Skip to content

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

- Hive Mind—Collaborations

- Nontraditional Funding and Focused Mentorship: How We’re Growing a New (Awesome) Contra Dance Community in Portland, ME, by Dela Taylor

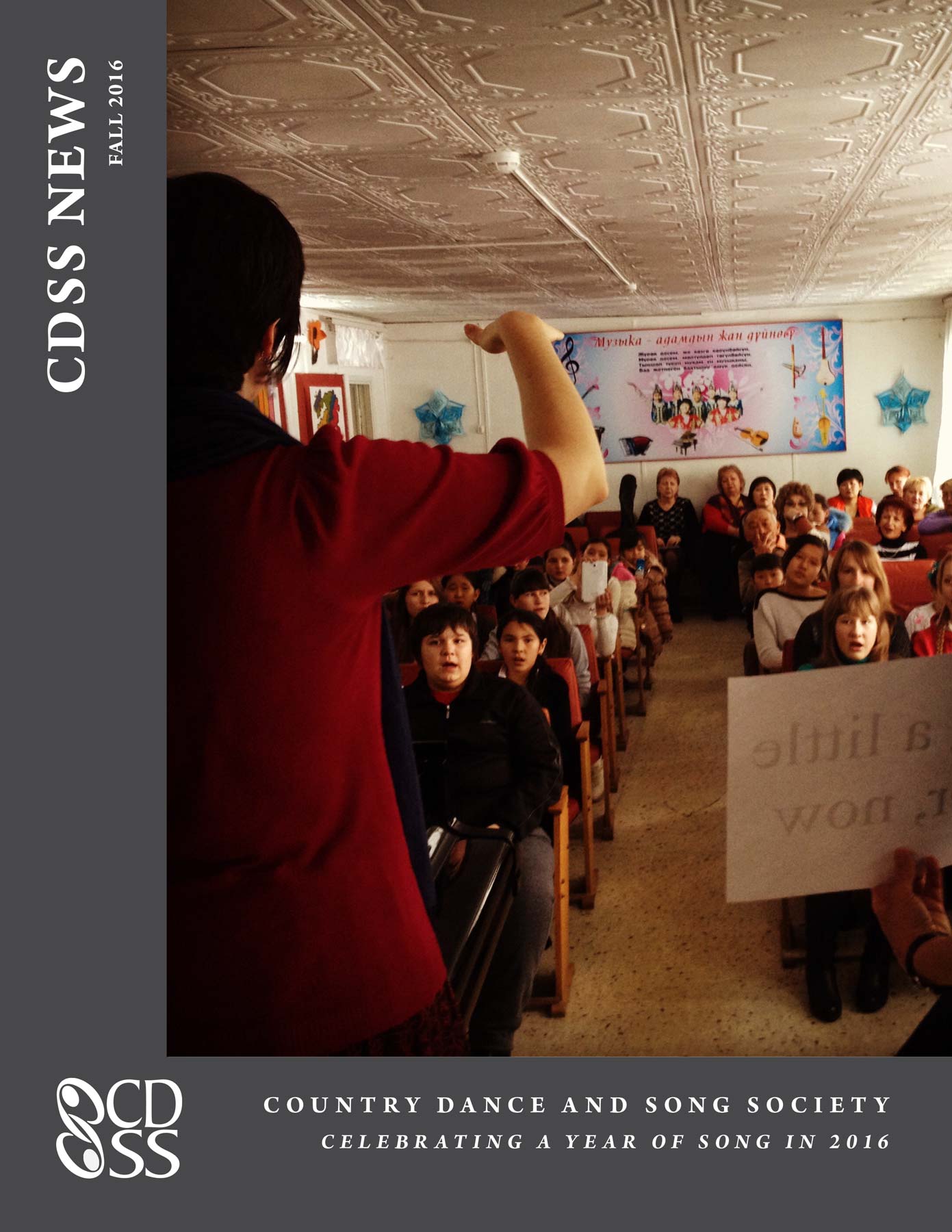

- Windborne on American Music Abroad, by Jeremy Carter-Gordon

- The Dance in North Sycamore, a poem, by Dudley Laufman

- English Country Dancing in Gainesville, FL, by Pete Turner

- Continuing Education for Callers, by Michael Kernan

- CDSS Sings—Bold Lovell, by John Roberts

- What Dancing Taught Me, by Laurel Owen

- Yoga for Dancers: Float the Floating Ribs and an Altar for the Heart, by Anna Rain

- American Traditional Song Symposium

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

- Brad Foster―A Calling Career (excerpt), interviewed by Tom Kruskal

- News from Canada―Chehalis Contra Dance Weekend, by Sally Sheedy and Jane Srivastava

- Proactive Management of “Problem Dancers”―Creating a Dance Environment Safe for All, by Will Loving

- What’s Your Pronoun?, by Miriam Newman

- What I Did Last Summer―A 24-Year Old’s First Time at Sleep-Away Camp!, by Alexandra Deis-Lauby

- Yoga for Dancers―Yes, Virginia, More Hip Openers…, by Anna Rain

- The Ballet and the Country Dance, by May Gadd (from The Country Dancer, December 1942)

- The Centennial (tune), by Jonathan Jensen

- The Centennial (dance), by Philippe Callens

- CDSS Sings—In Accents Clear?, by Deborah Robins and Larry Hanks

- Thank You for 2015, and Happy 2016!

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

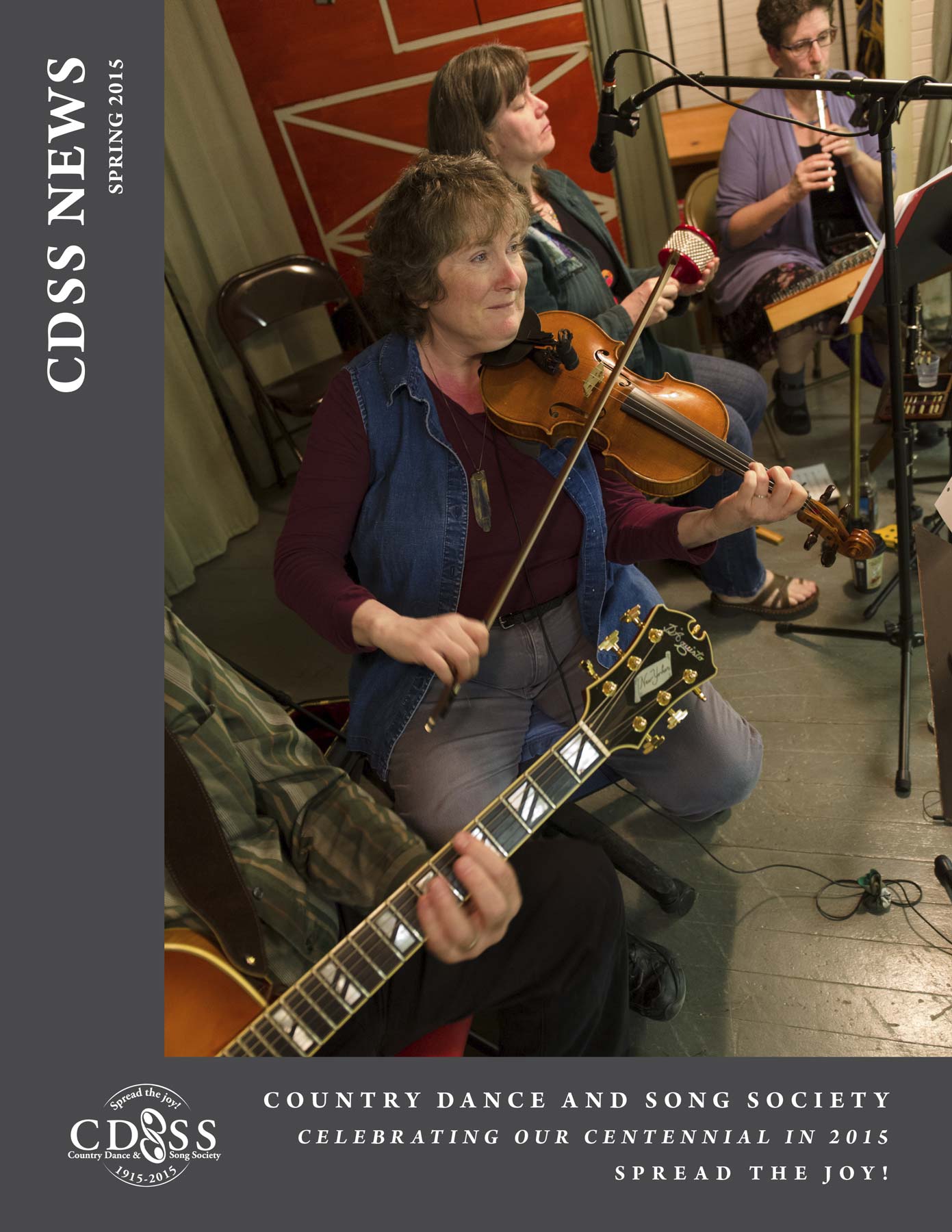

- Sing Loudly for CDSS’s Year of Song, by Rima Dael

- Teaching the Country Dance, by May Gadd, CDSS National Director, 1937-1972

- Talking Square, by Rima Dael

- “I Call Square Dances for the Army, Do You?”, by Lovaine Lewis (from The Country Dancer, July 1942)

- News from Canada―From the Dining Room to a Summer Assembly, by Maxine Louie

- Book Review: Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics, reviewed by Tony Parkes

- Book Review: Appalachian Dance, reviewed by Susan English

- Yoga for Dancers―Abdominal Integrity, Part the Second, by Anna Rain

- CDSS Sings—“Jenny Jenkins”, by Kim Wallach

- Waves of Grains, a dance, by Bob Green

- Dance and Music in Literature: “A Ball in the Mines,” from Three Years in California, by J.D. Borthwick

- Who You Gonna Call?, by the CDSS Staff

- About Our Centennial

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

- Centennial Tour 2015―Morgantown, WV, by Morgantown FOOTMAD; photos by Milly Mullins

- Centennial Tour 2015―Lawrence, KS, by Lauralyn Bodle

- News from Canada―An Imposter at Puttin’ On the Dance 2, by Siri Paulson

- Yoga for Dancers―Abdominal Integrity, Part the First, by Anna Rain

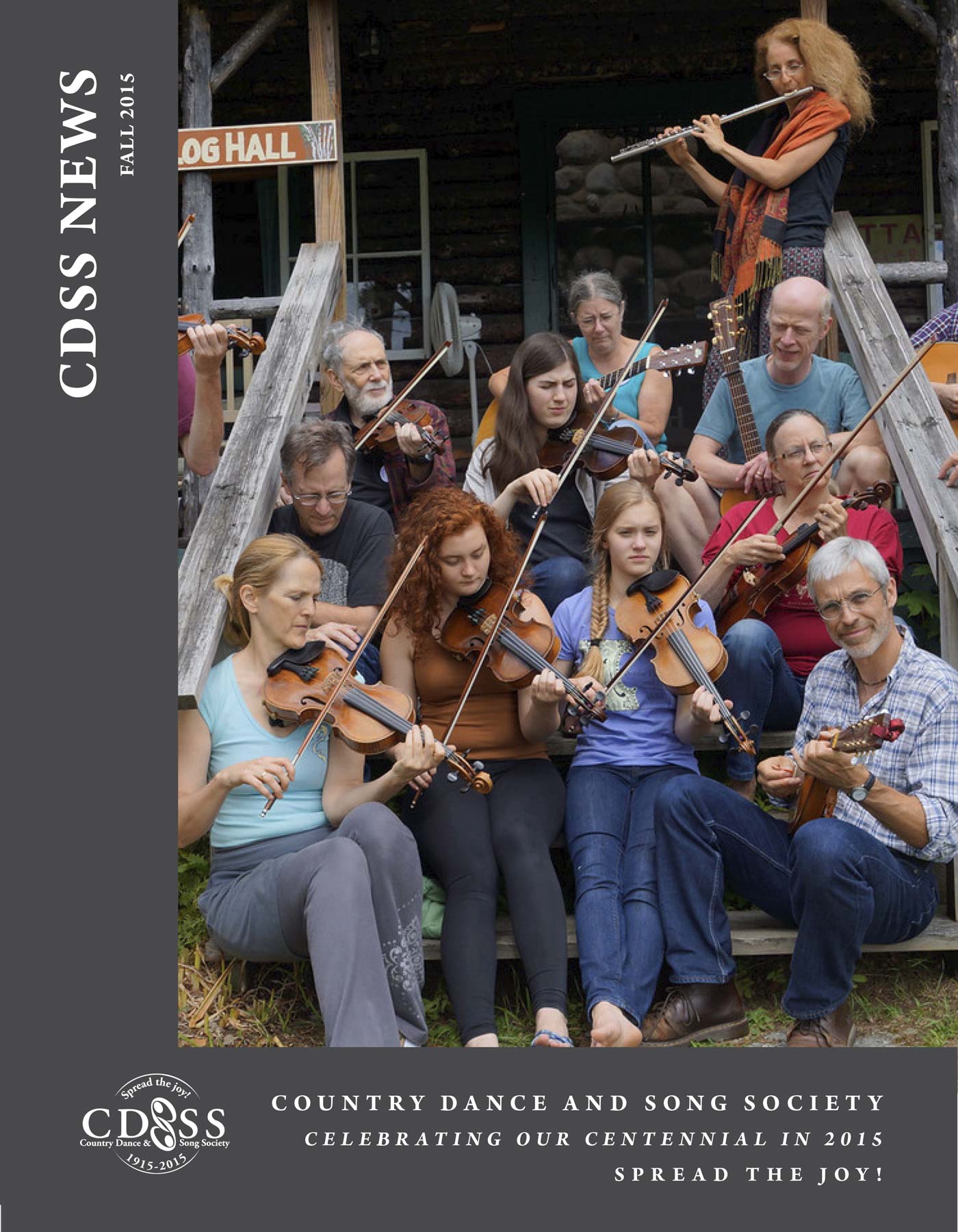

- Dance Musicians’ Resources, by Max Newman, Jill Allen and Susie Lorand

- “People support what they helped create”, by Susan Peterson

- 2015 Posthumous Award―Warren Argo

- CDSS Sings—“Jack Went A-Sailing”, by Jeff Davis

- Centennial Reel, a dance, by Rick Mohr

- Double Jubilee, a dance and tune, by Dave Wiesler and Gary Roodman

- Spread the Joy, a song, by Jonathan Jensen

- About Our Centennial

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

- 15 Things You Can Do to Celebrate the CDSS Centennial

- Centennial Tour 2015―Coos Bay, Oregon, by South Coast Folk Society

- Yoga for Dancers—Love Your Hips and They’ll Love You Back, by Anna Rain

- Ten Reasons Not to Book, by Eric Engles

- Local Dance Finds Fundraising Solution, by Flora Chamlin

- Sturtevant—A Hike-in Dance Camp, by Carol Ormand

- CDSS’s Traveling Exec Samples Kentucky Dance and Song in Louisville, by Jenny Beer

- Group Corner—Do You Know How-to…?, by Jeff Martell

- Share the Joy…CDSS’s Summer Camps 2015

- CDSS Sings—Traditional Song in Maine (with song “The Lumberman’s Alphabet” by Larry Gorman), by Pam Weeks

- Four Have Sprung, a dance, by Yoyo Zhou

- Two Poems—“Dance Floor” by Kelly Perkins and “Fiddle Camps” by Dudley Laufman

- About Our Centennial

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

- Director’s Report—Arts Exist to Serve Communities, by Rima Dael

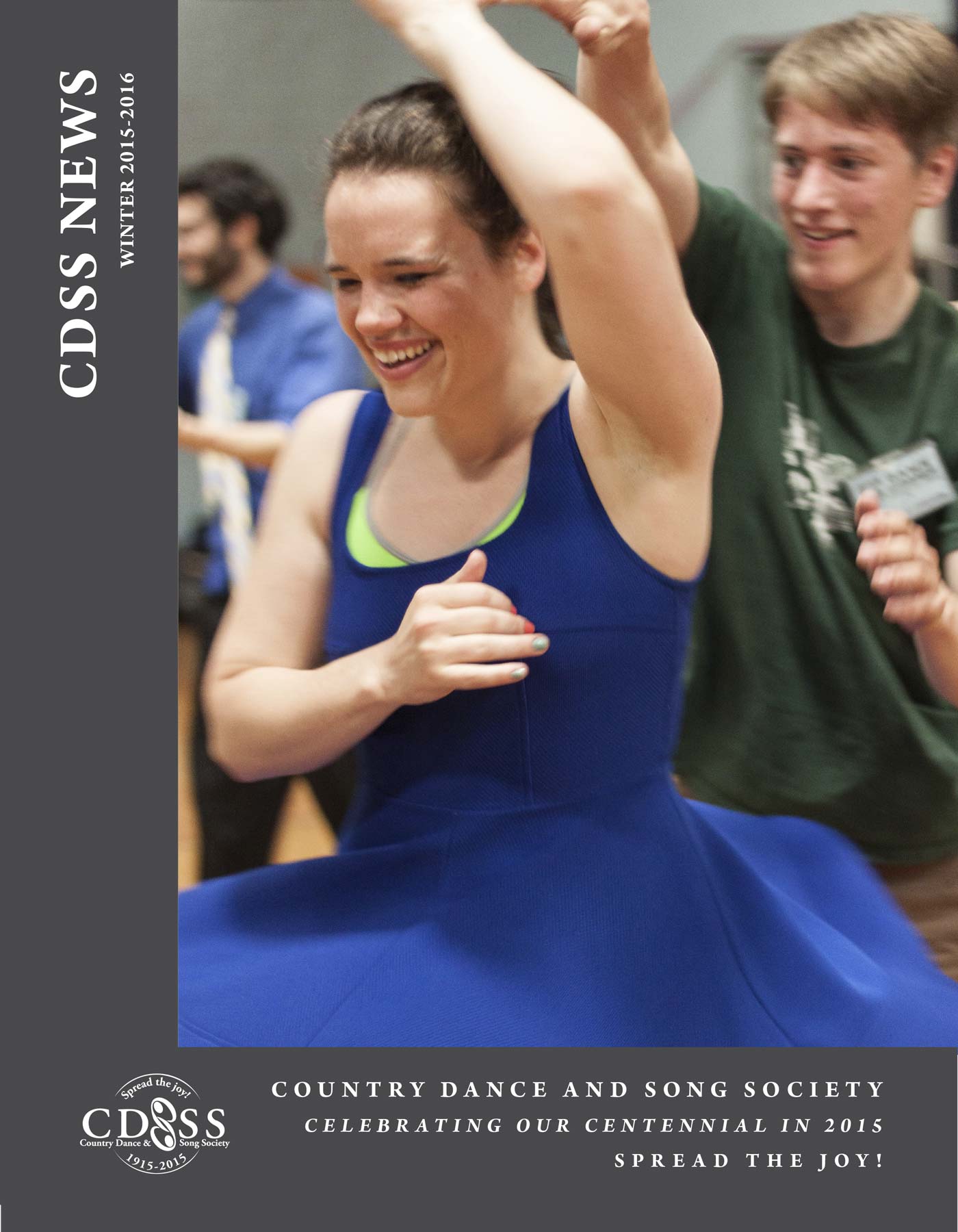

- Celebrate the Joy―Centennial Updates

- Centennial Tour 2015―Halifax, Nova Scotia, by Dottie Welch and Nils Fredland

- Farewell, I Must Be Gone—a Reflection, by Emma Breslow

- Community Dance Works Wonders for Veterans with PTSD and Brain Injuries, by Deborah Denenfeld and Jean Borger

- Ferry Boat Contra Dance, by David Means

- Contra Dancing Comes to Paris, by John Sweeney

- CDSS Sings—Sacred Harp and Community, by Sharon McKinley

- Box the Ocean, a dance (with tunes: “The Humpty Dumpty” and “Mackoronie Reel” by Leo Maring), by Madame Padovan’s School of Dance, a.k.a. 10-12 year olds’ class at CDSS Week at Timber Ridge

- Yoga for Dancers—Keep Practicing: Release Attachment to Immediate Results, by Anna Rain

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

- 2015 Camps―A Letter from the CDSS Board President, by David Millstone

- Celebrate the Joy―Centennial Updates

- Centennial Tour 2015―Fiddlefern Country Dancers in Owen Sound, Ontario, by Nils Fredland

- Group Corner―Talent Buying and Touring Acts, by Jeff Martell

- What We Believe―Building Family, by Rima Dael

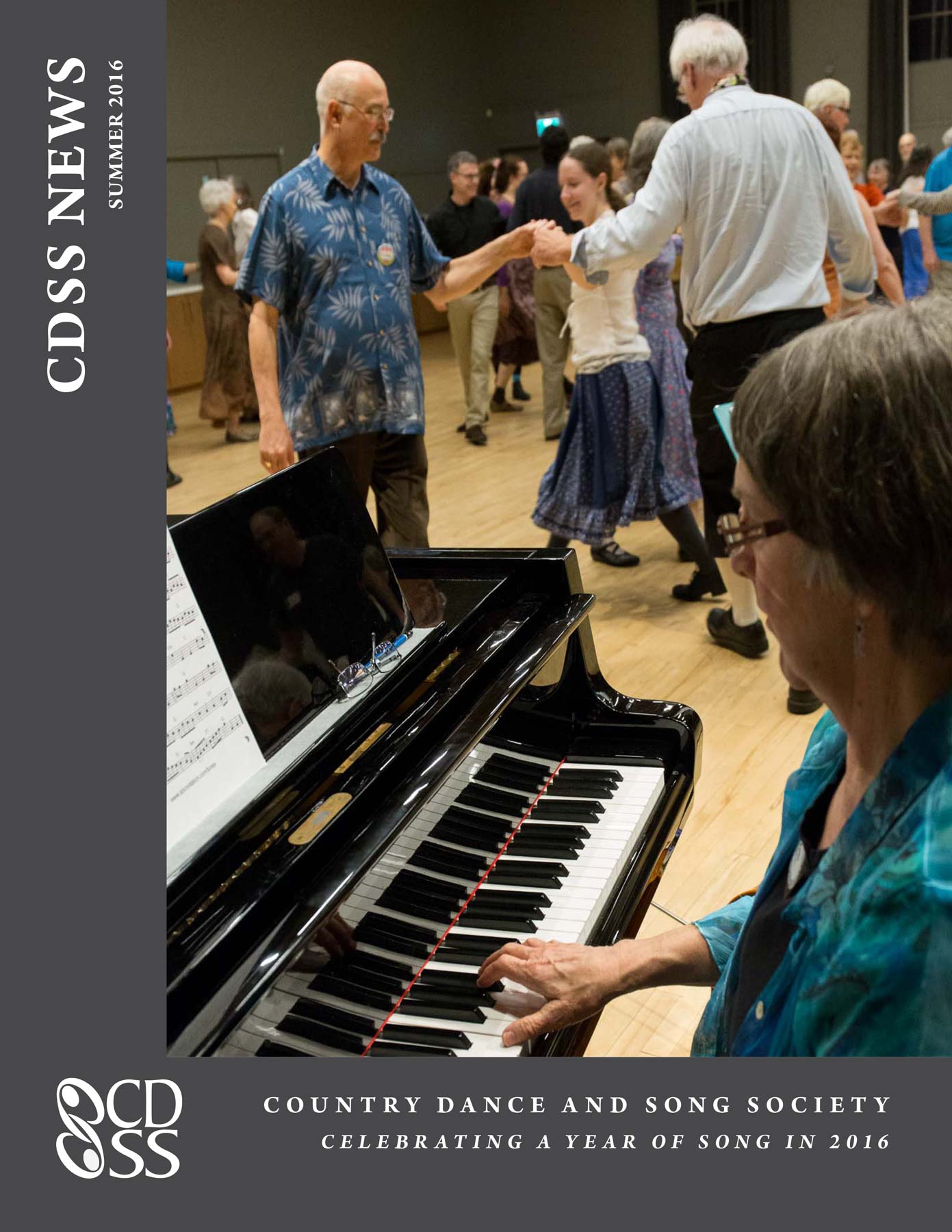

- How to Photograph a Contra Dance, by Doug Plummer

- Yoga for Dancers—Open the Shoulders, Open the Breath, by Anna Rain

- ContraResolution―A Free Dance for Beginners, by Loren Shlaes

- Mentors—Allan Block, by Jim Morrison

- Heavenly Bodies, a dance, by Al Green

- CDSS Sings―“And When I Rise”, by Bob Walser

Table of Contents PDF

In This Issue

- Balance and Sing (Store Update)

- Letters and Announcements

- Group Corner―Sound Engineers, by Jeff Martell

- CDSS Centennial Tour 2015―Tucson, Arizona, by Donna Fulton and Nils Fredland

- News from Canada―Ooh La La, a Contra Dance Weekend Built on Cultural Exchange and Local Abundance, by Jaige Trudel and Adam Broome

- A Golden Anniversary—Fifty Years of the Pinewoods Morris Men, by Natty Smith

- Yoga for Dancers—Why the Well-Lifted Spine? For Breath’s Sake!, by Anna Rain

- Highland Farewell, a dance (with tune “Highlander’s Farewell”), by Pat Petersen

- Shenandoah Harmony—Singing Old Songs from a New Book (with song “Consolation New”), by Rachel Wells Hall

- CDSS Sings―Hangman, Hangman, Slacken Up Your Line, by Hannah Shira Naiman

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.