Derek Piotr presents “We’re All Jolly Fellows that Follow the Plough,” a rare tale of hard work well rewarded.

Derek Piotr presents “We’re All Jolly Fellows that Follow the Plough,” a rare tale of hard work well rewarded.

The CDSS Educators Task Group presents a new set of Lesson Plans to introduce students to a variety of topics in traditional music and dance. Check out the sample plans, and contribute your own at [email protected].

In episode 12 of From the Mic, Wendy Graham tells Mary, “My only job is to help people have fun. Fun, F-U-N, three letter word. That’s it!” Wendy’s passion for music, song and dance caught fire in 1991 on a Danish-American Exchange (DAE) youth dance tour to Denmark. Today, Wendy leads English and American community folk dances and teaches social couples dance across the country and around the world.

Denise and Stuart Savage present “Reynardine,” an English ballad in which a young woman is led astray by a stranger who may or may not be a tricky fox.

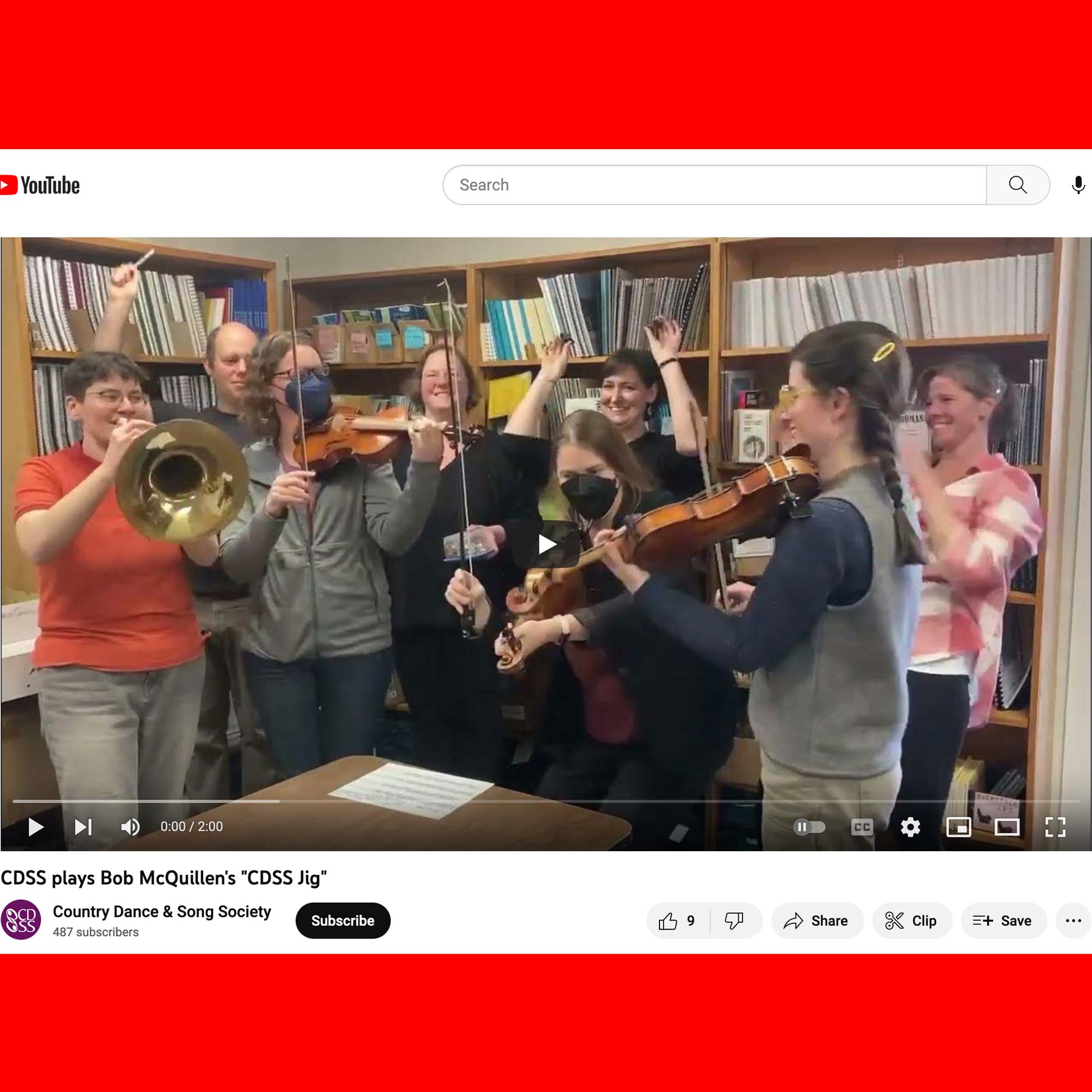

“CDSS Jig” by Bob McQuillen, played by some of the CDSS staff to celebrate moving to our new office and Mac’s centenary this year.

Have you heard about the project to play all of Bob McQuillen’s (nearly 2000!) tunes this year? Learn more in the latest issue of the CDSS News or at mcquillentunes.com.

The Spring 2023 CDSS News is now available! Meet this year’s Lifetime Contribution Award winners; hear how Jacob Chen passes on traditions to the next generation with Folk Song Fridays; learn how a dance camp in Washington state kept Covid in check; celebrate Bob McQuillen’s centennial at KwackFest; and much more.

Hello from our new office, just down the hall from the old one! If you’d like to visit the CDSS store in person, check out the new directions for finding us in the building.

How lucky we are to have Laurel Swift as a co-Program Director at CDSS Family Week at Agassiz Village this summer! Laurel is leading classes on tin whistle and clog dance and a special performance class just for teens, and she was just featured in this article from Tradfolk. Find out more and register for camp.

The slideshow, video, resources, and transcript from our March 2023 Web Chat are now available. Executive Director Katy German hosted this discussion about volunteer management and addressed key volunteer-related questions.

Sue Burgess introduces “Free and Easy to Ramble Along.” Sue writes: “A man goes on his rambles in Ireland and Scotland, having a good time meeting women, and perhaps breaking a few hearts along the way. In 2007, I was interested to hear well-known singer Peta Webb sing a version where the genders are reversed and the story told from a woman’s point of view.”