Submitted by Tim Edwards

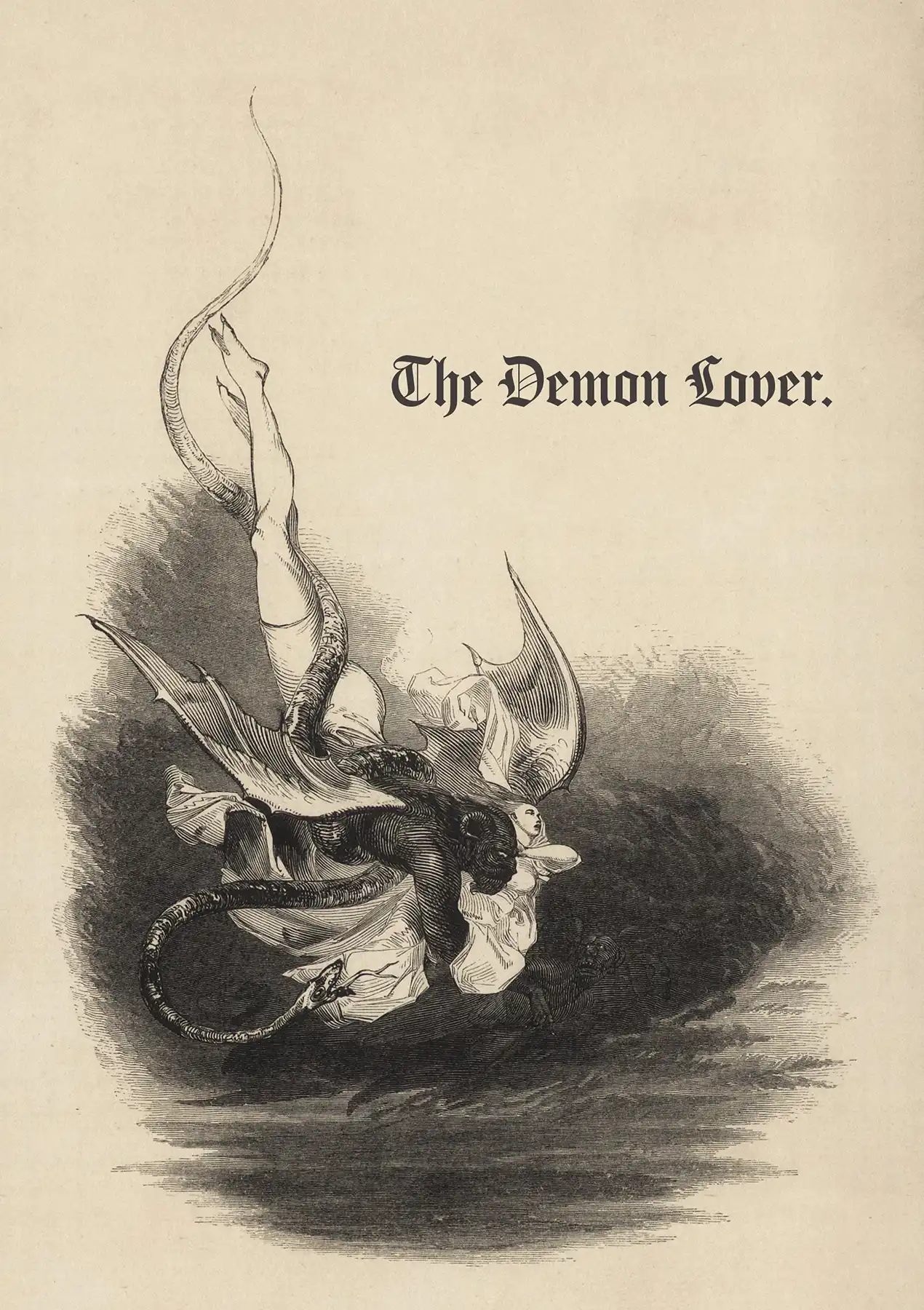

Also known as “The Demon Lover” or “The House Carpenter,” this ballad is 243 in the Child collection. I first heard it sung by Pentangle about 1970, and the story of the lost love reappearing after the traditional 7 years in demonic form captivated me and led me to learn it a few years later.

While some versions downplay the supernatural element, it was this that appealed to me. No version worked perfectly for me, so I ended up with a blend of verses from three different versions in Child, set to a tune I wrote. However, I never recorded the tune, and eventually found I’d forgotten it (lesson learned!), so I now sing it to a tune based on one I heard used for a version of “The Unquiet Grave.”

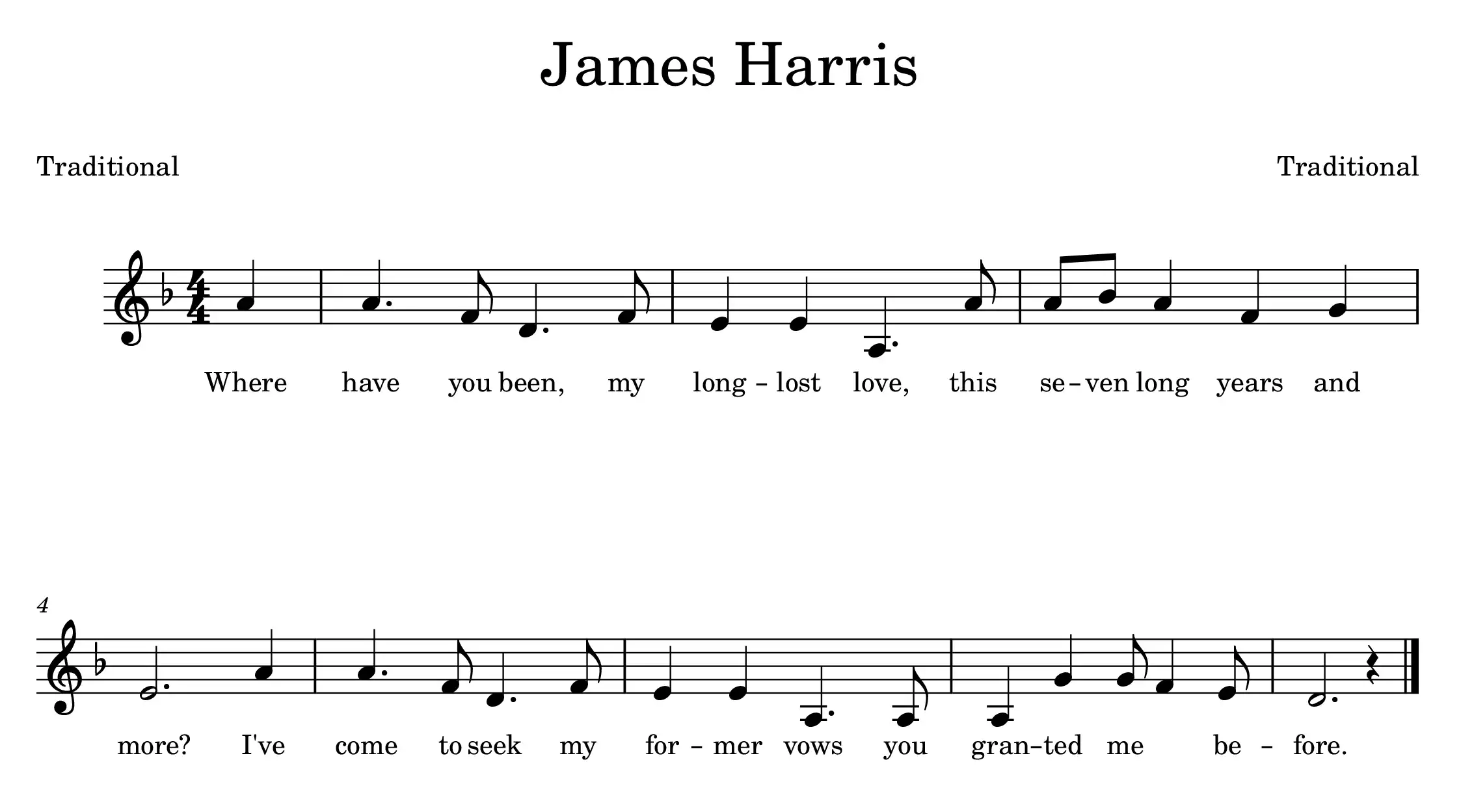

Listen to Tim’s recording of “James Harris:”

Lyrics

“Where have you been, my long-lost love,

This seven long years and more?

I’ve come to seek my former vows

You granted me before.”

“O hold your tongue of your former vows,

For they will breed sad strife.

O hold your tongue of your former vows

For I have become a wife.”

“I might have married a king’s daughter

Far far across the sea

But I refused the crown of gold

And it’s all for the love of thee.”

“If you might have married a king’s daughter

Yourself you have to blame

For I am married to a ship’s carpenter

And to him I have a son.”

“But have you any place to put me in

If I should with you gang

I’ve seven brave ships upon the sea

All laden to the brim.

“And I’ll build my love a bridge of steel

All for to help her o’er

Likewise a web of silk by her side

To keep her from the cold.”

And as they were walking up the street

Most beautiful for to behold

He cast a glamour o’er her face

That shone like the brightest gold

“O how do you love the ship?” he said

“How do you love the sea?

And how do you love the bold mariners

That wait upon you and me?”

“It’s well I love the ship,” she said

“It’s well I love the sea

But woe be to the dim mariners

That nowhere I can see!”

And they had no sailed a league, a league

A league but barely one

When she began to weep and to mourn

And to think on her poor wee son.

“O hold your tongue, my dear,” he said

“And let all your weeping be

For it’s soon I’ll show you how the lilies grow

On the banks of Italy.”

And they had not sailed a league, a league

A league but barely two

When she espied a cloven foot

From his gay robe sticking through.

And they had not sailed a league, a league

A league but barely three

When dark, dark grew his eerie looks

And raging grew the sea.

“O what are yon yon pleasant hills

That the sun shines so sweetly upon?”

“O yon are the hills of heaven,” he said

“Where you shall never win.”

“And whaten mountain is yon,” she cried

“All dreary with frost and snow?”

“O yon is the mountain of hell,” he cried

“Where you and I must go.”

He stuck the topmast with his hand

The foremast with his knee

He broke that gallant ship in twain

And sank her in the sea.

Tim Edwards writes: Born and brought up in Hertfordshire, I started singing folk songs in the early 70’s—initially in Greater London, and since the 90’s in Cheshire, as well as around the country at various festivals and clubs. Since lockdown, I have combined ‘live’ singing with online sessions with friends around the world.

My main interest is unaccompanied traditional song, although I sing a good number of contemporary pieces, including the occasional self-penned one. In particular, I love traditional ballads and lyrical songs.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.