Submitted by Sally Rogers

I learned this version of the great ballad “Matty Groves” (Child #81, also called “Little Musgrave”) from the singing of banjo player/folklorist/artist Art Rosenbaum in the mid 1970’s, when we visited East Lansing and performed at the Ten Pound Fiddle Coffeehouse. We had a singing party at Stan Werbin and Sharon McInturff’s home after the concert, where I heard him sing this song.

I love that Robert Ford, who killed Jesse James, found his way into this American version of the ballad.

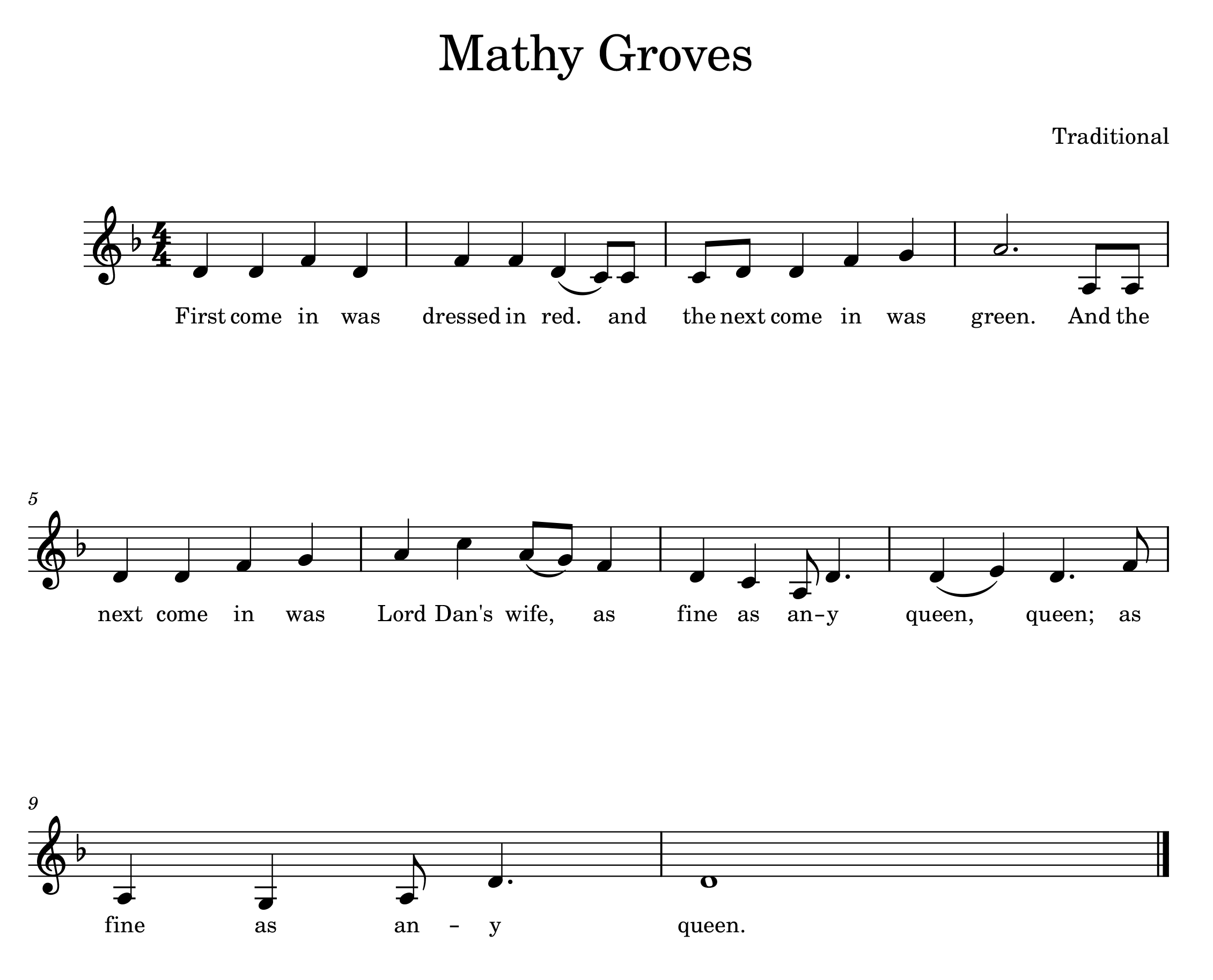

Listen to Sally’s recording of “Mathey Groves:”

Lyrics: Mathey Groves

Traditional, learned from Art Rosenbaum, from Dillard Chandler

First come in was dressed in red and the next come in was red

The next come in was Lord Dan’s wife, as fine as any queen, queen

As fine as any queen

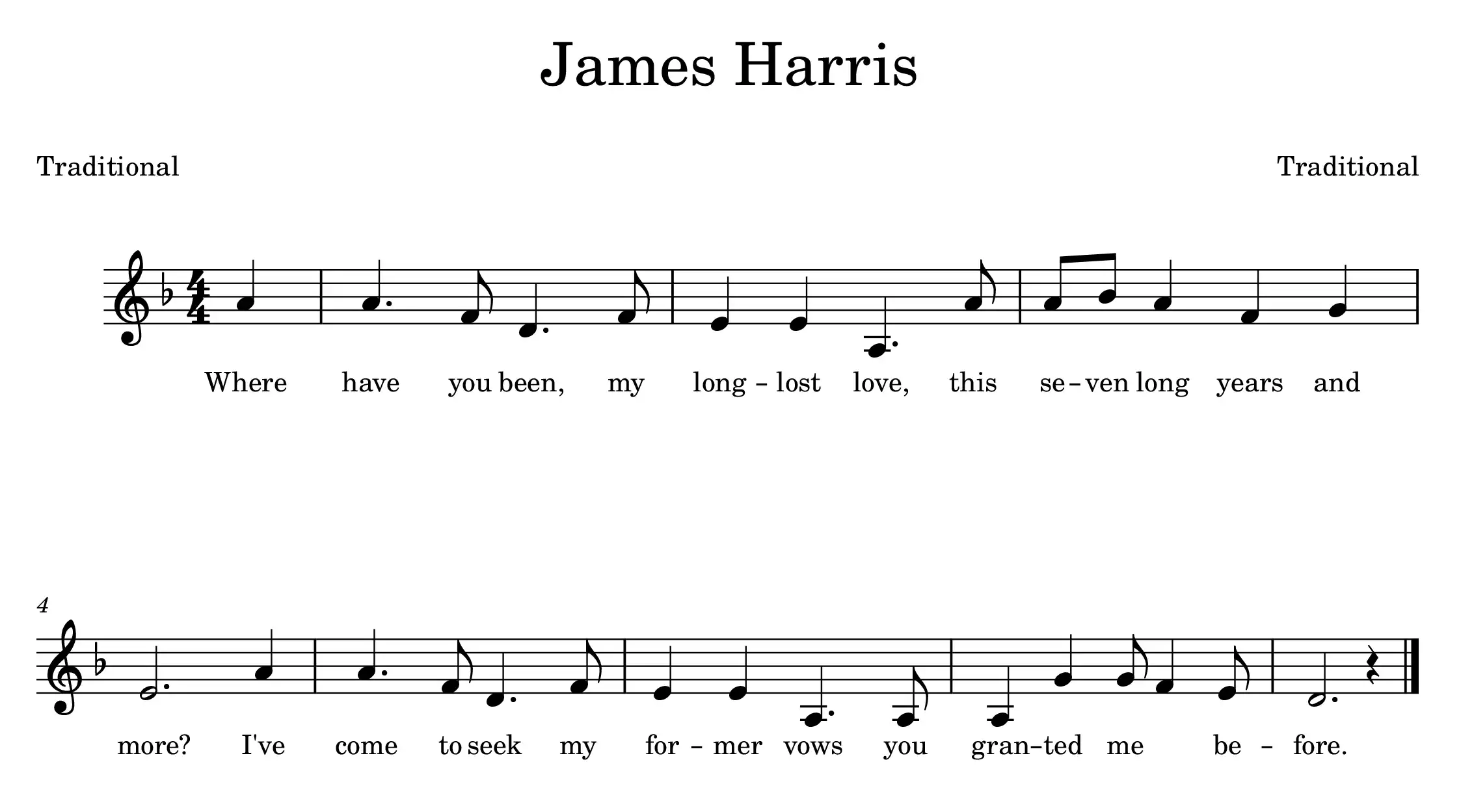

Well, she stepped up to little Mathey Groves, “Come home with me tonight”

“I can tell very well by the ring that you wear that you are Lord Dan’el’s wife, wife

You are Lord Dan’el’s wife”

“It makes no difference whose wife I am to you or other men.

For my husband he is far away, he’s in some distant land, land”

Well, little Robert Ford was standing by, heard every word was said.

“If I should die before daylight, Lord Dan’el shall hear this news, news”

So he run til he come to the broken-down bridge, and he turned on his breast and he swum.

He swum til he come to the green river shore and he turned on his feet and he run, run.

He run til he come to Lord Dan’s castle, then he pulled on the bell and rung, rung.

“What news, what news, oh Little Robert Ford, what news have ye brung?”

“It’s little Mathey Groves in bed with your wife. Gonna be some hugging done, done.”

“If this be a lie, if this be a lie, you’re a-tellin’ on to me

I’ll build the tallest scaffold in all Scotland, and hanged you shall be, be.

“If this be a lie, if this be a lie, I’m a tellin’ unto thee.

No need to build no tall scaffold, you can hang me from a tree, tree”

So he gathered up a few good men and he started off with a free good will.

He took his bugle from his side and he blowed it both loud and shrill, shrill

Well, little Mathey Groves was lying in bed. “It’s time for me to go.

For there’s your husband a comin, I can hear his bugle blow, blow”

“Lie down, lie down, oh Little Mathey Groves

Lie down and go to sleep.

It’s nothing more than my father’s shepherd a-callin’ for his sheep, sheep.”

Well, they fell off to a hugging and a kissing and they fell off to sleep.

The very next morning when they awoke, Lord Dan’el’s at their bed feet, feet.

“Oh, how do you like my clean white pillows and how do you like my sheets?

And how do you like my own little wife who lies in your arms asleep, sleep?”

“It’s well do I like your clean white pillows and well do I like your sheets

But best of all is your own little wife who lies in my arms asleep, sleep.”

“Get up, get up oh, Little Mathey Groves.

Put on, put on your clothes

For I never want it to be said a naked man I slew, slew”

“Oh, give me a chance, oh, give me a chance, a chance for my life

For there you stand with two glitterin’ swords and me not as much as a knife, knife”

“I’ll give to you the best I have and I shall take the worst

And you shall strike the very first lick and strike it like a man

And I shall strike the very next lick and I’ll kill you if I can, can”

Well, little Mathey Groves struck the very first lick and he struck an awful blow

And Lord Dan struck the very next lick, and laid him on the floor, floor

He took his little woman by the hand and he put her on his knee

Saying “Which of them do you like the best, little Mathey Groves or me, me?”

“It’s well do I like your red rosy cheeks and well do I like your chin

But I wouldn’t trade little Mathey Groves for you and all your kin, kin”

So he took his little woman by the hand and he led her through the hall.

He put a special agin her head, let her have a special, ball, ball.

Sally Rogers writes: I’m a lover of traditional and contemporary folk music and have been performing for nearly 50 years.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Isaac Banner

Isaac Banner Seth Tepfer

Seth Tepfer Christa Torrens

Christa Torrens Ellie Shogren

Ellie Shogren Sharon Green

Sharon Green Dilip Sequeira

Dilip Sequeira