Videos

The following videos are from the CDSS Lifetime Contribution Award ceremony for Brad Foster held on October 24, 2015, at the Orange Town Hall, Orange, MA.

David Millstone speaks at LCA Ceremony for Brad Foster:

Ellen Judson speaks at LCA Ceremony for Brad Foster:

Tom Kruskal speaks at LCA Ceremony for Brad Foster:

Robin Hayden speaks at LCA Ceremony for Brad Foster:

Laurie Anders & Andy Davis perform a musical tribute to Brad:

Gene Murrow speaks at LCA Ceremony for Brad Foster:

Sharon Green speaks at LCA Ceremony for Brad Foster:

Presentation of the LCA to Brad Foster:

Brad Foster accepts the LCA from CDSS:

Andy Davis leads a song at the LCA ceremony for Brad Foster:

Brad Foster: A Calling Career—Interview by Tom Kruskal

Brad Foster, CDSS’s Executive and Artistic Director Emeritus, is a 2015 recipient of the CDSS Lifetime Contribution Award. He was interviewed by musician, dance teacher and longtime friend Tom Kruskal who himself was a recipient in 2010. Their conversation was held on June 27, 2015, at Brad’s home in Shutesbury, Massachusetts.

Getting Started in Dance—The Mary Judson Years

TK: Why don’t we go through your dance career chronologically. I know remarkably little about your time in Southern California with Mary Judson1, before Berkeley, so I would just love to hear how you got connected with her, and with your peers who were around, like Lydee Scudder2, and Mary’s kids Molly and Ellen. How did that happen?

BF: When I was in middle school, just before I went into high school, I was in a high school play, and at the end of the play some of the cast invited me to go to “The Museum.” I thought they were crazy because I thought they were talking about going to an art museum, and it was already after 9:00 PM when a museum would have been closed. The Museum turned out to be a folk dance café, and I fell in love with that.

The Museum also was where Mary Judson taught. Through folk dancing I met Lydee and then her sister Alice, and Mary’s daughter Ellen, all of whom were in my high school. Through Ellen and The Museum, I then met Mary, who taught English country dancing there and around town. I started dancing regularly, rode my bike to all the events that I could go to. And I did a little bit of dancing in school too. I remember Ellen teaching me some morris dance figures out in the courtyard of our high school. I even got assigned the role of calling a dance for a school performance. It wasn’t really calling because everybody knew the dance; calling was just part of the performance. But I think that assignment set the stage for my calling later on. So through the four years of high school I did English country and international folk dance, and a group of us always went to the Southern California Renaissance Faire and performed. Sometime during those years I met you, Tom, but I can’t remember where or when. I know I was up in Berkeley once or twice, but you also came down to do a workshop at one time. Then in 1971, just before my senior year in high school, I wandered across the country and ended up at Pinewoods3 on visiting day! I came as a visitor, but somebody (I assume it was Mary Judson) had made arrangements for me to stay, and so I stayed the rest of the week.

TK: But you’d heard about Pinewoods. Mary had been coming with her kids.

BF: Yeah, Mary had been coming with her kids. Ellen had told me all sorts of stories about Pinewoods, about May Gadd 4, and the bush patrol. [Here Brad puts on a high pitched “May Gadd” voice:] “Rumpety tump!” 5 I’d been visiting Alice and Lydee Scudder at their grandparents’ house in Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire, where I first ran across Duke Miller6 and that style of contra dancing. Alice was heading down to the Cape to visit relatives so she drove me to Pinewoods and dropped me off. That was an unusual summer—there I was from this private high school in Pasadena, with three of my school friends—Ellen, Patty [Haymond], and Pam [McGrill]—also there.

College Years in Santa Cruz and Berkeley

TK: So then, what about college?

BF: Like most of my friends in Pasadena, when I finished high school I wanted to escape and go somewhere else. I looked at Prescott College in Arizona and some other places but ended up choosing U. C. Santa Cruz. I wanted to study natural history, but they also had an international dance program. I saw you in that period, too, because Santa Cruz was close enough for me to occasionally get to your dance in San Francisco.

In Santa Cruz I took dance classes and I also, rather quickly, got a job teaching folk dancing. The regular folk dance teacher, Marcel Vinokur7, who came over the hill from Palo Alto to teach, took a sabbatical soon after I arrived—so in his absence I stepped in and taught. My first class was in international folk dance, but it quickly got turned into an English country dance class. I would come up to San Francisco to go to your dances and record the music and bring it back. There was also a square dance caller who I knew as “John the bass player.” I never learned his last name. He had learned his square dances from the pastor of a church in Oakland, who had learned them somewhere in the Midwest. John called squares with a bluegrass band, but then he graduated and left, and so I filled his gap too. That was the beginning of my square dance calling.

TK: So did you have any contact at all with CDSS National during that time?

BF: Well, I certainly knew about CDSS. I’d been to Pinewoods already, and they were the source of dance books and records. I also remember getting big scholarships—this was later on, when I was coming as a camper in 1975—to come to camp, and I ended up spending about as much as I would have on the camp fees buying books because I had no dance library. I may have first met Jim Morrison8 at Pinewoods; I know that I saw him there in 1971, because that was the summer he and Marney got together. Jim was from Oakland; I can’t remember if I met him in California before I went to Pinewoods, but by the time I knew him, he was working in the CDSS office. In 1974, I wrote to him at the office, hoping to come to camp. That was the year Pat Shaw9 came, but my letter to Jim got lost, and by the time I figured out what had happened, camp was full and there was no way for me to get in, so I went to Stockton Folk Dance Camp 10 instead. You had been to Stockton.

TK: Yes. I left California in 1974; I’d taught at Stockton maybe in 1972, and Nibs Matthews11 had been there the year before me.

BF: And Nibs was supposed to come back in 1974, but he cancelled, and Bob Parker12 came and basically took all of Nibs’s notes and tried to figure out what Nibs meant so he could teach from Nibs’s material. (Laughs)

TK: Yeah, I came the year after Nibs, sort of as a follow up to Nibs. Not a particularly successful gig for me.

BF: That’s when you were using Chuck Ward’s13 double-tracked harpsichord recordings, the 45s?

TK: Yes, right. Chuck set all that up for me.

BF: He said he’d been supposed to record the tunes with Lea Brilmayer14, but right when the recording was supposed to happen she went off to Mexico. So the recording was double tracked with harpsichord and harpsichord.

TK: At Stockton we had to provide a set curriculum with recorded music and printed sheet music, and we had to have discs to sell. When I left California in 1974, Chuck and I decided you should teach, and we asked you. Where were you at that point?

BF: Well, I started at U. C. Santa Cruz in 1972, and I lasted about a year and a half, and then started a long process of transferring to U. C. Berkeley. I stayed in Santa Cruz and taught dance and did carpentry and gardening, and then in 1975 I transferred up to Berkeley, just after you left. I finished Santa Cruz, moved to Berkeley, and took over your dance. A couple of years later Nick Harris, who had been running the Stanford contra, graduated and left, so I took over his contra dance too.

TK: Tell me something about the Bay Area Country Dance Society. It’s gotten all built up now, but what was it like then? How much of that growth were you there for?

BF: When I came on the scene, you had your dance. The story I tell is—this is one of those stories that I’m not sure is true—but what I remember hearing is that you met every week on Sunday, with a very tiny crowd, and the dance stayed like that until the crowd finally got big enough, and then you switched to once a month.

TK: Is that right? I don’t remember that.

BF: And then you moved it from San Francisco across the Bay to Berkeley because Chuck found a different hall. Then I came in and switched the dance to twice a month, and it has stayed pretty much like that ever since. Your dance, which later became my dance, was the only English dance for a while. At some point before 1975 Nick Harris started the contra dance at Stanford, and a few people did traditional style squares as well. At some point I met a fellow whose grandmother was connected to the dance department at Stanford University. He told me that May Gadd used to come out once in a while to teach at Stanford . But as far as I can tell, her visits had no lasting impact; nothing grew out of them.

So, in 1975 I took over your English dance, and I started a short-lived contra in Berkeley; I later started another contra in Berkeley and an English dance at Ashkenaz15 that didn’t last very long. I started something in an art center on a pier in San Francisco. Meanwhile, Bruce Hamilton16 moved to Palo Alto and started an English dance in San Jose. Bob Fraley moved to the Bay Area and started the first English dance in Palo Alto. So, things started cropping up. Kirston Koths moved in and started a Berkeley contra that kept going, unlike mine. When my contra in San Francisco failed to keep going, Charlie Fenton started another one in California Hall—that dance moved out to St. Paul’s on the West End and has been going for a long time. It just felt as if a couple years after you left everything exploded, and suddenly there were all sorts of new people. The same thing happened when I left—as soon as the vacuum was there, all these people filled it, and lots more stuff happened.

Founding the Mendocino Country Dance Camp and the Bay Area Country Dance Society

TK: I assume the Bay Area group now has a board of directors and an organizational structure that wasn’t there when you left, or had that started?

BF: I feel like I created that. You had a single English country dance in San Francisco, run by you, Chuck Ward, and Nora Hughes, and that was the English Folk Dance Society of San Francisco (or some similar title).

TK: Yeah, we had some official structure. We might have even been a CDSS Center.

BF: Yes, you were a Center17, and you were very early in getting onto the nonprofit group exemption. I learned all that later when I became CDSS Director. But I think you had no appreciable organization, no bank account then.

Then, in 1979, I was hired to teach English country dancing at the Mendocino Folklore Camp, an international folk dance camp held at the Woodlands in Mendocino. I loved it so much that, with my first wife Jenny, in 1980 we created the English dance camp at Mendocino. In 1981 we added the American week. After the first year began, we started thinking that there should be an organization. That’s when we created BACDS, and we merged the earlier organization, the English Folkdance Society of San Francisco, into it, and also brought in any of the contra and English dances that wanted to join us.

Some people thought I was crazy to create BACDS. They said, “You created this camp. Why are you giving it to BACDS?” Even though at that time I had no intention of leaving California, I thought the camps and dances should have permanence, should be more than me, and so I created the board and all that.

I remember very early on talking the board into hiring me as the part-time paid administrator of BACDS. It was about a one-tenth time job. My first task was to learn how to do accounting, then to create an accounting system, and finally to figure out how we stood financially. A couple of months later, I came to a board meeting and said, “Well, I have two things to report. The first one is that I finished that task of putting a financial system in place, and I can tell you your financial standing. The second one is, ‘I quit,’ because I can show you that you can’t afford to hire me.” And it went back to being a volunteer organization. Even that little bit of time was more than BACDS could afford back in those days.

TK: Before we move on and launch into CDSS, is there anything else about your early career that you wanted to get in?

BF: I had learned morris dancing in high school before getting to Pinewoods, and learned more at Pinewoods. I think you taught some morris or sword at the dance weekends, too. When I moved to Berkeley, I started a morris team, the Berkeley Morris. We first met in what was then the Ho Chi Minh Park. I wanted to be the Ho Chi Morris Men but no one else would agree to that.

Then, starting around 1977, I began doing some small calling tours, and by 1980 I was doing bigger tours. In those days it was primarily contras and squares—English groups couldn’t afford to pay enough to cover travel costs. My first tours were on the East Coast, in New England, and then I started touring in northern California, plus a little bit of Oregon and Washington.

Moving East — Joining the Country Dance and Song Society

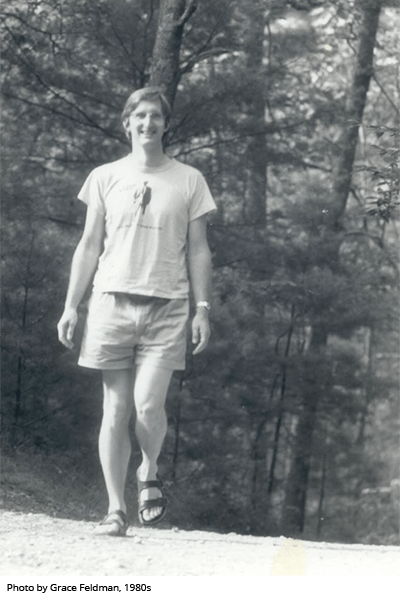

[media-credit name=”Photo by Grace Feldman” align=”right” width=”400″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

TK: So tell me about moving east, and how that happened. Jim Morrison had stopped working for CDSS and moved [to Virginia]. CDSS was struggling with a series of short-term Executive Directors.

BF: Gay [May Gadd] had been National Director for decades; I don’t remember exactly when she stopped. 1974-ish? Then Genny Shimer18 came in; she wanted to do it for only a year, but stayed maybe a year and a half. Next Jim Morrison stepped in for a couple of years, at which point he moved from New York City to Virginia but stayed on as Artistic Director, and Nancy White-Kurzman served as Executive Director for a couple of years. After Nancy, Bertha Hatvary came in as Interim Director and then was hired as Executive Director for a while. Bertha’s biggest strength was the newsletter and publicity. At some point they started looking for somebody new, and approached me. By then I had already been organizing lots of weekends, and had started and run Mendocino for a few years.

Then someone asked me if I’d like to work for CDSS. At first, I didn’t take it seriously. Meanwhile Jenny received a job offer from a school in Greenwich, Connecticut. I had graduated a few years earlier with a BA in Architecture from U. C. Berkeley, and was working as a draftsman in an architect’s office. In late 1982 a recession hit, and my architecture boss kept telling me he was going to lay me off. With the job at CDSS as a possibility, and Jenny’s solid job offer, we moved east. After we moved, I interviewed with CDSS, was offered the job, and began as the National Director on February 1, 1983. The job title was later changed to Executive and Artistic Director.

TK: Tell me about the scene at CDSS when you came into it, what your reaction was, who the mentors were there. I know Sue Salmons and Genny Shimer were there. John Hodgkin was Treasurer, right?

BF: Yes, John was Treasurer, Sue was Chair of the Executive Committee 19.

Sue worked so hard. In later years I realized she quietly had served as interim Executive Director in the many months between when Bertha Hatvary left and I came in. Sue never had the title, she never asked for recognition, but she came in every week and just made the office run. She was always there, working the phone all the time. I had a lot of respect for her energy and for what she wanted to do, even if I didn’t agree with all of her decisions or the methods.

So Sue was there, and Kit Campbell was office manager. Genny Shimer was also around; she was the quiet person on the artistic side. I had such reverence for Genny, for her teaching, and for her sense of where CDSS ought to go artistically. If I had a question on artistic matters I would go to Genny or possibly to Jim. I knew Jim better, but he lived a lot farther away.

[And] John was Treasurer. I learned an awful lot of nonprofit accounting from John. He also had a philosophy. When he was a young man getting into accounting, one of his bosses gave him a financial leg up and said don’t pay me back, just pass it on—give a similar gift to someone else when you can. That became a model for us at CDSS, one we couldn’t always follow. The idea was that we would support you now in the hopes that you would support someone else later, and we would just keep lifting people up.

TK: So by the time you’d been there three years or so, you were developing your own opinions about what things were working and weren’t, what the vision was or wasn’t, and what your vision might be. Tell more about that.

BF: I remember very early on, I told somebody that I was the director of CDSS, and he said, “Oh, you’re the New York Society.” That was this CDSS member’s image of what CDSS National did—it focused on New York City. And there was some truth to that. There was also Pinewoods, and some others might have said, “You’re the Pinewoods organization.” So there was Pinewoods, and then there were NYDAC (New York Dance Activities Committee20) and the Folk Music Club21, and also weekends at Hudson Guild in New Jersey, but the main focus was on New York City activities as a showcase for the nation. In my interview before I got the job, someone asked me what I thought of NYDAC and the Folk Music Club. I had already heard some mutterings and disagreements about what was going on with them, and I said, “Well, we’re a national organization. The local organizations should make their own decisions.” And I heard back “You can’t say that.” And I took that literally—I stopped saying it, but I didn’t stop thinking it.

When I came into the job, some people expected me to revitalize the English dance in New York City because I was a teacher as well as an administrator. But my focus for CDSS was national, and in my first ten years I used my contra touring, which I was doing quite extensively then, to get myself all over the country and to build up CDSS’s visibility and membership. The membership of CDSS grew rapidly, and perhaps doubled, in those years. CDSS went from an organization that had been largely English dance based, with some folk music and some contra dance, to one that grew particularly on the contra dance side, partly because I was all over the country calling contras but also because we were riding the wave of contra dancing that was sweeping the country.

Then our rent in New York doubled—our rent in this grungy top floor space in the garment district. So we looked all over New York City and found that, even at double the old cost, it was still the most reasonable place we could rent in NYC. Bertha Hatvary, who was still involved, said, “You should move Sales to New Jersey to save money because it’s cheaper.” She didn’t mean move the whole office out of New York City, just the sales department. Then, someone at our Leadership Conference in the South said, “This is crazy. Your rent is so high, come to where we are.” That started the whole brouhaha about whether we should move or not, which lasted a while. Eventually we did move [to Massachusetts]. I looked at it as a question of where we could find something we could afford that was close enough to serve Pinewoods, our major program. It was a big political hassle, moving.

TK: So it was an economic decision at its core. I remember you were interested in living somewhere else, and I know that Jim Morrison wanted to live somewhere else when he worked for CDSS. Back when he wanted to move, he had suggested moving the Society, but there was no question then that a move was going to happen. How much of the Society’s move from New York do you think was prompted by your wanting to move it out?

BF: I’m not sure what would have happened if Jim had not already tried to get CDSS to move [in the 1970s]. Jim tried and failed, but his attempt set the stage for another try. I wanted to move because my salary was so low compared to New York City costs. I had gone looking for a place around New York where I could afford to buy a house, and the closest was an hour and a half drive from the city. Everything was very expensive. So I wanted the move in a personal sense. I remember saying to Sue Salmons and Mary Judson that I couldn’t afford to keep being Executive and Artistic Director in New York and would happily help them find a new ED if CDSS preferred to stay in the city. So I was looking both for a cheaper place for CDSS and a cheaper place for me and for the staff, a place where the current salaries wouldn’t be so far out of line. They would be low instead of abysmal.

TK: The other aspect, of course, was that to make CDSS more of a national organization—a move from New York City to almost anywhere would potentially help.

BF: That’s true. Even though that wasn’t the main thing on my mind, I thought it wasn’t a bad idea either. CDSS had become ingrown and it needed to grow and change. Moving was one of the biggest ways to grow and change. We lost a number of members in New York City, but we gained many more new members elsewhere after the move.

CDSS Leaves New York City

TK: So let’s talk about the move to Northampton [in 1987], and the early years there.

BF: One funny story about the move. Steve Howe wasn’t working in the office yet. He’d started working for me at camp part-time, and he had been doing stage management for the Theater for the Deaf and knew a lot about packing trucks from his tours with them. When it came time to move, we offered to help move the office staff who were going with us by putting their personal belongings in the same truck with the office gear. So we had this tour where we went to various people’s houses. Steve walked into the first one, looked at the pile of stuff, and said, “Two feet.” I didn’t know what that meant. Then we went to someone else’s house with more stuff, and Steve said, “Four feet,” and I still didn’t know what that meant. Then he looked at the office and he figured out the size of truck we needed. “Two feet” meant two feet of floor depth in the truck from floor to ceiling and wall-to-wall. And he was right! He knew how to estimate from his job as stage manager.

TK: So Steve was quite involved in the move, then, getting the truck?

BF: He was involved in the move; he didn’t join our year-round office staff until about a year after we moved up there. He was just summer help before that. Caroline Batson and Aithne Bialo-Padin moved with the office; they and I were the only ones who moved with the office to Northampton. Steve joined us a little later. Aithne stayed a couple of years, and then moved on to other things.

BF: Several years after the move we wrote new bylaws—Genny [Shimer] felt the Society needed a clearer structure—and we incorporated in Massachusetts, merged that organization with the New York corporation, and went through all sorts of legal this-and-that.

Around that time, we started [our programs at] Buffalo Gap. People down in West Virginia were saying. “There’s this great camp. Why don’t you come down here?” We did it partly because Pinewoods was so full. The English and American Week and the Family Week that started then still go on, because Timber Ridge is really the continuation of the Buffalo Gap programs. But just about when we started Buffalo Gap, we suddenly hit a downturn at Pinewoods. I remember when we started the Finance Committee meetings at your place, we had a couple of years of losing what seemed a lot of money in our terms.

TK: In my first meeting [as Treasurer ] there was a big blowup about our losing money and our need for financial controls. That’s why we created the Finance Committee.

BF: We did lose money for a couple of years and then we essentially regained everything we’d lost within a few years after that. It’s funny looking back at that, because we worked really hard at our finances, but it’s hard to say whether the improvement was due to our work or simply due to other factors bringing the campers back.

TK: Well, maybe the financial controls helped; they at least let us know what was going on.

Major Achievements at CDSS

TK: I wanted to get your sense of what you feel your major achievements have been, from moving the Society out of New York and making it more national. I think that clearly happened, to some extent.

BF: I agree; I think it happened as well. Later on, people had a different idea of what they wanted “national” to mean, but considering that I started with an organization that was focused on New York City and Pinewoods, I feel that we were very successful in becoming visible in a larger part of the country. A lot of what I did was to push support for groups—grants, liability insurance—to groups all over the country to help them grow. Encouraging the Family Week in California to get started, supporting it financially for several years to get it off the ground. Growing membership, becoming less ingrown. Those were the things I worked on. Also expanding camps. At its peak, we went from seven weeks at Pinewoods, when I started, to nine with the addition of two weeks at Buffalo Gap, plus three more at Ogontz, including a storytelling week. Then we went back to two at Ogontz, then one at Ogontz, and then [a combined] one at Timber Ridge. And now six at Pinewoods—that happened after my time.

TK: When you first started in Northampton you had a small staff, essentially no committees. So how did things change?

BF: In the move from New York, the old committees disbanded and only some were reformed immediately. The first committee that came up was Bylaws. The next was Finance, because we had the short term financial loss. Staff slowly grew. The office work grew. In New York we had one computer. Gene and Susan Murrow brought in the first CDSS computer, and we used that for a long time. It was a CPM Vector Graphics machine. Then, around the time we moved to Northampton, we migrated to a single DOS based PC. But it was just one computer. A board member from Michigan asked, “How can you get by with only one computer?” I hadn’t thought about it, we all just struggled to get computer time. But soon after we added one more, and one more….

TK: From the outside, it seemed like a slow, steady building. It’s interesting to me how organizations grow. In some ways it’s easy to grow, and it’s harder to shrink, or stop growing, because it feels like failure. But things can end up changing in ways that actually don’t work.

BF: There were times when I thought my role was to be a “brake.” Ideas would come through that were often good ideas, but their timing was wrong, or the speed at which people wanted to carry them out was wrong.

Berea Christmas Country Dance School

TK: I want you to talk about [the Christmas Country Dance School in] Berea [Kentucky] a little bit. You’ve been going there for a long time, and it’s an important part of your connection to the dance world. And it’s a different world.

BF: Yes, it’s a different world. So, Berea. In 1977 I got a ride across country with Stan Kramer22. My trip to Pinewoods that summer took me from California to Port Townsend, Washington for the first Festival of American Fiddle Tunes, then wandering back toward California and heading with Stan to Brasstown, North Carolina. Stan took me to the John C. Campbell Folk School and then up to Berea.

I got to Berea just in time to help tear down the Dodge Gym, which I never saw in operation. I don’t think I got back there again until I was Executive and Artistic Director. Berea had a tradition of having CDSS’s Director come on staff if he or she was a teacher. I think Jim had been there on staff, but the directors between Jim and me, who weren’t teachers, hadn’t. Genny had been teaching there, but she said that it was time for me to take over, and then she kept going anyway. In those early years, the ‘80s, I tended to do Berea for one or two years, then Brasstown’s Winter Week one or two years. Sometimes I’d do neither, so I wasn’t constant. Now things have changed—for the last ten years, or longer, I’ve been to Berea almost every year.

Berea reminds me of the [CDSS] dance weeks back in the ‘70s. It’s old home week: it’s a part of your family life and tradition to do it. Ogontz has turned into that for [my family] too; we go to CDSS’s Ogontz Family Week because it’s our family vacation.

TK: It’s interesting. CDSS has a lot of groups that are very different from each other. It’s not as if there’s a single model for anything. In a way, that makes it hard for the national organization to have a clear focus, because there are all these different groups doing all these very different things, and with very different needs.

BF: This is partly based on the stories I’ve heard about Gay (May Gadd), but I felt like she had an iron hand and made people do things the “right way,” her “right way.” There was an advantage to this in consistency, but its existence also meant it was harder for the groups that were different. When I came in as Director, one of my goals was not to have that iron fist. It wasn’t what the Society needed at that time; we needed to help all the different groups in their different ways, rather than to apply a single model.

Calling Career

TK: Let’s go back to your non-CDSS calling career. How did you get your gigs? Did you go out and seek them actively, or did people get your name through the grapevine?

BF: When I first started calling, I taught at community colleges, and I went looking for community groups that wanted dances. I also taught the class at U. C. Santa Cruz mentioned earlier. There weren’t many dance groups around hiring callers. I got involved in the international scene early on, and then, by the ‘80s, more dance groups existed, and I was able to start putting tours together. By the time I did my first tours of the Northwest, Penn Fix had moved back to Spokane, and had created this great newsletter in which he kept track of all the old-timey little dances up North. This gave me a list of contacts that I could use to set up a string of gigs. So I would put together a tour that would take me from Seattle to Spokane and out to Idaho and back again.

TK: You would write the organizers and say, “I’m going to be in the area. If you’re interested, I would love to put a tour together?”

BF: Yes. And I also started getting hired for weeks and weekends. Creating Mendocino English Week made me much more visible. First I started the Mendocino Camp and taught there. Soon thereafter, I got hired to teach at Family Week and English & American Week at Pinewoods. Just before I became CDSS Director I was asked to be Program Director for Family Week. Once I started with CDSS, I programmed about one week a summer, sometimes two. But programming was a big part of my job. When Buffalo Gap started, I was already scheduled to run a week at Pinewoods, and I also ran the first English & American Week at Buffalo Gap.

TK: One unusual aspect of your success with this career is your ability to handle both the artistic and the administrative sides of the job.

BF: Sometimes it was hard to juggle the two.

TK: And of course, doing Pinewoods was part of the job. That was Gay’s model.

BF: It was Jim’s model too. Back then the [NYC] office would shut down [during the summer]. Gloria Berchielli and some others would come by to pick up the mail, but no sales took place unless they were handled from Pinewoods. In my early days it was easy for me to leave my administrative tasks and go off on tour without having to think about CDSS while I was gone. Ten years later, CDSS work came with me on the tours.

TK: So, about your parallel career as a caller…

BF: Oh, yes. I feel like the things that brought CDSS to hire me were a mixture of my camp administration experience and my teaching ability. I’m not sure we all agreed on what I was supposed to do with that teaching ability. One board member said that being director would be a big boost for my teaching career. I thought that my teaching career was a big boost to CDSS.

TK: What about your English dance teaching? Presumably there was more of that when you became CDSS Director. And as you said, the number of groups grew, so that there were more groups wanting somebody to come in and teach.

BF: By the time I became CDSS Director I was a fairly accomplished English caller and contra caller, good enough to teach the advanced dance in NYC and to be on staff at CDSS adult dance weeks, but there were fewer places that would hire someone calling English. So I did more contra dance calling than English calling, but often did it with people who played English, like Laurie Andres and Cathy Whitesides. Of all the people I toured with, I toured with Laurie and Cathy more than with anybody else. Sometimes we’d be booked for an English dance and sometimes it would be a contra. As time went on, I got hired more for English. There had been an explosion of contra dance callers, and there weren’t nearly as many English callers available.

TK: That’s still true.

BF: Now I do primarily English country calling and the odd, rare, contra. It feels like the whole thing is just totally the opposite of what it was when I started. And when I call contras, it tends to be at community events with both English and contra.

TK: In the early years, did you ever consider that calling might be a way to make a living?

BF: Yes, I called for my living for a while in Santa Cruz. What that meant was that I lived really cheaply. I lived incredibly cheaply, and I earned very little from teaching. That’s when I had my international class and my English class on the UC campus and I taught at a community college and did the odd dance, but it’s hard to call that a living. By the time I was up in the Bay Area, I was teaching a lot all over the place. I would call at Berkeley and Stanford twice a month each, and I would do these private parties. I realized that I could have turned that into a livelihood, but it would have meant being on the road constantly. Even then I didn’t want to do that.

TK: When I started in the dance world, I did notice the big explosion in the ‘70s, and the increased number of people who were trying to make a living from both calling and music. I think the musicians were a bit more successful, perhaps, with that than the callers were. There were more venues for the musicians, and they could do concerts as well as dances.

You’re famous for your stories, and I’m wondering if you have some favorite ones you could tell. Does anything come to mind?

BF: We were talking about May Gadd. I had this image, possibly from something Ellen said, of this woman doodling while she taught, and ever since my impression of May Gadd has been “a rumpety tump, a rumpety tump.” Years later I was out canoeing with [my wife] Barbara [Russell] on Long Pond at Pinewoods, and we ran into some middle-school age kids. It turned out they were relatives of Steve Howe’s from across the pond. They asked where we were from and we replied Pinewoods Camp. Their reaction was, “Oh, you’re the “tiddely pommers!” [Both laugh.] The way camp is situated, C# [pavilion] is fairly well sound-isolated from the lake, but there’s a low spot that goes right through to the Point on the Conants’ property, heading right straight toward Ashanti [the Howe family cottage across the pond]. That’s what they’d hear at night, the “rumpety tumps,” but they called them “tiddely poms.”

TK: What about those early square dance days you were talking about?

BF: I learned squares—my western patterns called squares—from that fellow “John the bass player.” He’d call a full night of squares—the Virginia Reel plus four or five squares, a lot of polkas and a lot of gaps in between. People mostly bounced around and didn’t pay much attention to the caller. One of the first calling skills I developed was “patience.” It was the only way to survive that.

Then I went out and visited Duke Miller and fell in love with his sing-songy style of calling contras and singing squares, so I taped them and came home. But in my early days I couldn’t find any bands that would play the music for me. So I started doing just patter-call squares. Later on I shifted, so by the time I became Executive and Artistic Director I was pretty much doing New England squares and very little patter-call anymore. And I would do some singing contras too. Duke Miller sang Petronella and Money Musk and others.

I found out that Kate Barnes23 had also gone to the same dances I did, and had in her head the same Duke Miller sound, and we would set it up to do a duet. It was fun to do. I’d start at the microphone and would teach it and then sing it. A little while later I would still be there standing in front of the microphone, but Kate would start singing and people would think it was still me. Then suddenly we’d shift into harmony. Kate always did the harmony; I couldn’t sing harmony when I was also trying to call. The people were really confused. “Where did that second voice come from?” We did that for a while, especially with Money Musk.

The Present and Future

TK: Tell me what you are doing now.

BF: I’m still quite connected to CDSS—I was in the office just two days ago. In my new work as Executive Director of 1794 Meetinghouse, I organize summer concerts, and CDSS is helping sponsor three of our folk concerts amidst a whole summer of all kinds of music. I recently went to a Centennial fundraising party at Sukey and Rhett Krause’s house—it was really an Ogontz reunion. Because I like what CDSS is doing, and because I wanted to be a good role model, I publically got out my checkbook: I wanted people to know that we give too.

I also run a new dance program called New London Assembly. It’s somewhat ironic. For years CDSS has been putting on an Early Music Week, even though early music is not directly connected to CDSS’s mission. Meanwhile, Amherst Early Music Festival, which is an early music program, now is putting on an English Country Dance Week, even though English country isn’t directly connected to their mission. That’s in part because people on both boards, like Pat Petersen, suggested I lead an English program at their summer festival.

So I’m leading it now, and watching the dancers at New London reminds me of the old days. Back in the ‘70’s at the CDSS dance weeks at Pinewoods, I felt there was a culture of respectful learning, of coming to a dance and being quiet and listening to what the teacher had to say. And people had a fairly long attention span. As time has gone on, there’s been more chatter, less attention paid to the teacher, and it’s become harder to teach style. I realize I’ve contributed to that change, doing things like learning to teach quickly and trying to make English country dance more welcoming to newcomers, but that has also played into the modern culture of short attention spans. New London is different. When I started New London Assembly, it was outside the norm—it just wasn’t a place anyone normally went for English country. By chance, we attracted dancers who were all respectful listeners, and so we have been able to work on style in a way that is often hard to do at other camps. At New London, people come to learn. It’s not just recreation. So I go to New London, and it’s like a blast from the past, and I can teach differently there than I do elsewhere.

And that is my life now. I continue to run New London Assembly, to direct the 1794 Meetinghouse, and I’m doing nonprofit accounting locally for a number of small nonprofits. I also travel to teach, when I can, while also trying not to be gone too much from home—I love being home with my family. We still go to CDSS’s Ogontz Family Week whenever we can, and I’m often on staff. And the same is true with Berea’s Christmas Country Dance School. And we try to get to something at Pinewoods—I’ve been going there almost every summer for the last forty-four years, only missing two so far. All of this is a big part of my past, and a big part of my present and future too.

TK: Okay, this is good. I have my work cut out for me writing this out.

BF: Thank you, Tom.

CDSS thanks Tom Kruskal for interviewing Brad, Nancy Boyd for transcribing, and Sharon Green, Pat MacPherson and Caroline Batson for editing. Also thanks to Deborah Kruskal et al. for creating the Award party for Brad on October 24, 2015, in Athol, Massachusetts.

Footnotes

1 Mary Judson brought English country dancing to Los Angeles in 1967. Her group, The Carol Dancers, became the center for English country dance in Southern California, and fostered the growth of future dance leaders Brad Foster, Bruce Hamilton, Gene Murrow, and Lydee Scudder, among others.

2 Lydee Scudder began dancing at age five at Duke Miller’s Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire, square dance. In her Pasadena high school, she persuaded the administration to let her teach folk dance as an alternative to PE, and introduced folk dancing to her fellow student Brad Foster. Lydee, her sister Alice, and Brad danced with teacher Mary Judson and performed at Southern California’s Renaissance Faire.

3 Home to CDSS summer programs since 1933; near Plymouth, Massachusetts.

4 Longtime director of CDSS and before that of the NYC chapter of the English Folk Dance Society which became CDSS; May Gadd died in 1979.

5 See explanation later in the interview.

6 Duke Miller was a high school football coach from upstate New York who called summer dances in southern New Hampshire from the 1950s until the late 1970s. Well known for his singing calls, Miller influenced many callers, including Brad.

7 Marcel Vinokur (1929-2014) was an international folk dancing teacher for over sixty years. A pioneering aeronautical engineer, he contributed to the manned space program, working at NASA Ames Research Center.

8 National Director of CDSS from 1975-1977 and Artistic Director for three years after that, Jim Morrison is a musician, caller, and display dancer. In 2014 he received CDSS’s Lifetime Contribution Award; he lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.

9 Choreographer, composer, musician, singer, and caller, Patrick Shuldham-Shaw (1917-1977) started English folk dancing in London at the age of six. In 1971 he was awarded the English Folk Dance and Song Society’s highest honor, its Gold Badge.

10 Founded in 1948, Stockton Folk Dance Camp is located at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, and specializes in international folk music and dance.

11 Sidney “Nibs” Matthews (1920-2006) was a morris dancer, caller, and director of the English Folk Dance and Song Society.

12 Bob Parker (1929-2012) was a member of London Folk and a teacher of English traditional dance at the Royal Ballet School at White Lodge.

13 Charles “Chuck” Ward, organist and pianist; in the 1970s, he, Tom Kruskal, and Brad Foster laid the foundations for the Bay Area Country Dance Society. Chuck is a 2009 CDSS Lifetime Contribution Award recipient.

14 Lea Brilmayer is the Howard M. Holtzmann Professor of International Law at Yale Law School. While a student at U. C. Berkeley, she frequently played for English country dances.

15 An international folk dance café in Berkeley.

16 Bruce Hamilton is an internationally known English and Scottish country dance teacher. A former president of the CDSS Governing Board, he is programmer of BACDS’s Peninsula English country dance.

17 In the 1970s and ‘80s, there were two levels of group membership in CDSS: Centers, for the larger and more formally organized groups, and Affiliates for the smaller groups. It caused some confusion and the designation was later simplified to the single “Group Affiliate.”

18 Longtime and much loved English country dance teacher who taught in NYC and at workshops and programs around the country; she died in 1990.

19 Jeff Warner was President, Genny Shimer was Vice President, and David Chandler was Secretary; the four officers had comprised the Search Committee for the position of Director. Brad was officially hired after the January 1983 Exec meeting; he was in his second CDSS National Council term, and had programed CDSS’s Family Week the previous summer. His goals for CDSS, stated in his application for the job, were: “increased outreach to and communication with center/associates and members, as well as greater exposure among non-CDSS groups; increasing the membership of the Society by developing new ways to show its value and effectiveness for members; and quality programs at reasonable costs to participants as well as to the Society.” (Source: minutes of the CDSS Executive Committee meeting, January 17, 1983)

20 Now called Country Dance*New York (CDNY)

21 Now called Folk Music Society of New York, a.k.a. New York Pinewoods Folk Music Club

22 An original member of the Bay Area’s Claremont Country Dance Band (which worked closely with Brad Foster in the late 1970s), Stanley Kramer still plays violin with the Nonesuch Country Dance Players, Bangers and Mash, and other bands.

23 Contra and English country dance musician Kate Barnes currently plays in the Latter Day Lizards, Bare Necessities, Big Bandemonium, Dark Carnival and Yankee Ingenuity; she also teaches, records, publishes music books, composes and crafts wooden whistles. She lives in Massachusetts.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Isaac Banner

Isaac Banner Seth Tepfer

Seth Tepfer Christa Torrens

Christa Torrens Ellie Shogren

Ellie Shogren Sharon Green

Sharon Green Dilip Sequeira

Dilip Sequeira