Introduced by Kim Wallach

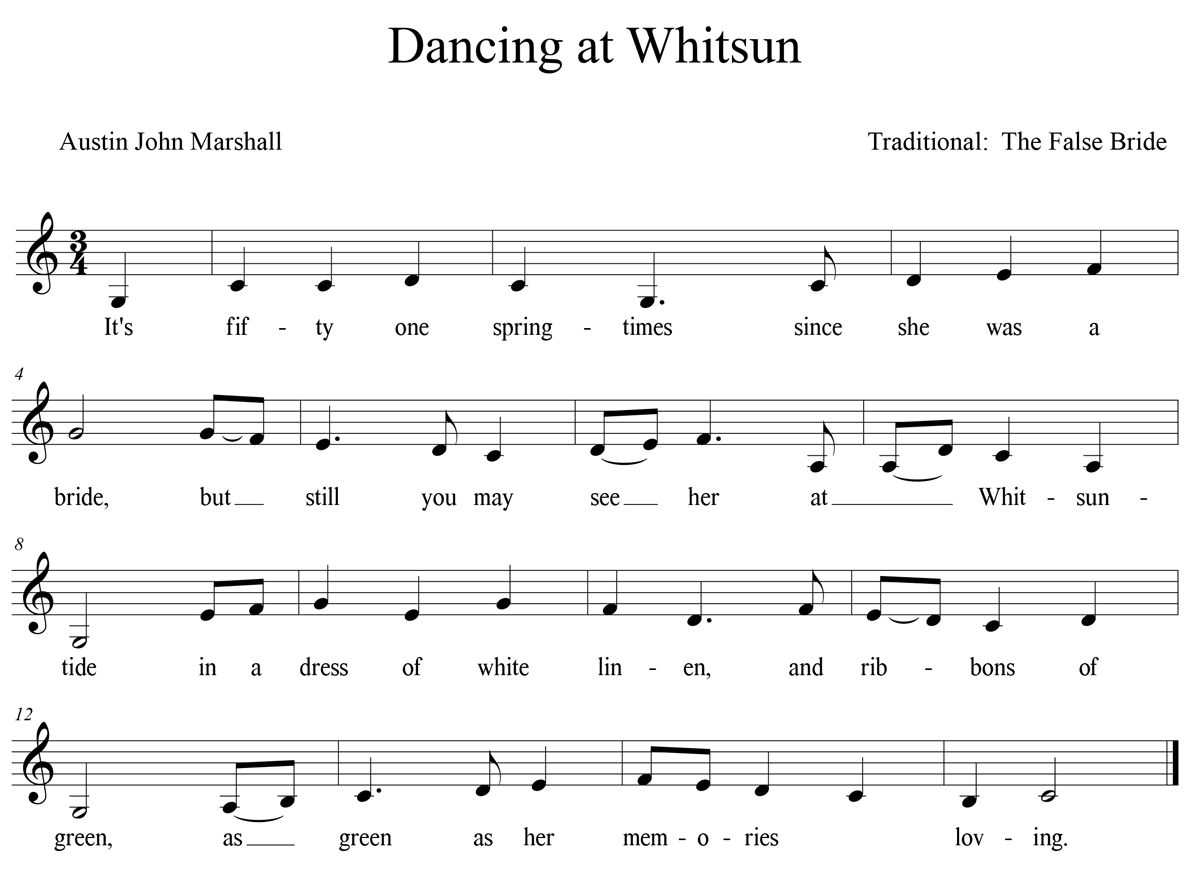

We dance in the month of May with Morris and Maypole, so it is fitting that the song of the month be about Morris dancing. Dancing at Whitsun, written by Austin John Marshall to the tune of “The Week Before Easter” or “the False Bride” was first published in 1968 in Karl Dallas’ book, The Cruel Wars, and first recorded by Shirley Collins in 1969 as part of the Anthems in Eden Suite.

Whitsun is the seventh Sunday after Easter, and is short for “White Sunday.” It marked the beginning of a week’s holiday for medieval villeins (feudal tenants) from service on the lord’s demesne. This made it a good occasion for celebration, including fairs, Morris dancing, parades, with choirs and brass bands, and girls dressed all in white.

Morris dancing was exclusively a male domain for several hundred years, until the First World War decimated the young men of England. In some villages, there were no young man at all to carry on the tradition, and it would have died if not for the women who danced in memory and honor of their lost fathers, brothers, sweethearts and sons.

I love this song, with an ancient melody and modern words that evoke the terrible loss of the war not with descriptions of gore, but by painting the landscape of their absence. The women cope with their loss by preserving what they have left – the tradition of dance that would also die without the men.

This song has also been recorded by Maddy Prior and Tim Hart, Priscilla Herdman, Jean Redpath, and Bok, Trickett and Muir. Austin John Marshall and Shirley Collins (his wife at the time) ended the song with this verse from the Staines Morris to infuse some hope into the mournful song:

Come you young men come along

With your music, dance and song

Bring your lasses in your hand

For ’tis that which love commands

Then to the Maypole haste away

For ’tis now a holiday

The Tim Hart and Maddy Prior version is offered here.

Lyrics

It’s fifty-one springtimes since she was a bride,

But still you may see her at each Whitsuntide

In a dress of white linen and ribbons of green,

As green as her memories of loving.

The feet that were nimble tread carefully now,

As gentle a measure as age do allow,

Through groves of white blossom, by fields of young corn,

Where once she was pledged to her true love.

The fields they are empty, the hedges grow free,

No young men to tend them, or pastures go see.

They’ve gone where the forests of oak trees before

Had gone to be wasted in battle.

Down from their green farmlands and from their loved ones

Marched husbands and brothers and fathers and sons.

There’s a fine roll of honour where the Maypole once was,

And the ladies go dancing at Whitsun.

There’s a row of straight houses in these latter days

Are covering the Downs where the sheep used to graze.

There’s a field of red poppies, a wreath from the Queen.

But the ladies remember at Whitsun,

And the ladies go dancing at Whitsun.

(Thanks to Wikipedia, and a lengthy thread on Mudcat, for much of the information.―KW)

Kim Wallach is an elementary music teacher, songwriter, singer, morris dancer, Children’s Music Network board member, and mom, currently cohabitating with a Westie in Keene, NH. Her article about the children’s song “Jenny Jenkins” appeared in the CDSS Sings column in the CDSS News, Fall 2015.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.