that they wanted to separate it in their mind and in people’s consciousness from square dancing because they probably knew one or both of two different kinds of square dancing: the kind they had in grade school where they were made to do it and they hated it because it probably wasn’t presented very well. And then there was the formal, organized, codified dancing in clubs with the lessons and the outfits and the recorded music. The kids wanted to make it clear that this was not either of those so they focused on the contras. And of course, contras have a lot going for them, they’re inclusive. You can just step in at the end, you don’t have to wait for exact numbers. And the way Dudley ran his dances, it was pretty freewheeling, although he didn’t believe in total chaos. But the kids could do their own thing up to a point, they could put in fancy steps, they could hop up and down, which was discouraged in the square dance clubs. So, yeah, late ’60s, early ’70s people started calling it contra dancing rather than square dancing. At the same time, a lot of groups started focusing more on the contras, doing more contras and fewer squares in an evening. One of the things that I regret about the way things have changed is the lack of variety and the tendency to specialize. Because when I got started both in New York and in Boston a typical evening would have a lot of variety. It would have, several of the series were about half squares and contras and half international folk dance. Ted Sannella, just about always in his series dances, would put in a lot of international dances, and sometimes if the dance had a live band, he would do a couple of folk dances in a row to records. And that was a time that the band could go and take a little break. In New York where I grew up and where I first started dancing, one of my mentors was Dick Kraus who called at Columbia University every Friday night and that was three folk dances and then a set of three squares and then three more folk dances and so on through the evening. So it was what I grew up being used to. Some of the dance camps that I went to, again, the program was varied and whether it was international folk or just more couple dances than you see now at a contra dance. And of course, there were squares and contras at most of these events. And so, you know, my regrets are number one, that so many evenings are 12 contras and a waltz. My regrets are, one, that there are few or no squares and two that there aren’t more non-group dances, either couple dances or no-partner dances, the sort of things that I grew up with.

Mary Wesley I definitely want to get more into those ebbs and flows of style and preferences that you’ve seen over the years. But maybe just to spend a little more time in your kind of formative years, do you remember kind of how you first came up to the caller’s mic? Or is there a significant like first dance first time calling that you can tell us about?

Tony Parkes Yeah, it was at Farm & Wilderness Camps and when I was there, I don’t know what it’s like now, but when I was there, square dancing was a big thing. It wasn’t quite to the point where – you may have heard of the F&W String Band, which was campers and counselors. They made a few LPs, and they also put out Dudley’s first LP. So eventually playing in the square dance band became one of the camper activities. But that wasn’t so when I first started going there. And let’s see, it was always a live band, but it was made up of counselors, 18 and up. There was no hard and fast rule, but that’s just kind of the way it worked out. I had square dancing in school, and the teacher would call from the piano and also play a few records with calls and it was good. I liked it, but I didn’t really get hooked until I went to camp and we had basically a Dixieland band up on stage, six to 10 pieces just wailing away at the singing calls. And a caller who you could hear a mile away. I could hear it when it wasn’t my age group dancing I would be lying in my bunk on my way to sleep, and I would hear the dance up on the top of the hill at the dining hall. And I could usually tell you what he was calling even that far away. So that was really exciting. And that was where I got hooked for life on the whole phenomenon of called dances. I like to tell people that I saw this guy yelling on stage and I saw 100 people doing the same thing at the same time because he said so and I said, I want to be him. I’m not sure I could have put it into words back then, but that was certainly a feeling. So I danced for several summers there, and when I was 14, the caller took me aside in the middle of the week and said tomorrow night at the Big Lodge dance, which was the name for the intermediates, the 11 and 12 year olds, which was like one level lower than I was at the time, he said tomorrow night at the Big Lodge dance, you’re going to call Golden Slippers and I said, I am? Because he had been watching me and not just that summer, but summers before. He saw that I was mesmerized by the whole thing and knew I would be looking up at him and I would be calling along with him under my breath. I think it’s quite possible that he had his eye on me for a couple of years and he was just waiting until my voice settled down. Because of course, when a guy is in his early teens he’s a soprano one second and a bass the next. Even when I started, when I called that first dance, my voice cracked three times. I counted them, but I got through it. I didn’t make any mistakes. I didn’t give the wrong call at the wrong time. So I think it was the following week that he had me call my first patter call, which was forward six and back and the left hand lady under. I forget what tune they used, but that was it. I came back the following year and I did a little bit of calling and then I came back as a counselor. Later on, when I was 18 and I was the assistant caller, they gave me $50 extra for the summer. I got $200 for being a junior counselor and 50 extra for being the assistant caller.

Mary Wesley Big money for calling.

Tony Parkes Yeah. Well, and of course, multiply those numbers by 10 now, because I think the camp costs about 10 times what it did back then, and hopefully they pay counselors close to that 10 times what they paid back then.

Mary Wesley And what a great opportunity to be picked from the bunch like that, to have someone notice your spark.

Caller and Musician

Mary Wesley So I introduced you as sort of equal parts caller and musician. I’m a caller myself, so of course, I kind of feel a little more in tune or aware of your calling. But is that right or how do you see yourself and how did your musician and caller roles kind of evolve?

Tony Parkes Well, I love them equally, but I’ve done a lot less playing than calling over the years. I did more in my first few years in the dance scene. One big reason for that is that almost immediately, within a few years of when I started, it got so there were a lot of good dance musicians including good piano players, good rhythm people and I felt like there was more of a need for very good callers then than for good musicians. That we weren’t getting the young callers as fast as we were getting the young musicians. And a really crass reason is that typically, especially in those days, the caller got more money than any of the musicians. That depends partly on who’s organizing the dance, who’s bringing sound and all that. In those days, it was likely to be the caller. And that’s still true for private parties where often Beth or I will get the call to do one and so we will find the musicians and we will take the sound and do the sound and so we do take a little more than we give the musicians. But if it’s a dance camp or if it’s some other kind of event, a festival where I don’t have to do any organizing or do anything with sound, I just come, call, leave. I think it’s appropriate that the caller get the same as the musicians. So, you know, it’s partly for selfish reasons, but also because I felt like I was needed more behind the caller’s mic than I was at the piano. So I would say, you know, 80/20 in favor of calling just the way things worked out. Although I should also say that I think callers who have musical training are at almost an unfair advantage, especially in New England style, square as well as contras because the dance is so traditionally wedded to the music. So the more you know about music and the more you can feel it on a sub-verbal level, the better your calling is going to be.

Mary Wesley Absolutely. I think that’s such a unique perspective that caller/musicians can offer, and my ears have been perking up as you’ve described several people calling from the piano, which I feel like I don’t see these days. Was that a more common thing? And did you ever do that as a piano player?

Tony Parkes I have done it. I prefer not to, because one or the other or both tend to suffer. It’s hard to focus completely on both at once. It’s more traditional in some areas than others. In upstate New York it’s almost de rigueur. It’s a long standing tradition that the caller plays an instrument. It’s not usually the piano, it’s sometimes the fiddle. It’s sometimes the guitar and I think most often it’s the accordion in New York. And that may be partly the influence of Floyd Woodhull, who was the most influential. He was the Ralph Page of New York state. He had a band and it was in great demand, both for community dances, for regular public dances and for private events starting in the 1920s or ’30s, I think, and going right through to about the ’60s. He always played the accordion and called at the same time. So it may have been his influence, or it may just have been that the accordion is a good instrument for square dancing because it’s rhythm and melody and you can watch the dancers while you’re playing it so you can call. Because, for instance, when I was playing piano at Farm & Wilderness, which is where I started playing for dances, the piano was set on the stage so that the pianist had their back to the dancers, it was against the back wall next to the fireplace. Oh yeah, I was playing for dances before I was calling. That was the other thing the summer I was 12. I played for all the dances, except the ones that I wasn’t old enough to stay up for. So it went one whole summer. Then I was the first camper, the first under 18 that they had in the band on a regular basis. And of course that tipped off the caller that I was that interested in the dance and the music. The following summer I didn’t play piano. I was getting interested in girls and then trying my luck on the dance floor finding a congenial partner. But then the following year was when I started calling. But yeah, I have called as a novelty, from the piano. I did it early in my NEFFA experience. It was like ’71 or ’72 I think when I called in the main hall from the piano and for at least one of the numbers, there wasn’t anybody else playing. I forget why. Just that the whole orchestra, I think, wasn’t there, but I wouldn’t want to do it as a regular thing.

Mentors

Mary Wesley Yeah. Multitasking, as you say, I think usually something suffers. We like to think we can do it all, but it’s nice to have a team.

[ Clip of Tony calling The Auctioneer, Dare to be Square Syllabus 133 ]

You’ve mentioned a few mentors significant to you in your development as a caller. Can you talk a little bit more about some of the folks that were significant to you and what they offered or what you still hold from some of those mentors?

Tony Parkes Sure. I think the overall the most significant thing they offered was encouragement. Telling me they believed in me and they thought I had what it took to go farther because I’ve lived with depression off and on all my life, and I did not have a real good sense of self, especially as a teenager. So it meant a lot to me to have people tell me I was good at something. And not only that, but good at something that made a difference in the world. You know, good at something constructive that it would do a lot of people good. And that’s, I think, primarily what I got from Ralph Page. I don’t think I learned a whole lot about the mechanics of calling from listening to him. What I got, I got mostly from other callers, but what I got from Ralph was that he believed in me because he was my grandparents’ age, and it must have hurt him to see so few younger people stepping up and wanting to be part of this. There wasn’t a whole lot he could do for me, I think, except encourage me, but he certainly did that. As I said, I went to Ralph Page Day when I was living in New York, and then I started going to his camps that he would run at East Hill Farm, which was sort of the New England equivalent of a dude ranch. It’s a farm-based resort in New Hampshire, and he would have two or three camps a year at East Hill. That’s, I think, where I met George Fogg actually for the first time, and he really made the English dance exciting for me. I also met Roger Whynot, originally from Nova Scotia, and he moved to Massachusetts, and he was one of my mentors and one of my encouragers when I moved to Boston, along with Ted Sannella and Louise Winston. Ralph was always, as long as he lived, he was always there, saying “Attaboy” in one way or another. I remember when I was trying to put a live square dance band together in New York, I wrote to Ralph and told him what I was doing and invited him to use us next time he came down to New York and he wrote back and said that was really kind of me but he had a rule not to work with bands he didn’t know and I’m sure that he learned that the hard way as many callers do. He also said try to find a bass instead of a drum because at that point I think I hadn’t. He said with the drum, all you get is noise, with a bass you get harmony too. And he closed the letter saying, I like you, Tony, and I believe in you otherwise I wouldn’t bother to write this stuff. So that was Ralph, the grand old man. I have some, some audio clips of him that I’m hoping to play during this interview. And then, of course, Dick Kraus at Columbia. I mean, you know, just imagine having a young teenager come up to you and say that he’d called a couple of dances and having the guts to ask him to call at your big 100 or 150 person dance. He must have seen something in me because he kept inviting me back. And then, as I said, Louise Winston and Roger Whynot, even before I moved to Boston because I remember taping them at their dances. The two of them and Ted Sannella were the big three among the callers that were active then, the big three who encouraged me. I remember one Ted inviting me to come along with him to a private party where nobody knew how to dance, so I could see how he dealt with a crowd like that and that’s really unusual, I think, for an established caller. You know, he didn’t let me call at that private party but he let me in and watch and usually private means private.

Mary Wesley: What do you think he was trying to get at there? Why did he see that as an important experience for you?

Tony Parkes Well, I think because he believed as I believe now that private parties, so-called one night stands, church dances, school dances, country clubs, whatever are just as important as series dances and that it’s important for an all round caller to be able to deal with a totally new crowd and turn them on to dancing, or at least not turn them off. You know, some people will think, oh, you know, beginning group, we can get a beginning caller. And I think it’s an inverse law that the less seasoned the dancers are, the more seasoned the caller needs to be. I certainly wouldn’t, although I admit that it’ s hard, it can be hard for a new caller to get exposure, to get practice time because established dancers aren’t always going to have the patience to hold still for a new caller. So some new callers end up having to call to non-dancers because they can’t get the dancers to hold still. But in general, I think we need to reserve our very best calling talent for the non-dancers. Through the years, half or more of my gigs have been non-dancer events and I love them. Some callers dislike them enough. I think that they don’t do them, but I love them. I think I may have heard it from Dudley, but…”I love beginners. They have nothing to unlearn.” You know, no bad habits. Of course, Dudley says, don’t call them beginners because they’re not necessarily beginning anything. You can’t afford to think of them as prospects for your club or your series. You have to give them something that’s complete in itself and then hope that some of them go on and you can tell them about the other stuff, but don’t sell them on it. Don’t say you’re not really dancing until you’ve joined one of these groups.

Mary Wesley That’s a great perspective. How did you see Ted and deal with a one night stand or what was he like in that setting?

Tony Parkes Well, very, very much like how people remember him in general, which was keeping the light touch, putting humor in, but not making fun of people, never losing his temper, demonstrating the best way to do something without saying, you know, this is the only way, keeping the ball moving. I think of it as just basically a good calling practice, the “best practices,” as we would say nowadays. I’ve made a point of, over the years, looking for non-dancer events, the square dances, barn dances, whatever and going to them whenever I was able, because I like seeing how other callers handle non-dance crowds. and I can almost always learn something, even if it’s something about what not to do. But more often I’ll get, you know, a punch line or a teaching technique, a way to say something that’s more concise than what I was using. My teach of the grand square is a blend of what I learned from listening to three different callers. And again, you know, if you steal from one source, it’s plagiarism. If you steal from three or more, it’s research. So I researched my grand square teach.

Mary Wesley That’s great. We can go so deep on any of these but did we cover all your mentors? Was there anyone?

Tony Parkes Oh, far from it.

Mary Wesley I know there’s so many.

Tony Parkes Actually, when I think of mentors, I put them in two categories, the ones who I danced to live, who encouraged me in person. And then there were several that I think of as almost mentors because I never met them. But I played their recordings over and over and learned a lot about mechanics and style from them.

The love of calling

Mary Wesley So you’ve mentioned a lot of really significant mentors. I’ve heard you say a couple of times, they saw something in you. There was something that…they clearly felt you were worth their time. You were worth some of their energy. And this is getting into perhaps the abstract or philosophical but what do you think it is? What do you think they saw? I have an idea that it might be love, or something that shows in you that this is something that’s really important to you. But is it something you can put into words at all?

Tony Parkes I can try. I think that is a large part of it, that they saw that I really loved this on a gut level. You know, as I said, I felt inferior as a kid and into my teens and felt like I wasn’t really good at a lot of things. And the things I was good at were not things that were valued. So I reacted really strongly. I responded in a positive way, really strongly to this idea that not only had I found something I loved, but that that my elders felt it was worthwhile, that they believed in it, too. It was almost like a religious conversion. They saw also that I was capable of taking something seriously and working at it. And it was, you know, it was a virtuous cycle, the more I looked like I knew what I was doing and cared about it and I took it seriously, the more encouragement I got and the more encouragement I got, the easier it was to take it seriously. And working at it didn’t feel like work because I was enjoying it so much.

Mary Wesley How has that carried forward as you have grown as a caller? You mentioned earlier you’ve recently published a book on square dance calling. You also published Contra Dance Calling. I don’t have the square dance one yet, but there it is, so that strikes me as a big, big part of who you are too is as someone who wants to bring people in and enable folks.

Tony Parkes And pay it forward. They say when you’re mentoring, the mentee has to show up of their own accord, you can’t force it on somebody. And I have not been blessed with one-on-one mentorship relationships by and large. But I do have a background in writing and publishing, and this is another way I feel like there’s somebody up there directing my life because right from when I first went to Farm & Wilderness Camps at age 10, I got involved with the weekly newspaper, the mimeographed sheet that the campers put together with a little help from a counselor. And over the years, I’ve done a little writing on various things, and also my day job has, ever since the mid-’70s, my day job has been proofreading and copy editing, first for scholarly books and more recently in the financial services field, where I do marketing material because that’s where the money is. I love doing books, but they don’t pay that well. It feels like my whole life has been a preparation for being a master caller in the sense of one who trains other callers and in doing things with the written and printed word, and in the books I’ve been able to bring those two threads together.

Mary Wesley Yeah, that’s important work. I think that I got my copy of your contra dance calling text at the Ralph Page Dance Legacy Weekend over at the UNH library. It was a significant moment and it was so exciting to be able to have a whole book to look through that helped me explore this thing that I was just getting started with, too. So yeah, it’s definitely a significant gift to us all.

Tony Parkes It’s always heartening to hear that it’s been helpful to some people because I know not everybody learns well from a whole lot of prose. There’s a tendency now to want to break up the printed page, and school textbooks now have all kinds of color and sidebars and bullet lists. I tend to write prose start to finish and it’s always good to hear that it’s helpful in spite of being drier than some presentations. You know, some people learn from hearing and some people learn from seeing it in print. Whatever I can do, I will. I still want to do a series of called recordings to supplement the squares book because I feel like one of the big problems of squares is that people don’t have role models the way I did. The recordings are harder to find, and there aren’t as many master callers out there doing squares, doing them well. So a very important part of my squares book, I think, is the 30 pages or so in the back in the resources section where I point people to other books and recordings and websites and videos and so forth because I don’t want them to learn just from me. I want them to learn from a lot of the greats the way I did.

The Role of the Caller

Mary Wesley OK, where do we want to go from here? I really like hearing from people how they think about the role of a caller, kind of what’s the caller’s job description and I actually, just because I have it right here, I’m going to hold up the cover of your contra dance calling text book because the art is so great to me because it’s from the caller’s perspective. It’s the mic up on stage with a hall full of expectant looking, I would call them expectant looking dancers, and as a caller I feel things when I’m looking at that. Was that a deliberate choice?

Tony Parkes Well, I wanted to do something from the caller’s point of view, and it’s a cover idea that hasn’t been used, at least on any prominent dance books that I can think of. We’ve gotten a lot of compliments on that design, but we’ve also had one or two people say that it’s really intimidating to look at, and I tell them that we had to tone it down. The artist’s original design had one of the guys near the front looking up and crossing his arms like that. And so we said can you do something? I’ve got it here. Yes, some of the people farther back are more like arms crossed, but the ones in the front have their arms down.

Mary Wesley Right, they’re a little less confrontational .

Tony Parkes Some people have said, oh, I know who that is, that’s so-and-so. And the artist says that – she went to the Scout House several times and took photos and made sketches. She says that the dozen or so people in the front are composites, but some of the people in the back are real. And you can…Ernie Spence, who was a well-loved dancer of, I guess, my parents’ generation in the Boston area is back there with his bald head.

Mary Wesley Oh, how fun. Well, it’s such a communal activity. It’s very understandable to want to build in some real-life connections.

Tony Parkes So what were you saying about the caller’s role?

Mary Wesley Yeah. Well, I referenced that the cover artwork there, because I think it really conveys, a sense of at least the caller’s position. You’re in front of a room full of people and they want something from you and you have a microphone. You’re the loudest voice in the room. If the sound system is working properly, hopefully they can all hear you. But what do you think of as the caller’s kind of job description?

Tony Parkes Well, I’ve always said that the caller is a curious combination of a teacher and an entertainer, and it depends also on the kind of event. At a one-nighter, a non-dancer event, you’re more of an entertainer than you are a teacher. You are the entertainment for that night. I think in both of my books, I’ve said, last month it was a scavenger hunt, next month it’s a Vegas night if you’re calling it at an Elks or somewhere. And so this month, it’s you. You are the entertainment. Your job is not, as Dudley says, don’t call them beginners. Your job is not to teach people to square dance or to contra dance. Your job is to make people feel good. Give them a good time. And I would add, bring them together, and facilitate connections. Either new connections that they may not have had before, or reinforcing connections that they already have. I think church or synagogue does some of the same thing. I mean no matter what your belief system is, one really important aspect of a faith community is the community, that you’re bringing people together over shared values. And so even at series dances where I have other dynamics to deal with, I try to approach each gig in that spirit, in the spirit of my number one job, even if people don’t realize it is to bring people together.

Mary Wesley What are the things that you do or the choices that you make as a caller that you feel contribute to that goal?

Tony Parkes Well, at a series dance, I tend to avoid dances that are too tricky. I’ll do maybe one, maybe two in the middle of the evening. The hardest stuff always goes in the middle for fairly obvious reasons. You know, everybody’s there, people are warmed up mentally and physically, and mental fatigue hasn’t started to set in. But for the most part, I look for dances that I call easy but different. Easy enough that that everybody there can get them, even the first timers, you know, at a dance where most people have danced before can get dragged through somehow, but different enough from each other and from perhaps other callers’ repertoire that the more sophisticated dancers won’t get bored and won’t say, oh, this is just the same old thing over and over. It’s harder if it’s an all contra evening, a modern urban contra event where people want a dozen contras and they’re all either duple improper or Becket, you’ve got the boy-girl, boy-girl or lark-robin, lark-robin circle of four. And you have to come up with new ways to manipulate them. But staying in that framework, I enjoy it more when I can stick in some variety, squares if the numbers work out right. Four by fours are good because you don’t need four couples. You only need two to get in and you can do a lot of the same things that you can do in squares. You can take advantage of the fact that you have four couples. Sicilian circles or progressive circles, couple-face-couple around the room if you have room for something like that, again, it opens up the patterns a little bit and even though it’s just a contra with the ends bent back around to each other, it has a different feel. And, of course, circle mixers. One of my favorite kind of dances as a dancer are circle mixers, and I always do at least one. And if it’s a non-dancer event, I’ll probably do several.

Why Variety?

Mary Wesley As you’ve talked about your experiences over time with calling you’ve mentioned multiple times this shift or starting out at a time when variety was the norm. That it might be called a square dance, but it was fully expected that you would do any number of different formations in that space. That’s a familiar storyline to me now, I sort of seem to walk the cusp of getting started dancing in sort of the mainstream contra dance world. But just because of different connections and exposure that I had and maybe just my personal taste and preferences, you know, I certainly have a deep love for that sense of variety. That’s why I love going to dance weekends where there’s more space to try different things. Or, you know, the Ralph Page Dance Legacy Weekend, where we have often crossed paths, and that’s been really influential to me in kind of broadening my scope and having a way to experience kind of the history and the roots of some of the dances that we’re still doing today and I like having that resonance, having a sense of what’s happened in the past and how it is still repeating itself and changing in different ways. It’s such an interesting process and one that it feels hard to talk about without getting too abstract. I know it’s on a lot of people’s minds, this, I forget what you called it, the specialization of…now a contra dance really means pretty much just contras for the most part. Maybe one mixer, maybe one or two squares, a couple dance at the break. That’s kind of it.

Tony Parkes I think one thing that makes me think of 12 contras and a waltz and maybe a hambo as an aberration, is that traditionally going back as far as I can remember and as far as my printed sources seem to remember, the norm was never to have all one kind of dance. I’m thinking mostly of events that were billed as square dances because the whole contra thing seems to be fairly new. But where group dances were done traditionally, either squares or contras or both, they would never—and I use the word advisedly, obviously, you can always find an exception—but I would say 99.99% of the time an evening would be at least two kinds of dance. Almost everywhere that I’m aware of when something was advertised as a square dance, it would be squares alternating with the locally popular forms of couple dance. But you would never have like three or four or five of the same type of dance in a row. I suppose it makes it easier to learn in a way if you only have to learn one, set up one framework. But I find it limiting as a caller.

Mary Wesley It’s a conundrum to me as a caller, and I feel like I hear from other callers and dancers about this too. You know, if we get specialization at the level of a dance series…so I mean, now we have a lot of just contra dances…they are mainly contras. We have the Dare To Be Square movement. There have been some great moments of a new generation of dancers and callers and musicians bringing square dance back…

Tony Parkes I’m excited about that, probably because it’s squares, which I have always loved. They were my first love, and partly because it’s young people and I feel the same way that my mentors did when I got into calling. It’s so great to see the next generation or the next, skipping a generation or whatever, but the people in their teens, 20s, early 30s, really getting into dance.

Mary Wesley Right. It’s created, I think, a lot of energy and interest. I’m thinking of the Washington, D.C. area has a big square dance, the Tractor Tavern out in Seattle and the Dare To Be Square weekends have happened across the country. So there is this feeling that while people who love who really love the contras, they can go to the contra dances and people really love squares, they can go to the square dances and to me, the conundrum is, as a caller, how much do you bring your personal taste and preference? And I’m seeing you in the general, you know, if the caller feels like there’s a big value to variety, but they’re in a space where the dancers don’t want that as much. What do you do? How much do you serve the dancers or give the dancers what they wish?

Tony Parkes This is something I’ve wrestled with all my career is, how much do you give dancers what you perceive they want and how much do you give them what you think is good for them,

Mary Wesley Right. And who are we as callers to say that?

Tony Parkes …because nominally, the caller is a leader, but in practice, the caller is hired by a group to please them. And it’s a well-known phenomenon going back to the square dance boom that the most advanced dancers, the most sophisticated dancers, the dancers who want the trickiest stuff are also the most active club members who tend to be the officers who have the power to hire and fire the callers. And I think that’s true even when the group doesn’t bill itself as a club with officers, I think there’s a prevailing mindset in a lot of contra dance groups that they want a certain type of program, and so they tend to hire the callers who will give them that. I know there are groups that I would never get hired by, and that’s OK because I would not enjoy calling the kind of program they have in mind.

Mary Wesley Yeah, I guess I’m curious if you can say more about how you’ve grappled with that tension and how do you decide?

Tony Parkes If it’s a group I haven’t called for before, I sound them out, the organizers or whoever contacts me, I say I like a certain kind of program and I think the caller by virtue of his or her job description should have the leeway to use certain things or not, depending on the numbers on the floor and depending on the caller’s reading of the group mood. I don’t say the following, but I think that if you don’t agree, then we’re probably not a good fit. I think maybe once, maybe twice in my entire career, I have gotten the impression that they changed their minds and didn’t have me because they didn’t like what I was saying. But, you know, I would say more than 99 percent of the time they went along with my idea. I almost always, I find that we can reach an understanding that I will have the authority to use whatever formations I see fit. But in return, I agree not to abuse that power. You know that I’m not going to force squares on them just because I love squares and I like the dynamics that goes with them.

Mary Wesley What do you think is lost in an evening that doesn’t have some variety?

Tony Parkes Well, I’d have to think about that. But one aspect comes to mind immediately, and that is when they know the next dance this is going to be a contra they grab a partner, they line up partners, they book ahead. They will ask somebody in the middle who is their neighbor, in the middle of a dance, “Do you want to do the next one or do you want to do the third one? Or do you want to do the first one after the break?” They line up partners in advance, and as soon as one dance is over, they line up for the next one. I do think that having just one kind of dance in an evening fosters this mentality of just being there for the dance rather than the people.

Mary Wesley All of these questions and conversations are sort of based in such…such understandable human emotions and impulses too, that I can completely understand people wanting to dance with a friend group or with a dancer at their same level. It’s always just a delicate balance moving between that space of an individual experience and then a group experience.

Tony Parkes I have trouble processing it when some people just will not let in the group mentality. I had one dancer who I asked to dance and who was booked ahead for like six dances. I said, why do you feel the need to book ahead in such proportions? And she said, I want each dance number to be a peak dancing experience, and the only way I can assure that is by booking partners. That bothered me that they would not set aside even one 10-minute time slot for asking a new person to dance, bringing somebody into the group because, you don’t have no beginners and in a few years, you won’t have no dancers.

Mary Wesley Right? How do you make space for a little bit of unknown, an unknown factor in your dance experience or giving a new person a peak experience?

Tony Parkes I mean, I will forever be grateful to the people who put up with me when I was a kid, not just as a budding caller, but as a dancer who probably thought I knew everything. I mean, I did have a good grip of the technical side of both dancing and calling fairly early. But there’s always something new to learn.

Writing Square Dance Calling: An Old Art for a New Century

[ Clip of Tony calling the Kitchen Lancers, Dare to be Square Syllabus 064 ]

Mary Wesley I would also love to hear a little bit more about your square dance calling book. I wonder was it a pandemic project?

Tony Parkes It turned into one. I had the idea for it long before that, but I was able to use the pandemic to advantage.

Tony Parkes I had the idea for the book some years before. In fact, I recently found some notes I had made in 2016, so five years before I finished the book and about three years before I buckled down to work, talking about what I wanted to put in it and some first drafts of some of the sections, and also some correspondence and email where I was telling people what was going to be in the book. I had hoped to have it out within a year or so.

Mary Wesley Nice, and so and what was the impetus?

Tony Parkes For the book in the first place? Well, that the contra book had done well, that the people had accepted it and that there was enough interest to get it reprinted after 18 years because the first edition was 1992 and the second edition was 2010. So it was the fact that the contra book had been received well and sold well, combined with the fact that there is a shortage of caller mentors out there. And I found in my travels that there are people who are callers who would like to do more squares and do them better. And they don’t know where to begin. They don’t know where to find square dance material. And when they do find it, they don’t know how to pick and choose the ones that are going to appeal to contra dancers or to whatever group they’re working with. And of course, they need the practice in order to get good enough so that the dancers will hold still for the squares. So I felt like there was an opportunity here. There was a gap that I had the knowledge and the experience and the expertise to fill, at least partially. And of course, I had the writing skills and my hobby within a vocation is dance history and collecting books and recordings. So I knew what had been done in the past. I was able to draw on it and also the fact that there has been very, very few books on traditional squares for the last 20 or 30 years. I can think of two offhand, and that’s about it. I felt like there was room enough for what I intended to do. The book turned out bigger than I had anticipated. I wanted it to be a lot like the contra book, but with relatively more actual dance material than there was in the contra book. I didn’t put a lot in the contra book because there are a lot of collections of contras out there, and now people are finding them online. I thought that what was needed at that point was talking about the mechanics and the philosophy of calling more than putting the actual dances in the book. Whereas with squares, as I said, most of the good books are out of print and people don’t necessarily know what to look for and when they get hold of a book, they don’t know what to look for within the book. So I wanted to basically give away the farm, give people my square dance repertoire in the book. So I’ve got 50 figures and breaks with two call charts for each one. Just as in the contra book, one showing where the movements go relative to the music and the other showing where the words of the call go in relation to the music. And then I’ve got the usual discussing the basic movements in depth. I tried to shorten the theory and the mechanics chapters a little bit, figuring anybody who wants more can get the contra book or maybe already has the contra book, but it’s still turned into a 500-page volume. I’ve got a glossary where I try to put most of the important or interesting words that were used during the boom of the ’50s, as well as a few things that are more recent. And it ended up with, I think, 600 plus entries in the glossary. I have about 90 capsule reviews of square dance books, mostly from the 1950s, because I figure it’s not going to help if I just list them. So I decided I needed to say a little about each so people can find what they’re looking for. I wanted it to be a one-stop shop but not to be the be-all and end-all. I definitely wanted to point people beyond what I have to say to see what the experts of the past have said and done.

Mary Wesley A bit of a roadmap for folks. As you said square dancing is a very broad umbrella, there’s a lot of different specificity within there. Can you kind of draw a container around which part of the square dance tradition does your book kind of address or which parts?

Tony Parkes Leaving aside modern so-called Western, although it’s not really western, modern square dance as done in clubs. If you leave that aside, because it’s a very different mindset in some ways, looking at the rest of the square dance world outside the clubs, I divided it into three main parts. One is what I call survival dances, and there are fewer of them every year. But you know, there are still a handful in the Northeast, and I think there are some in the southern mountains, not sure about the Midwest and the West, but dances that have seemingly always been there. If the caller dies or retires, another caller will step in. And these are dances that are often sponsored by the local fire department or a local service club like Rotary, as a fundraiser and as a social event and it’s more about the socializing than it is about the dance. And typically, the caller will have a limited repertoire. And as I said earlier in the case of singing calls, the dancers will dance without prompts because they know all the figures. The dances on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia are like this, except that most of them don’t have callers. The dancers do the same three numbers every time they get up. But there are dances in Canada that they work like this too where the caller will just know a few dances and dancers are happy to do those dances over and over because it’s not about learning, it’s not about a hobby, it’s a social occasion. So that’s what I call survival dances.

And then there’s the old time, the new old time dance network, the Dare To Be Square network which grew out of the old time string band music community where people would have all the old time sessions, old time jams and music festivals, and somebody somewhere along the line said, Hey, wait a minute, you know this is traditionally dance music that goes hand in hand with the dance. It’s such an integral thing, and we don’t dance at a lot of these events, so let’s dance. Some of it may be also a reaction to contra dancing, urban contra dancing, getting more insular and more set in its ways. Now you’ve got, as you mentioned, Tractor Tavern and the D.C. Square Dance. You know, there are several on the East Coast and in the Mid-South, there are several on the West Coast. It’s not the kind of formal network that you have with CDSS but people do communicate, they do keep in touch. And there are the Dare To Be Square weekends that are held in several places once or twice a year. So that network, that style, I think is still on its way up as opposed to contra dancing, which has kind of plateaued. So you’ve got the survival dances where they either don’t know about or they’ve chosen to ignore the square dance clubs and CDSS and Dare To Be Square. They are their own, they’re not even a network. They’re just there. They are part of the local social community, just like a Rotary Club or a church supper or what have you.

So the third kind of more or less traditional square dance is eclectic. It’s the kind of squares that people do at contra events. It’s the kind of callers who stay in touch through groups like CDSS, but who don’t want to limit themselves in terms of style. I’ve coined the term neo-traditional, and that’s the term I use in the book. I think it was Nils Fredland, when he put together a square dance page for the CDSS website, who called it traditional style modern squares. And to me, it’s the same thing, the kind of squares he was talking about are the kind of squares that I refer to as neo-traditional. And by that, I mean that they are eclectic. They borrow some aspects from all the different regional traditional styles and even a little bit from modern square dance but they’re not exactly like any one of them. I’ll just borrow from my book here: from Southern Mountain and traditional western squares they take the exuberance, the fast tempo, the circular swooping figures that you don’t see in other styles. From New England or northeastern style, you’ve got the close connection between the dance and the music. You’ve got the buzz-step swings, which you don’t get in southern or traditional western dances to the same extent. And you’ve got the rich tradition of singing calls, which were originally a northeastern thing as far as I can tell. Then from early modern squares, late ’40s,1950s, what’s sometimes called transitional square dance, between traditional and modern, you’ve got the move toward all-active choreography, more people being in motion more of the time. You’ve got the emphasis on doing as much as possible with existing basics, rather than inventing new calls that have a specific meaning. And from later modern square dancing from the ’50s on to the present, the playfulness of callers improvising and dancers matching wits with the caller that actually predates modern square dance. Ralph Page was doing that back in the 1930s or ’40s. He got his inspiration, partly from the traditions of the 1850s to the 1890s. In this interview, we haven’t gone into dance history much, but there’s hardly anything new under the sun. Callers improvising and callers challenging the dancers goes back, at least to the mid-1800s. So that’s the kind of dancing and calling that I focus on in the book, which I call neo-traditional, I don’t say a lot about southern sets because I’m not an expert on them. I don’t have a lot of experience with them. I love them, but I point people to their callers and authors who can give them the real deal. As far as survival dances go, they are more a social phenomenon. You know, what they have in common is that they are a social event and the dance style is whatever is traditional in that area. So it’s not something that I can write about as a separate style. What I’m dealing with in the book is more or less phrased squares as opposed to just call and let the chips fall where they may. I suspect that a lot of people who get the book are going to be contra callers. So what I’m trying to do is to give people the courage to try improvising, even if it’s just a break here and a break there, and to give them the technical knowledge and the technical skills to be able to sound as though they’re freewheeling when they’re actually calling a lot like the way they would call a contra.

Closing

Mary Wesley I love that strategy. I’m excited to learn about that. Well, I’m so excited that that book now exists, and I will certainly be adding it to my collection. Well, I have a few closing questions that I have been asking everybody. One is how do you keep your dance collection? Do you have dance cards, notebooks? Have you gone digital? What’s your kind of cataloging system?

Tony Parkes It’s in a state of flux. I’ve never been a big fan of cards, partly because memory is one of my strengths, so I haven’t felt the need of them as much. And partly because I was always afraid I would lose some and then I wouldn’t – This was before computers, because Beth keeps hers in the computer where she can print cards or she can print all sheets of them. So she doesn’t have to worry about losing a dance and never finding it again. But when I was using handwritten or typed cards, I was always worried that I would lose some. So I tended to write them on letter size sheets, I would put 8 or 10 or 12 dances on one sheet. I have what I call my clipboard, although it’s a letter size album originally made for salespeople where it has clear, transparent pages that you could put back-to-back stuff in and that was for your catalog pages, so you could show the prospect your product line. And then there was also a place to put blank sheets of paper, just a little holder. And so I’ve used that over the years, I’ve kept my repertoire in the clear pages and put my log of what I call in the place for the loose sheets. I’ve experimented with cards a couple of times and never have been really comfortable with them. Most of my dances, either they’re on those sheets that I made up or else if it’s something I don’t call very often, I know where to find it in one of my books. I say my books, I don’t mean the ones I’ve written necessarily, but you know, my library. There are some dances that I do so often and know so well that I don’t think I have them written down anywhere. Most of the ones I do at one-nighters are just up there. I don’t have a storage system that I can recommend to anybody and I say as little as possible about that in my books.

Mary Wesley That’s one of the reasons I’m asking. I’m curious to ask different callers about it because I think everybody has to find a system that works for them and there’s various factors that go into that. And then another question is, do you have any pre or post gig kind of rituals or routines that you go through to get ready and prepare for a gig or to kind of wind down afterwards?

Tony Parkes I try to warm up vocally before the dance. Often in the car, if you’re in the car, you have to be sure that you are projecting correctly. It’s easy to be, you know, sort of vocalizing inside your head. Or conversely, if there’s too much ambient noise, you can strain your voice by trying to hear yourself. Once you get into the groove I think it helps more than it hurts. When I get where I’m going, especially at one-nighters, but in general, when I get to the hall, I try to find a place where I can be by myself and just center down, as the Quakers say, just discard everything that’s going on in the rest of my life. If I’m tense about anything, just let it go for the next four hours. The three hours of the dance and the pre and post times, the set up and tear down if I’m doing sound. If it’s a one-night usually I’ll arrive and check in with the organizer and set up the sound and maybe do a little bit of a sound check. And then I’ll go off and then center before I’m on for the people. Afterwards, I’m often hungry, but depending on how far I am from home, either I’ll have some sort of snack especially if I’m an hour’s drive or more from home to keep me awake on the way home. But I’ve learned that if I’m about to go to bed, either because the gig is close to home or because I’m out of town and staying over, it doesn’t do to eat a lot no matter how hungry I am because it’s going to keep me awake and screw up my rhythm. Also, it’s also a temptation to talk shop after a gig, especially if I’m on the road and I’m with experienced dancers or other callers and again, I have to be careful that I don’t strain my voice by talking too long at a time and also being socially on when my body is telling me is it’s time for bed. So I don’t have a really good post dance routine that I fall into. Something I’m still working on.

Mary Wesley Well, it sounds like you have an awareness of the different things that you might need. And yeah, that’s always the challenge that depending on the gig, there’s any number of logistical things that could interrupt a routine so we have to be flexible. My last question is just my own little piece of sociology that I’m curious about with other callers and not everybody knows this about themselves in these terms. But if you do know, do you identify as an introvert or an extrovert?

Tony Parkes Oh introvert, definitely. That doesn’t necessarily equate to being shy, although historically I have been a shy person as well, and an introvert is somebody who recharges in solitude as opposed to an extrovert who surrounds themselves with people to recharge. It doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy being in company. It just means that every so often I need to just get away and recenter. I think a lot of actors, a lot of entertainers, a lot of performers are introverts and they put themselves into being there for their audience or their people. But then they need to recharge in their own way. And of course, it’s well known that a lot of actors are shy people who are able to act because it is an act. I tell the story in both my books – in this new squares book, I come out and admit that I was talking about myself in the contra book – that I was painfully shy. The way I was able to start calling was to tell myself, this is a part I’m playing, this is not me. Over the years, it became more and more of the real me, and it helped bring me out of my shell. But it also meant that I could put less conscious effort into it. When it came more naturally, I could focus on other aspects, some of the technical stuff and some of the looking out for the well-being of various people in the hall because it wasn’t such a conscious strain, conscious effort to overcome my stage fright.

Mary Wesley That’s so interesting. So you kind of lived your way into that role? It sounds like calling is very intertwined with just who you are as a person.

Tony Parkes Oh, definitely. It literally kept me alive at one point when I was really depressed and sleeping 16 hours a day and headed for 24. I would go out to the local dances and if it hadn’t been for having to be in a certain place at a certain time for the dance, I don’t know what would have become of me.

Mary Wesley Thank goodness we have that dancing and thank goodness we’re hopefully, cautiously, carefully making a return. It’s nice to hear that you have some gigs coming up, and I hope that we will cross paths at some dance some time again before too long.

Tony Parkes Sure, we will, Lord willing and the creek don’t rise.

Mary Wesley Absolutely. Well, Tony, thank you so much for your time today. It’s been so great to talk.

Tony Parkes Thank you, Mary. It’s been loads of fun. It always is talking about what I love with other people who love it too.

[ Clip of Tony calling The Merry Go Round, Dare to be Square Syllabus 157 ]

Mary Wesley A big thanks to Tony for taking the time to chat with me for this episode and sharing so much wisdom and history with us. And dear listeners, if you’re feeling like wait! I want more! Well you’re in luck. Next week we’ll be releasing a special bonus episode in which Tony will take us on a little tour through his vast collection of dance caller recordings. This was one of my favorite parts of our interview and I wanted to feature it in its entirety, so be sure to keep an eye on the From the Mic podcast feed where it will soon appear. You can also hear a few more excerpts from my interview with Tony that didn’t make it into this episode in our show notes at podcasts.cdss.org, where you can also find more interviews with more callers!

Thank you for listening to From the Mic. This project is supported by CDSS, The Country Dance and Song Society and is produced by Ben Williams and me, Mary Wesley.

Thanks to Great Meadow Music for the use of tunes from the album Old New England by Bob McQuillen, Jane Orzechowski & Deanna Stiles.

Visit podcasts.cdss.org for more info.

Happy dancing!

Ben Williams: The views expressed in this podcast are of the individuals and do not necessarily reflect those of CDSS