Submitted by Margaret Walters

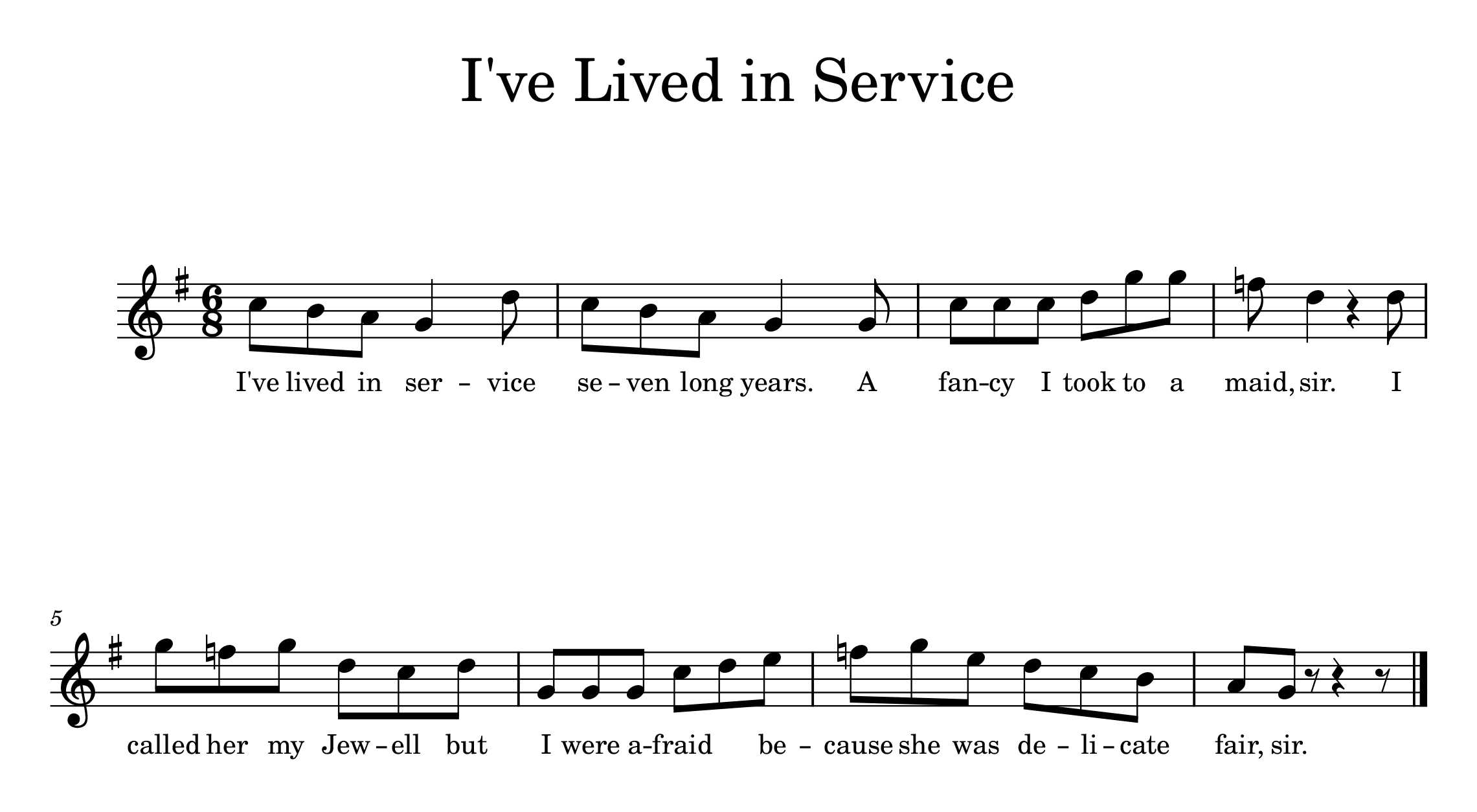

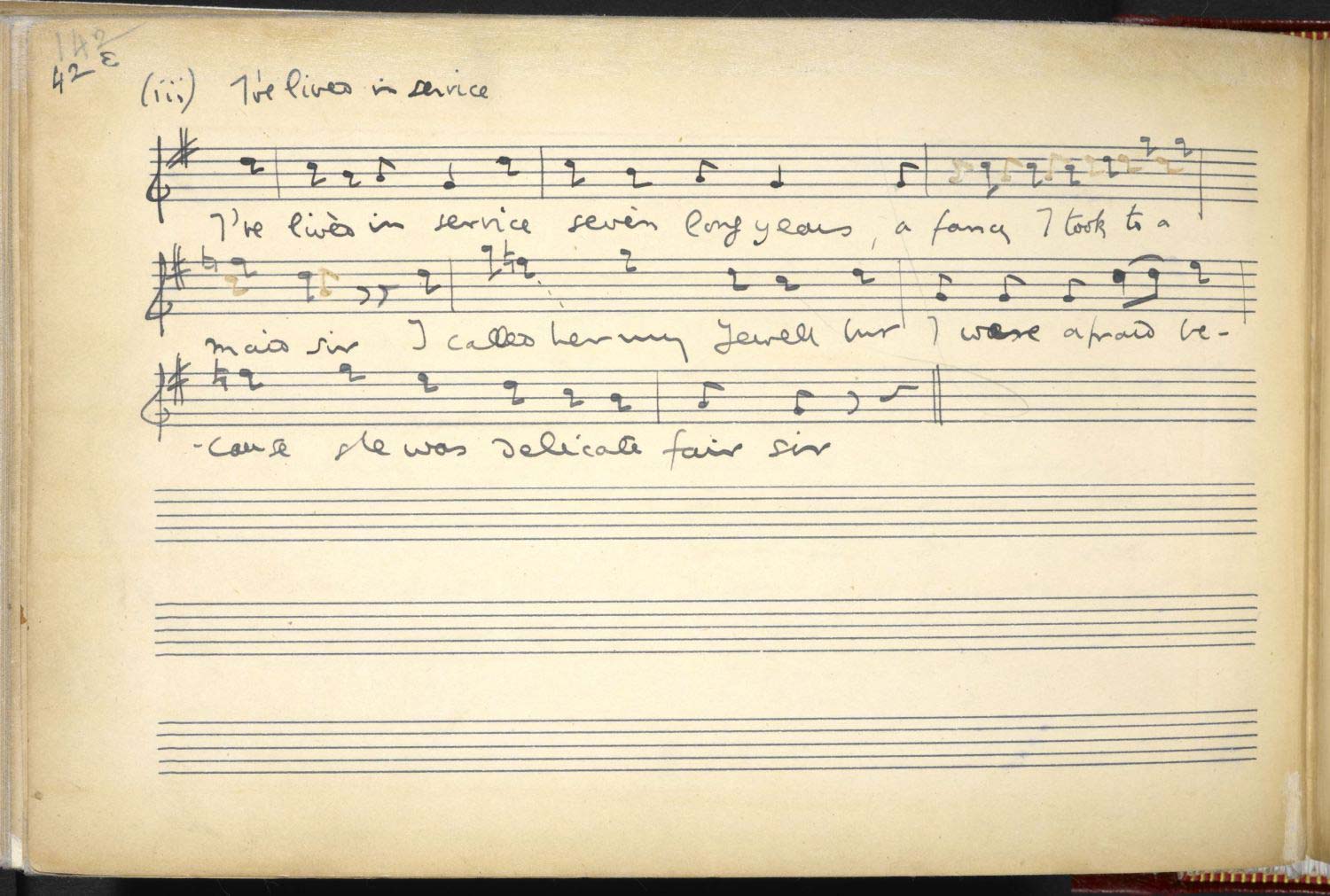

“I’ve Lived In Service” was collected in 1904 from Mrs Harriett Verrall of Monxgate near Horsham, Sussex by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

I learned it around 1980 from the singing of Vic Gammon, who recorded it with the Pump and Pluck Band on a cassette called “What a Beau My Granny Was.”

Vic wrote: “Yes, that is an interesting song, and pretty unique—I have never seen another version of it. (Roud number 1483.) Yet it speaks to a very real situation in pre- and early-industrial England, where youngsters would go into domestic service and apprenticeships in their early teenage years.”

Listen to Vic singing “I’ve Lived In Service:”

Listen to Margaret singing her version:

Lyrics

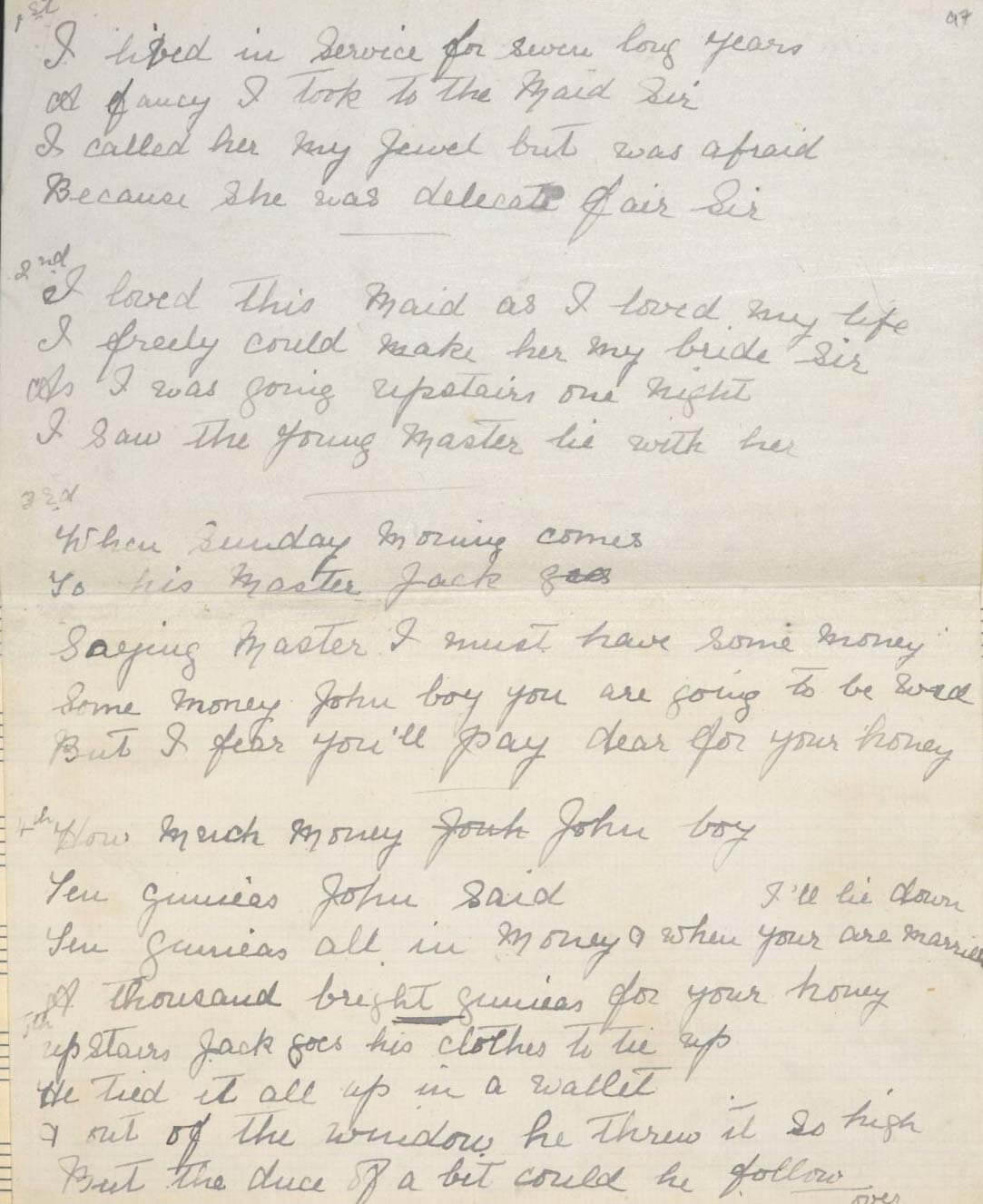

I’ve lived in service seven long years

And it’s fancy I took to a maid, sir

I called her my jewel but I was afraid

Because she was delicate fair, sir

I loved this maid as I loved my life

And it’s fair I would make her my bride, sir

But as I was going upstairs one night

I saw the young master lie with her

When Sunday morn comes, to his master Jack goes

Saying “Master, I must have some money.”

“Some money, John boy, are you going to be wed

For I fear you’ll pay dear for your honey.”

“How much money, John boy?” “Ten guineas” Jack says

“Ten guineas all in bright money?

When you are married, I will lay down

A thousand bright guineas for your honey.”

Then upstairs Jack goes, his clothes to tie up

And he’s tied them all up in a wallet

And out of the window he’s flung it so high

But the deuce* of a bet could he follow.

* deuce = devil

And when he’s got down, he’s gazed all around

And his wallet flung over his shoulder

And he is away to fair Norwich Town

And he’s left the young maid to his master.

Margaret Walters lives in Sydney, Australia and has a passion for unaccompanied traditional or trad-style songs, especially those absorbed during many visits to England between 1976 and 2013. She also sings Australian songs, including those by songwriter John Warner. Her albums are available on Bandcamp.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.