by Jesse P. Karlsberg, Emory University

Jesse P. Karlsberg is senior digital scholarship strategist at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS) at Emory University. Jesse’s research analyzes connections between race, place, folklorization, and American music, focusing on the editions of The Sacred Harp and their attendant music culture. Jesse is editor-in-chief of of Sounding Spirit, a National Endowment for the Humanities–funded collection of digital and print editions of vernacular sacred American music co-published by ECDS and the University of North Carolina Press. An active Sacred Harp singer, teacher, composer, and organizer, Jesse is the vice president of the Sacred Harp Publishing Company, the non-profit organization that publishes The Sacred Harp, editor of Shape Notes: Journal of the Sacred Harp Publishing Company, and research director of the Sacred Harp Museum.

Introduction

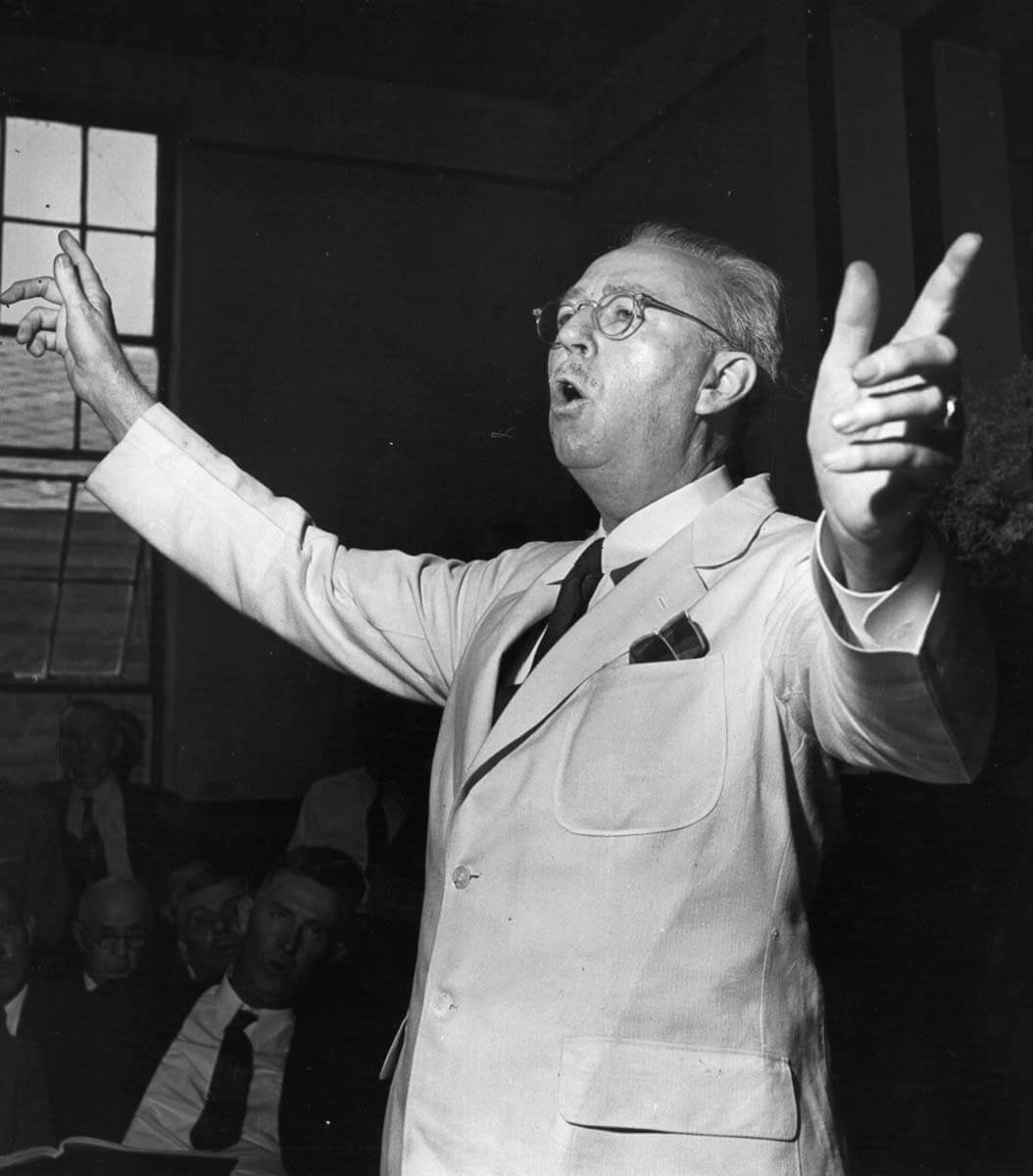

The state of Sacred Harp in 2018 would have been scarcely imaginable to those like folklorist George Pullen Jackson and singer and English scholar Buell Cobb, who questioned in the 1940s and 1970s, respectively, whether the style would survive past the year 2000. Both scholars pointed to its aging participants and a musical style seemingly irreparably out of fashion. [George Pullen Jackson, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands: The Story of the Fasola Folk, Their Songs, Singings, and “Buckwheat Notes” (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1933); George Pullen Jackson, The Story of The Sacred Harp, 1844–1944: A Book of Religious Folk Song as an American Institution (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 1944); Buell E. Cobb, The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1989).] Even advocates like Georgia singer and clothing plant manager Hugh McGraw, who ceaselessly promoted Sacred Harp singing to new audiences, set their sights on less ambitious targets than Sacred Harp’s current geography, envisioning a national Sacred Harp community stretching across the United States that has since materialized and been exceeded. As recently as 2008, the style was confined to the United States and pockets of England, Australia, and Canada. Today, Sacred Harp is sung on four continents in twenty-five countries. By the time you read this essay, the landscape may have shifted yet again.

Sacred Harp in Europe, Oceania, East Asia, and the Middle East is both a global and local phenomenon. Though vastly expanded in geography and demographic variety, the style is still a “subcultural sound,” a “micromusic,” convening small groups of people with strong community bonds often beneath the level of broad cultural attention [Mark Slobin, Subcultural Sounds: Micromusics of the West (Wesleyan University Press, 1993).] even as it regularly achieves local and even national press coverage. Despite its increasing reach, the new span of Sacred Harp singing is nonetheless limited in certain respects: First, the style has spread only to developed countries where US popular culture and media have a large imprint and garner a comparatively favorable reception. The style continues to attract an overwhelmingly white group of participants, with the exception of singings in East Asia, which have drawn Asian and white American expatriate participants. In each country, for the members of a local singing “class,” Sacred Harp’s reception follows and reacts to a history of economic and cultural relationships with America, and with the southern United States. The outsize presences of these cultural and economic forces far exceed that of Sacred Harp, and differently condition what participation in Sacred Harp means to new singers. Second, participation carries longstanding associations with deep roots in the “revival” of Sacred Harp in the United States. The style spreads abroad through transnational networks emulating practices associated with folk cultures of the southern United States. It also travels along art music and academic networks engaged in the cultivated celebration, performance of, and adaptation of material associated with these folk practices.

Even as economic and cultural relationships with the United States and an association with southern folk culture direct Sacred Harp’s spread, other factors facilitate the style’s international transmission. Features of Sacred Harp music and associated cultural practice have transcultural appeal. Aspects of Sacred Harp singing’s music culture engage participants in a full voiced, participation oriented, deeply spiritual, and accessible yet musically engaging practice and repertoire. Ethnomusicologist Ellen Lueck convincingly describes how the support of US-based Sacred Harp organizations, international singing groups’ “charismatic and enabled leadership,” and the affordances of the contemporary social media landscape have helped bolster Sacred Harp singing abroad. [Ellen Lueck, “Sacred Harp Singing in Europe: Its Pathways, Spaces, and Meanings” (Ph.D. dissertation, Wesleyan University, 2016), vii.]

This essay documents the present scope of Sacred Harp singing outside the United States and examines the eighty-five-year-old folklore genealogies that factor into the style’s recent spread. Although I focus on how what I call folklore’s filter made the expansion of Sacred Harp to new people and places possible, [Jesse P. Karlsberg, “Folklore’s Filter: Race, Place, and Sacred Harp Singing” (Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 2015).] I touch briefly on other factors in the dissemination of Sacred Harp beyond North America: the unique musical features and practices that support Sacred Harp’s adoption and the similarities and differences in the histories of transnational political, economic, and cultural exchange affecting the form of participation for many. These factors are critical to an understanding of Sacred Harp singing’s new international reach. First, however, I’ll briefly recount the history and practice of Sacred Harp singing itself.

Sacred Harp Singing

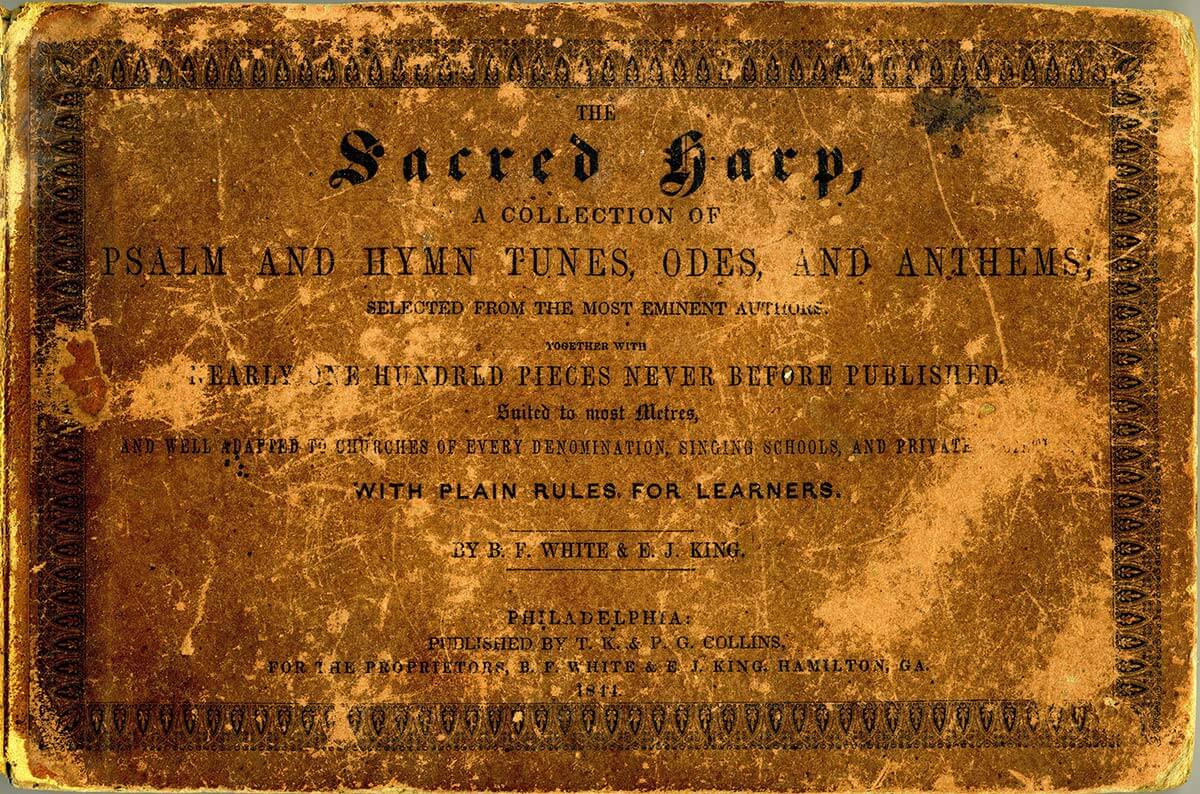

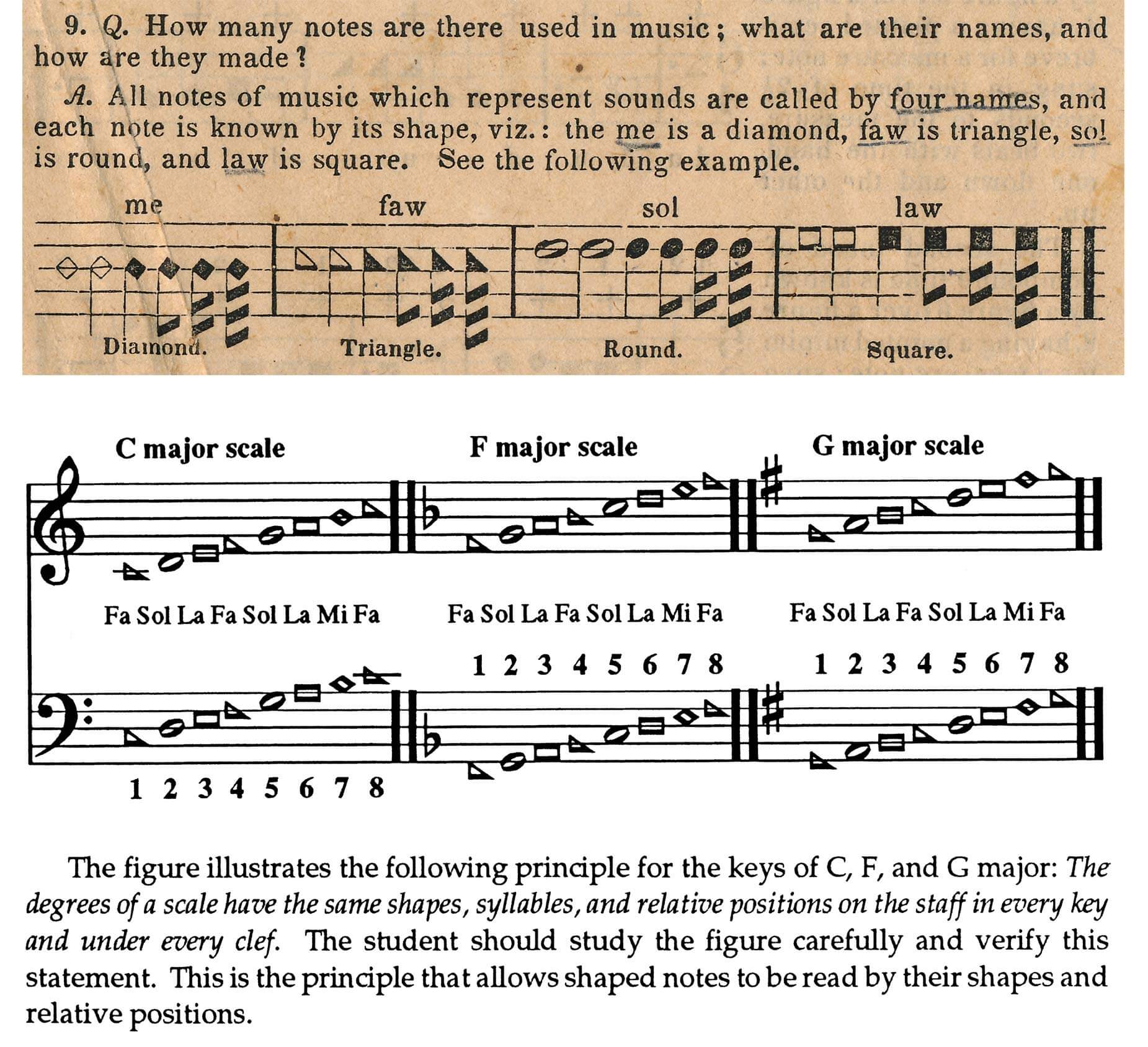

Sacred Harp is a practice of sacred community singing from the tunebook The Sacred Harp. First compiled in 1844 by West Georgians Benjamin Franklin White and Elisha James King, The Sacred Harp has been revised every generation or so by southern singer-teacher-composers. The book articulates a pedagogical system and adopts a bibliographic form, both of which have roots in eighteenth-century New England singing schools, and adopts a shape-note system of music notation dating to an 1801 Philadelphia tunebook called The Easy Instructor. The book features songs in three- and four-part harmony, mostly by American composers, in a variety of styles collectively described as dispersed harmony. The songs are settings of metrical poetry largely drawn from a corpus of English Protestant hymnody also widely incorporated into denominational hymnals.

Since its publication, The Sacred Harp has been connected to group singing institutions called conventions, which spread across the South in the decades after the 1845 establishment of the Southern Musical Convention in West Georgia. Conventions feature voluntary associations of singers seated by voice part in an inward-facing hollow square, at the center of which stand a succession of song leaders directing the group in one or more songs of their choice from the tunebook. The proceedings frequently last from morning to mid-afternoon, punctuated by short breaks for refreshments, announcements, and a sumptuous mid-day “dinner on the grounds.” The book’s compilers envisioned its sacred songs as suitable for worship by any Christian denomination, and its singers spanned the nineteenth century’s rural southern denominational landscape, encompassing men and women, and including black and white southerners. Yet race and gender affected the form of participation. Women rarely led songs in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and black singers were relegated to church balconies during slavery; singings became largely segregated after Reconstruction. The Sacred Harp’s connection to the music culture of singing conventions and its wide array of stakeholders committed to its success—thanks to their conscription in contributing to or revising the book—helping The Sacred Harp achieve wide adoption in a competitive landscape. The Sacred Harp outlasted an array of nineteenth-century competitors, surviving into the twentieth century as other books fell out of print and were supplanted by Sabbath School and gospel singing. By the early twentieth century, newer musical forms far exceeded Sacred Harp singing in popularity. To some, the style seemed outmoded and in need of modernization. Three competing groups revised the book in the wake of the original compilers’ deaths. These revisers adopted different approaches to making The Sacred Harp new while retaining its distinctive qualities that had long endeared the book to devoted followers. In balancing old and new, these editors attempted to redefine participation in a historical tradition as a modern. Embracing the conservative core of the style’s music, the most successful reviser modernized aspects of the book’s design and presentation, charting a path forward while setting the terms of what has remained an ongoing struggle for participants. [Jesse P. Karlsberg, “Joseph Stephen James’s Original Sacred Harp: Introduction to the Centennial Edition,” in Original Sacred Harp: Centennial Edition, ed. Joseph Stephen James and Jesse P. Karlsberg, Emory Texts and Studies in Ecclesial Life 8 (Atlanta, GA: Pitts Theology Library, 2015), v–xvi; Karlsberg, “Folklore’s Filter,” 25–74.] Like Sacred Harp’s early twentieth-century tunebook editors, singers today regard participation in the style as an ongoing, evolving practice, rather than the revival of something from the past, and sometimes struggle to articulate their relationship to this long and complicated history.

Folklore’s Filter

In the early twentieth century, participation in Sacred Harp singing was connected to a sense of local and personal belonging. The style’s depiction as a form of folksong beginning in the 1930s, which also involved the selection of particular local Sacred Harp groups as representative of traditional practice—what I call the style’s passage through folklore’s filter—provided an avenue for people with no personal connection to Sacred Harp’s original settings to imagine their active participation. To understand how Sacred Harp singing became folk music in the twentieth century, it is important to recognize that cultural phenomena do not objectively exist as folk practices. Instead a practice must be characterized as folk, usually by ideologically motivated cultural interveners. To describe a practice as folk entails detaching something occurring in the present and a casting it into what folklorist Barbara Kirschenblatt-Gimblett describes as folklore’s “peculiar temporality.” [Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, “Folklore’s Crisis,” The Journal of American Folklore 111, no. 441 (July 1, 1998): 281–327, doi:10.2307/541312.] This process is selective, a form of adaptation and rearrangement rather than a neutral transplantation. [David E. Whisnant, “Turning Inward and Outward: Retrospective and Prospective Considerations in the Recording of Vernacular Music in the South,” in Sounds of the South, ed. Daniel W. Patterson (Chapel Hill: Southern Folklife Collection, Manuscripts Department, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina, 1991), 165–81.] Relocating present practices in the past also imbues music cultures with a new set of values associated with the folk label, such as oral transmission, cultural isolation, and key aesthetic concerns. [Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, “Folklore’s Crisis”; David E. Whisnant, All That Is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995); Benjamin Filene, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory & American Roots Music (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000); Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).]

George Pullen Jackson, a professor of German at Vanderbilt University, first described Sacred Harp singing as a folk culture. Jackson’s scholarly interest in German Romanticism’s elevation of all things Volk led him to wonder why Americans didn’t care about their own folk culture. Despite vast historical and demographic differences between the United States and European nations, Jackson nonetheless “cast about” for a domestic Anglo-Celtic folk culture that might similarly serve as foundation for American national “poetic and musical art-developments.” [George Pullen Jackson, “Some Enemies of Folk-Music in America,” in Papers Read at the International Congress of Musicology Held at New York, September 11th to 16th, 1939 (New York: American Musicological Society, 1939), 77–83.] After stumbling upon Sacred Harp singing in 1926, [George Pullen Jackson, “The Fa-Sol-La Folk,” Musical Courier 93, no. 11 (September 9, 1926): 6–7, 10.] Jackson immediately interpreted the style as a folk culture in need of promotion: under threat by modernity, on the verge of inevitable transformation, and in need of protection and publicity to affect the form of its transformation. Jackson made saving Sacred Harp singing through trumpeting its history to the world his mission. Jackson also apprehended Sacred Harp music as a reservoir of primordial cultural matter of diverse but largely European and Anglo-Celtic origins transplanted and cultivated on American soil. This music, he believed, had matured in the imagined isolated cultural removes of the southern upcountry, and now sat ready for plucking and assimilating into a new national culture rooted in native American (but not Native American or African American) folksong. [On Jackson’s designation of Sacred Harp as an American folk music, see also John Bealle, Public Worship, Private Faith: Sacred Harp and American Folksong (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1997); Karlsberg, “Folklore’s Filter.”]

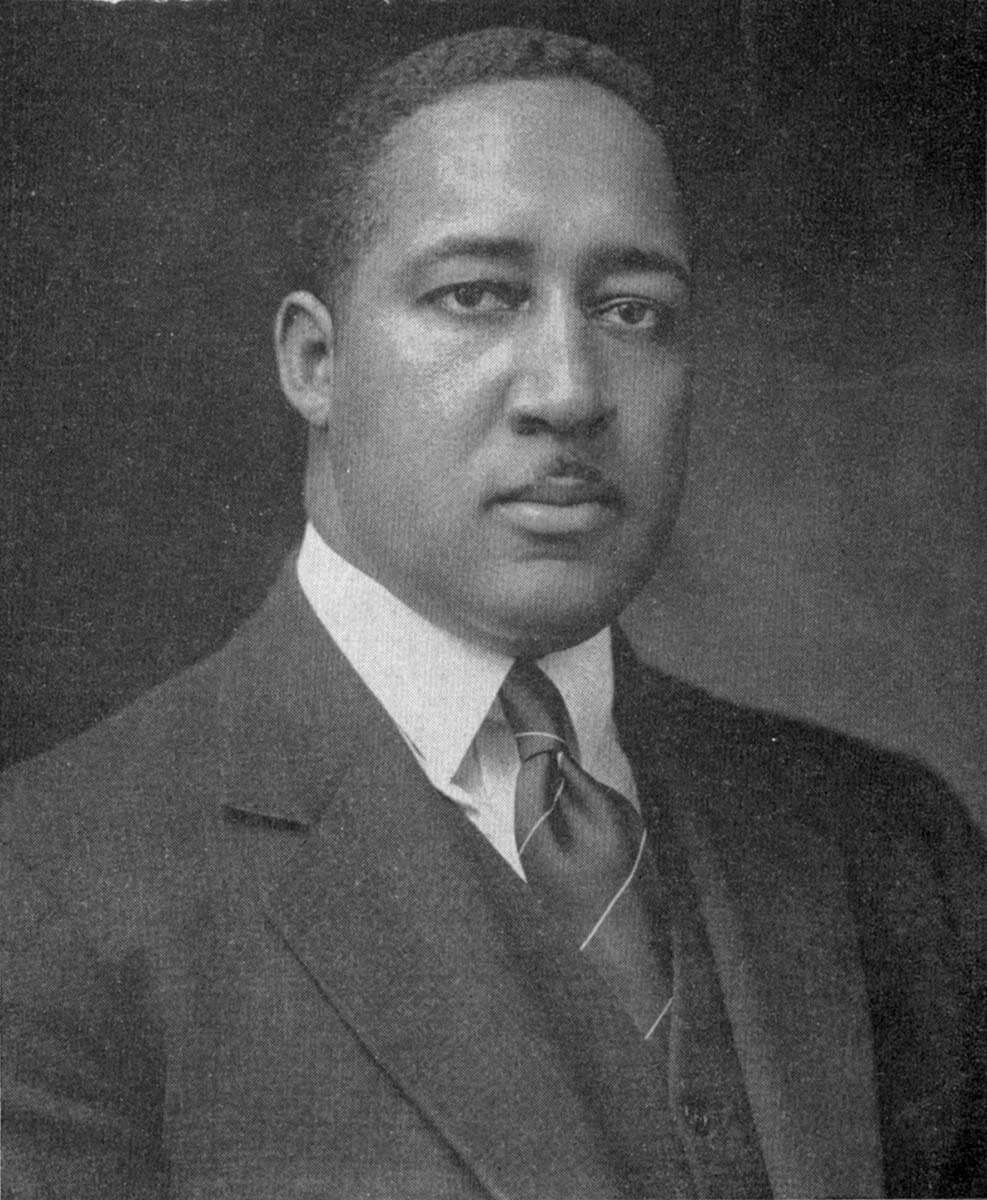

Jackson’s project galls today, and even in its time it was controversial. Inspired by the attention he believed northern philanthropists and a range of commenters on national American culture lavished on black spirituals, Jackson named Sacred Harp and related shape-note music “white spirituals.” Jackson argued that these songs were the source of black spirituals on the mistaken premise that first publication implies prior composition, [George Pullen Jackson, “The Genesis of the Negro Spiritual,” American Mercury 26 (June 1932): 243–55; Jackson, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands; George Pullen Jackson, White and Negro Spirituals: Their Life Span and Kinship, Tracing 200 Years of Untrammeled Song Making and Singing among Our Country Folk, with 116 Songs As Sung by Both Races (New York: J. J. Augustin, 1943).] a position long since discredited. [William H. Tallmadge, “The Black in Jackson’s White Spirituals,” The Black Perspective in Music 9, no. 2 (October 1, 1981): 139–60, doi:10.2307/1214194; Dena J. Epstein, “A White Origin for the Black Spiritual? An Invalid Theory and How It Grew,” American Music 1, no. 2 (July 1, 1983): 53–59, doi:10.2307/3051499.] He further suggested that these songs should thus be given pride of place over black spirituals in the American cultural and musical landscape. This position aligned Jackson with racial nativists, such as Richard Wallaschek, who drew on claims of originary and derivative styles to depict African and other musics as the product of inferior races of savage capacities. [Jackson himself did not hold such beliefs, and indeed argued that black imitation of white practices was evidence of African Americans’ equal abilities.] Jackson’s positions also placed him in tension with scholars such as W. E. B. Du Bois, who championed black spirituals as important expressions of the trauma of slavery and the middle passage. [W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1903), chap. 14.] Despite his bitterness at the lack of attention his “white spirituals” received, Jackson was an advocate for black cultural life in his hometown of Nashville, supporting the Fisk Jubilee Singers. Jackson also championed the art music of the city’s white elite (such as the Nashville Symphony Orchestra, which he founded).

Jackson did not achieve his ambitious goal of spawning a national culture rooted in Anglo-Celtic folk music. He did, however, publish widely on Sacred Harp, raising awareness of the style and carving paths along which future generations of scholars, festival promoters, and singers encountered the music, filtered through his folk characterizations. Jackson also presented Sacred Harp programs at numerous folk festivals and scholarly conferences, exposing the style to academics and folk music fans and locating it among other musics labeled as folk traditions. In addition, Jackson corresponded with leading composers such as Virgil Thompson, suggesting tunes to arrange, thereby contributing to the style’s incorporation into other music genres. In so doing, Jackson laid the groundwork for successive generations of musicologists and listeners to encounter the style through art music inspired by the style’s folk melodies.

Jackson’s representation of Sacred Harp as “white spirituals” contrasts with the scholarship of John W. Work III, a black professor of music at Fisk University, who also studied Sacred Harp in the 1930s. Although Work, like Jackson, described Sacred Harp as folksong, he instead wrote about the style as a form of black cultural expression. Work faced racial discrimination and professional pressures that limited his capacity to fund and conduct research on Sacred Harp singing. [John W. Work, Lewis Wade Jones, and Samuel C. Adams, Lost Delta Found: Rediscovering the Fisk University–Library of Congress Coahoma County Study, 1941–1942, ed. Robert Gordon and Bruce Nemerov (Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005), 1–26; Nathan Frazier et al., John Work III: Recording Black Culture, compact disc (Woodbury, TN: Spring Fed Records, 2008); Karlsberg, “Folklore’s Filter,” 127–80.] His lone publication on Sacred Harp, an article on a southeastern Alabama black community of singers, [John W. Work, “Plantation Meistersinger,” The Musical Quarterly 27, no. 1 (January 1, 1941): 97–106.] failed to dislodge Jackson’s misleading depiction of Sacred Harp as white with exceptional black practitioners. Nonetheless, Work’s scholarship did lodge a representation of black Sacred Harp in the scholarly record, which would lead successive generations of folk music scholars and folk festival promoters to the singers he documented.

Folk Festivals, New Audiences

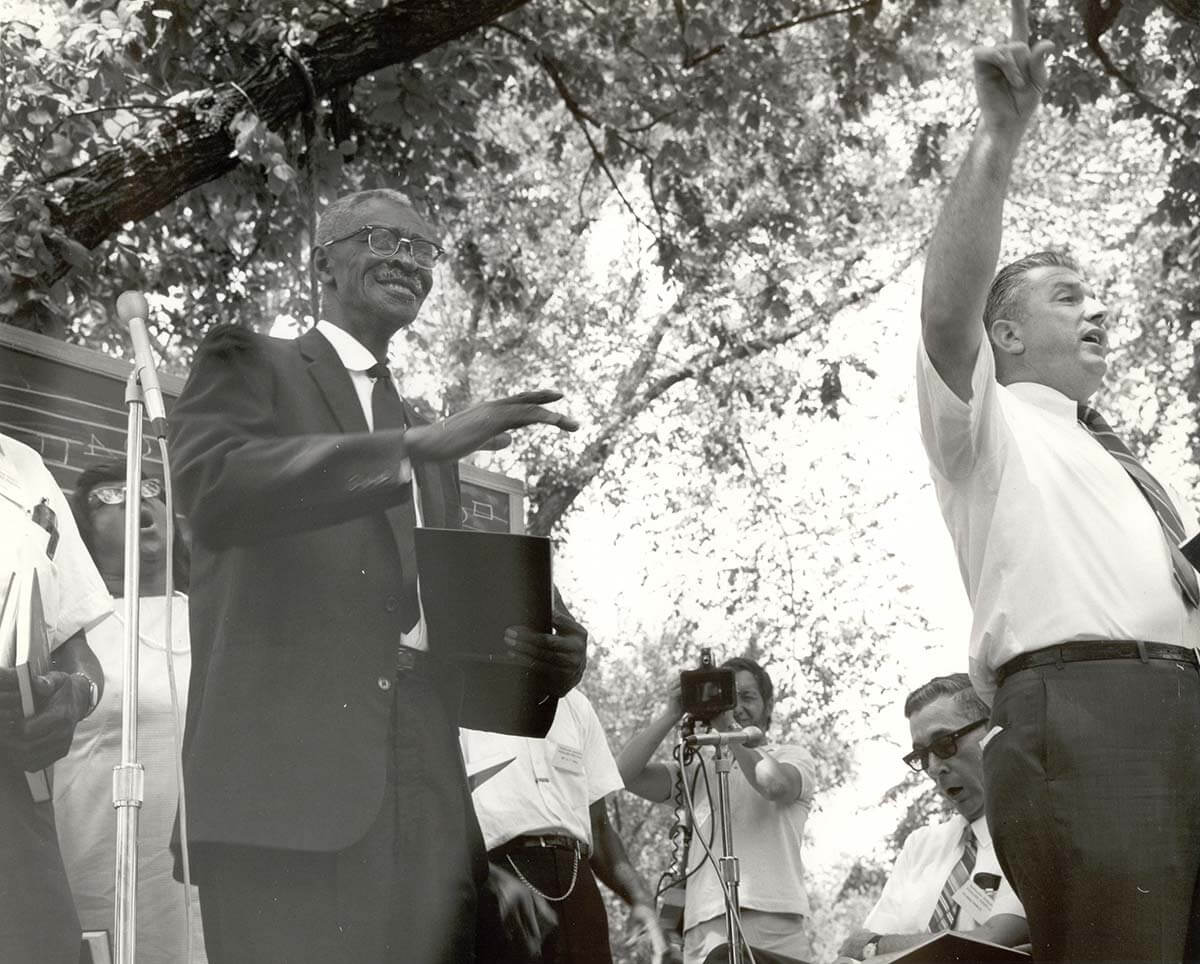

Folk festival promoters ventured through the channels that Jackson and Work carved to conduct fieldwork among black and white Sacred Harp singers during the folk revival of the 1960s and 1970s. These efforts led to a new spate of scholarship, as well as opportunities for black and white singers to perform at folk festivals across the United States. Sacred Harp singers made memorable appearances in Newport in 1964, and at the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife in 1970 and 1976. Festival promoters like Ralph Rinzler and George Wein were invested in the civil rights movement and regarded integrated programming as a way folk music could help further racial harmony. [Murray Lerner, Festival! (New York: Eagle Rock Entertainment, 2005); George Wein and Nate Chinen, Myself Among Others: A Life in Music (Da Capo Press, 2009).] In this context, far removed from the still-segregated spaces where Sacred Harp singers gathered in the southern United States, liberal and largely white festival audiences could associate Sacred Harp singing with idealized race relations and more easily identify with its white practitioners. [Karlsberg, “Folklore’s Filter,” 181–264.] Hugh McGraw, leader of the white group at many of these festivals, drew on his considerable business savvy to reach out to audiences with the hope of attracting new participants to the tradition.

McGraw’s outreach and the recontextualization of Sacred Harp at folk festivals led to increased interest and participation. Many new singers encountered Sacred Harp through folk music, at both large festivals and smaller gatherings. John Feddersen, a fifty-year veteran of Sacred Harp singing in North Carolina, first encountered Sacred Harp at the 1970 Festival of American Folklife. [Dan Kane, “Archaic Sounds of Shape-Note Singing Resound in Raleigh,” News Observer, March 22, 2015.] Others first heard Sacred Harp in participatory folk song circles, such as those held at upstate New York’s Fox Hollow folk festival. The classical contexts in which Sacred Harp melodies could be heard, thanks to Jackson’s earlier efforts, also drew newcomers into the style. Washington, DC, singer Steven Sabol, for example, first heard Sacred Harp melodies at a concert featuring an arrangement of a Sacred Harp tune by Samuel Barber, and later found his way to Sacred Harp singing by perusing scores, recordings, and reissued tunebooks at university libraries.

These choral, academic, and folk festival manifestations of Sacred Harp’s rite of passage through folklore’s filter contributed to the earliest institutionalization of Sacred Harp singing outside the southern United States. By the time Alabama and Georgia singers performed at the 1970 Festival of American Folklife, folk music enthusiasts had already begun singing Sacred Harp at the Folklore Society of Greater Washington, leading Rinzler to promote the group’s meetings to attendees from the festival stage. [Sacred Harp Singers, Festival Recordings, 1970: Wade and Fields Ward with Kahle Brewer; Sacred Harp Singers, CD transfer, 1970, fp-1970-rr-0039, Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.] Singings began at the Ark Coffeehouse in Ann Arbor, Michigan, before 1973. There, folk music enthusiasts and academics sang together, embracing the longstanding history of University of Michigan musicology scholarship on American musics related to Sacred Harp. The group instituted an annual all-day singing after later Sacred Harp revision consultant David Warren Steel arrived in 1973 as a musicology graduate student. [David Warren Steel, “Ann Arbor singings, was, Minutes and Question,” Fasola Singings list, April 1, 2015.] These academic, choral, and folk genealogies collided at Wesleyan University in 1976, where a planned concert by Vermont folkie and choral conductor Larry Gordon’s Word of Mouth Chorus became the first annual New England Sacred Harp Convention, with McGraw as chairman and Wesleyan composer and music professor Neely Bruce as vice chairman. At this first Sacred Harp singing convention outside the South these paths, the inheritance of Jackson’s scholarship, converged.

The spread of Sacred Harp singing in the United States intensified through the 1980s and 1990s as southern singers supported new participants in founding singing after singing across the country. [On the geographical contours of this spread, see Jesse P. Karlsberg and Robert A. W. Dunn, “Mapping the ‘Big Minutes’: Visualizing Sacred Harp’s Geographic Coalescence and Expansion, 1995–2014,” Southern Spaces Blog, January 23, 2018.] Southern support for these fledgling conventions frequently arrived in the form of a bus full of singers, chartered by Jacksonville, Alabama, singer and retired schoolteacher Ruth Brown. Ruth Brown’s bus helped forge networks of reciprocal travel that sustained these new singings by connecting singers, old and new. Many members of these burgeoning populations imagined their singings as outposts of a style with a homeland centered in the southern communities that George Pullen Jackson’s scholarship had enduringly marked as “traditional.”

Like the folk festival audiences that heard black and white renditions of what Jackson called “white spirituals,” the late twentieth-century spread of Sacred Harp singing was largely white. However, thanks to folklore’s, classical music’s, and the academy’s secularizing tendencies, Sacred Harp began to include participants of a much wider array of political and religious backgrounds. New participants were also increasingly economically and educationally diverse, but skewed toward higher class and education levels than southern singers thanks to this new population’s overlap with the academy.

Transportable Features

Sacred Harp’s growth in the 1980s and 1990s, and its subsequent international expansion, have been facilitated by the set of practices that have developed around singing from the tunebook. These practices are emotionally and spiritually powerful, conducive to community formation, and particularly transportable. Ethnomusicologist Kiri Miller has argued that the iconicity of Sacred Harp’s hollow square seating formation, the emotional associations singers build around the configuration, and the ease with which it can be set up renders it a kind of “portable homeland.” [Kiri Miller, Traveling Home: Sacred Harp Singing and American Pluralism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008).] Lueck articulates how a Sacred Harp singing convention “is a space that provides a familiar structure and social order across geographic and cultural distance” with a “shared event choreography which is legitimized through performative keys which rely on that choreography for interpretation, and social codes which police the space” while also affording a context “in which singers can express their belonging to the community-at-large.” [Lueck, “Sacred Harp Singing in Europe,” 46.] Sacred Harp’s participatory orientation, which includes not only the hollow square formation (in which singers sit facing each other rather than an audience) but the rotation of leaders at singings and an openness to all who would wish to sing regardless of identity and singing ability, lends the style to community formation through music making. [Robert T. Kelley, “Harmonious Union: How Sacred Harp Brings People Together,” The Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 2, no. 1 (March 14, 2013).] Finally, for many participants in a variety of political contexts, Sacred Harp’s full-voiced singing and status as a regular opportunity to gather with friends mean it can serve as a powerful source of emotional and spiritual renewal, and as an antidote for perceived lacks in contemporary society.

The result as Sacred Harp continues to spread, Lueck argues, is a transnational community, [Ellen Lueck, “The Old World Seeks the Old Paths: Observing Our Transnationally Expanding Singing Community,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 3, no. 2 (November 12, 2014).] in which singers frequently articulate the style’s capacity to bridge “vast differences” rendering singers akin to “family.” [These tropes, of seemingly unbridgeable differences and of the Sacred Harp network’s status as a “family,” implying greater closeness even than “community,” frequently emerge in memorial lessons, in officers’ remarks at the end of a day of singing, and in private conversations on car rides to and from singings and at social gatherings among singers.] The transcultural appeal of these aspects of Sacred Harp’s music culture are often what singers themselves offer in explaining their participation.

Spread to Europe

The first flowerings of Sacred Harp in Europe grew directly out of the style’s folk-inflected genealogies and histories, in particular the mix of folk music and its performance by choral ensembles, and were fed by the style’s transportable features. Sacred Harp’s “portable homeland” initially arrived beyond North America in the wake of workshops and performances held in the United Kingdom in the early 1990s and led by Northern Harmony, a touring ensemble based in Vermont and directed by Larry Gordon. [Several English performing ensembles had recorded Sacred Harp songs prior to the Northern Harmony tour. Gordon’s presence brought together several English singers interested in Sacred Harp thanks to these earlier performances and introduced additional key early organizers of English Sacred Harp singing to the style. Steve Fletcher, “Two Decades of Shape-Note Singing in the UK: A Personal Perspective” (Presentation, Sing Oxted, Oxted, United Kingdom, November 15, 2014). On Gordon’s particularly influential 1994 tour of the United Kingdom, see also Lueck, “Sacred Harp Singing in Europe,” 95–97.] In the United Kingdom, English revivalists of the nineteenth-century congregational hymn singing practice known as “West Gallery music” learned and taught each other to sing shape-notes, purchasing copies of The Northern Harmony (a shape-note tunebook Gordon had co-edited in which New England and English tunes feature prominently), as well as The Sacred Harp. In 1995, Neely Bruce led a quartet of young singers from Connecticut and Massachusetts on a United Kingdom tour. Like Gordon, Bruce mixed concerts with workshops during his English tour, and encountered singers who recognized Sacred Harp singing as related to a shared legacy of nineteenth-century religious folk song. Those who attended Bruce’s and Gordon’s concerts came together with singers who encountered Sacred Harp in scholarly writing or available recordings to stage the first of what they styled a “singing day” in 1995. The following year, with the participation of New England Sacred Harp singers, English singers organized the first United Kingdom Shape-Note Convention, using The Northern Harmony and The Sacred Harp as tune books. [Fletcher, “Two Decades of Shape-Note Singing in the UK.”] Sacred Harp singing grew steadily in England in subsequent years, largely among a population equally enthusiastic about folksong and folk dancing. Individual singers’ pathways into Sacred Harp in England were diverse from the start, and in the late 1990s and into the 2000s the backgrounds of new English participants grew increasingly varied. But Sacred Harp singing’s twentieth-century passage through folklore’s filter made its journey across the Atlantic possible. Jackson’s early associations between Sacred Harp and Anglo-Celtic folksong, as well as his promotion of the style as material for high status art music performed by classical and elite choral ensembles, made possible the connections that first carried Sacred Harp to England and later fueled its subsequent growth. By 2018, English singers could attend twenty-five annual singings from The Sacred Harp, as well as an expanding list of monthly and weekly gatherings in cities across the country. [“Calendar 2018,” United Kingdom Sacred Harp & Shapenote Singing, accessed February 1, 2018.]

The academic and performing legacy of Sacred Harp’s folklorization also contributed to the establishment of Sacred Harp singing in Ireland, where the rapid growth of a young and enthusiastic population of singers in Cork precipitated increased transatlantic and intra-European travel to singings. As I recounted in 2011, “Sacred Harp singing was introduced to Ireland in 2009 with the founding of a music ensemble at University College Cork (UCC) led by ethnomusicologist Juniper Hill,” a former student of Neely Bruce. “Hill’s students soon established a singing at a community art space in downtown Cork,” and interest in participating quickly outstripped the classroom where Hill had established the singing. [Jesse P. Karlsberg, “Ireland’s First Sacred Harp Convention: ‘To Meet To Part No More,’” Southern Spaces, November 30, 2011. On the establishment of Sacred Harp in Ireland and the first Ireland Convention, see also Robert Wedgbury, “Exploring Voice, Fellowship, and Tradition: The Institutionalised Development of American Sacred Harp Singing in Cork, Ireland and the Emergence of a Grassroots Singing Community” (M.A. thesis, University College Cork, 2011); Alice Maggio, “Regional Report: First Ireland Sacred Harp Convention,” The Trumpet 1, no. 2 (2011): vi; Lueck, “Sacred Harp Singing in Europe,” 119–29.] The first Ireland Sacred Harp Convention, held in March 2011, attracted unusually large contingents of American singers, as did subsequent annual sessions. Ethnomusicologist Jonathon Smith argues that these singers were drawn to Ireland in part because of a perception, more imagined than real, of Sacred Harp’s (and of Sacred Harp singers’) Celtic roots. [Jonathon Smith, “Celtic Imaginaries: The Sacred Harp, Ireland, and the American South” (paper presentation, International Council for Traditional Music, Limerick Ireland, July 17 2017).] Dating to George Pullen Jackson’s articulation of Sacred Harp’s “far southern fasola belt” populated by “Scotch-Irish and German, with a small ingredient of English,” [Jackson, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands, 158–59. Jackson drew both population data about and support for his veneration of the group he identified as whites of the southern uplands from John C. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1921).] Sacred Harp singing’s Celtic connection both detracts from equally significant historical influences at odds with Jackson’s political project and lays groundwork for the style’s valorization as tied to the music of the British Isles. Most Irish singers recognized Sacred Harp singing’s capacity for community formation, rather than its imagined Irish roots, as key to its success locally. Yet this geographical dimension of Jackson’s characterization of the style as folksong contributed to the international appeal of early Ireland Sacred Harp conventions, in Ireland and beyond. [Karlsberg, “Ireland’s First Sacred Harp Convention;” Smith, “Celtic Imaginaries.”]

Video recording of the first Ireland Sacred Harp Convention, March 2011. Courtesy of Cork Sacred Harp.

Sacred Harp singing similarly reached Germany via the Northern Harmony tour that introduced Sacred Harp to England. Jutta Pflugmacher, a folk music enthusiast from Bündingen, Germany, had attended one of these early concerts, singing briefly with English Sacred Harp singers. Back in Germany, she organized a stop on the 2010 Northern Harmony tour in her home town. Motivated to bring Sacred Harp singing to Germany, Plugmacher reached out to Keith MacDonald, an English expatriate and Sacred Harp singer. She also arranged for Aldo Ceresa, a New York–based singing school teacher, to present two workshops in her region, accompanied by a traveling group of English singers. [Jesse P. Karlsberg, “New Writing on Sacred Harp in Europe,” JPKarlsberg.com, (March 14, 2013); Michael Walker, “German Singing Schools: Sacred Harp Comes to the Land of J. S. Bach,” The Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 1, no. 1 (March 28, 2012).] A fledgling group from Bremen who had discovered Sacred Harp through the Internet traveled to attend these workshops. [Harald Grundner, “Wie Alles Begann,” Sacred Harp Bremen, accessed August 24, 2015.] Young Sacred Harp singers from England and Ireland living temporarily in Germany added to these emergent groups. These singers hosted their first all-day singing in January 2012, followed by Germany’s first convention in June 2014. Echoing Jackson, English singer Michael Walker noted in a report on the early German singing schools that Germany lacks the “natural points of connection with the British/Celtic origins of many of the tunes and with the religious poetry of The Sacred Harp.” [Walker, “German Singing Schools.”] The relatively few American visitors to the first German singings rarely describe their trips using the language of “returning home” that characterize some singers’ motivations for visiting singings in Ireland. No Sacred Harp tour of Germany has materialized to match the 2007 tour of England that included visits to the gravesites of prominent hymn writers whose poetry is included in The Sacred Harp. As singing in Germany has spread to new cities since 2014, the network has become an increasingly self-sufficient regional core accelerating central Europe’s Sacred Harp growth. [Jesse P. Karlsberg, “Regional Roots: Growing Sacred Harp in the Netherlands, Alaska, and British Columbia,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 4, no. 2 (December 31, 2015).] Yet the beginnings of Sacred Harp in Germany nonetheless evince connections to the same folksong-inspired performing ensembles that facilitated the spread of Sacred Harp to England and Ireland.

Video recording of the first Germany Sacred Harp Convention, May 2014. Courtesy of Sacred Harp Bremen.

Poland, like Germany, “is a country with its own rich indigenous linguistic, cultural, musical, and religious heritage.” [Walker, “German Singing Schools.”] Many of Poland’s first Sacred Harp singers encountered the style at events organized by individuals with connections to the spread of Sacred Harp in other parts of Europe, and with roots in the academic study of Sacred Harp and related styles. Sacred Harp singing spread to Poland after a weeklong singing school at the Jarosław Early Music Festival taught by musician and ethnomusicologist Tim Eriksen. (I served as Eriksen’s assistant.) [Eriksen’s Polish wife and manager Magdalena Zapendowska-Eriksen arranged for the workshop. Then an English professor, Zapendowska-Eriksen had learned of Sacred Harp singing in 2003 through studying English hymnist Isaac Watts and first attended singings when visiting Western Massachusetts in the United States to conduct research on Emily Dickinson in 2005. She began hosting a regular gathering to practice Sacred Harp songs at her home in 2006. A video recording of the singing that marked the conclusion of the singing school is at Timothy Eriksen, Sacred Harp Singing in Jaroslaw, Poland, e video (Jarosław, Poland, 2008).] An eclectic musician with roots in punk, grunge, folk, and world music, Eriksen first encountered Sacred Harp singing through the field recordings of folklorist Alan Lomax. [Lomax first encountered Sacred Harp singers during a 1942 recording session in Birmingham, Alabama, in collaboration with George Pullen Jackson.] Eriksen, a former member of the quartet Bruce brought to England in 1995, later entered a doctoral program in ethnomusicology at Wesleyan University. Participants in the 2008 Jarosław singing school returned home to establish weekly Sacred Harp singings in Warsaw and Poznan. This growing group of singers collaborated with Alabama Sacred Harp singer and Camp Fasola co-founder David Ivey to arrange for a northern Poland location for a 2012 session of the annual singing school. Ivey organized first session of the then nine-year-old singing school held outside Alabama in response to the growing interest in the style across the continent. [Jesse P. Karlsberg, “‘Come Sound His Praise Abroad’: Sacred Harp Singing across Europe,” Country Dance and Song Society News, Winter 2012, 9–12; Jesse P. Karlsberg, “Sacred Harp, ‘Poland Style,’” blog, Southern Spaces Blog (February 27, 2013); Gosia Perycz, “A Hollow Square in My Homeland: Bringing Camp Fasola to Poland,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 2, no. 1 (March 14, 2013); Fynn Titford-Mock, “Celebrating Sacred Harp in Europe, September, 2012,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 2, no. 1 (March 14, 2013). On Sacred Harp’s arrival in Poland, see also Lueck, “Sacred Harp Singing in Europe,” 108–19.]

Two video recordings of the Sacred Harp singing held to mark the conclusion of Tim Eriksen’s weeklong singing school at the Jarosław Early Music Festival, September 2008.

Sacred Harp singing first reached Poland as “Early Music” rather than “folk music.” Yet the possibility of this characterization also owes a great deal to the framing George Pullen Jackson introduced. Depicting Sacred Harp as “America’s earliest music” was key to Jackson’s hopes for inspiring a new national culture rooted in American Anglo-Celtic folk tradition. Singers and folklorists alike have championed Sacred Harp’s antiquity in describing and promoting the style across the twentieth century. The rationale for including a contemporary music culture practiced across the United States and England in the Jarosław Early Music Festival, an event primarily featuring the music of seventeenth-century and earlier European music, relies on the folklorization of the style. [Jesse P. Karlsberg, “Resonance and Reinvention: Sounding Historical Practice in Sacred Harp’s Global Twenty-First Century” (paper presentation, Stichting voor Muziekhistorische Uitvoeringspraktijk [Foundation for Historical Musical Performance Practice], Utrecht, Netherlands, August 29, 2015).]

Just as European and American singers helped establish Sacred Harp singings in England, Ireland, Germany, and Poland, traveling singers have contributed to the expansion of Sacred Harp singing across Europe and beyond since 2008. An Alabamian stationed in South Korea and a Cork singer there teaching English established shortly lived singings in South Korea in 2012. Sacred Harp’s roots in Australia extend to two Australians’— Shawn Whelan and Natalie Sims—encounter with the style while Sims was completing a postdoctoral fellowship at a New England educational institution in 1998. Plans to hold an all-day singing came together in 2012, after Belfast singer Eimear Craddock, who first sang Sacred Harp in Cork, moved to Sydney. [Steven Levine, “Sacred Harp Down-Under: The First Australian All-Day Singing,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 2, no. 1 (March 14, 2013).] Sacred Harp singing briefly flourished in Hong Kong after American singer, Aaron Kahn, who had begun singing Sacred Harp stateside and briefly ran a singing in Paris, moved to the area. Tim Cook, long-active in Sacred Harp and Christian Harmony singing in Alabama, established the first singing in Japan in 2015 with Peter Evan shortly after moving to the country. Israel’s Sacred Harp singing was founded by Israeli musician, Ophir Ilzewski, who came across the style by chance in Norwich, England, and honed his skills at the fall 2014 second European session of Camp Fasola. As English, Irish, Polish, and American singers moved internationally, they crossed paths with individuals and small groups who first experienced Sacred Harp independently, connecting these singers to an emerging international network of singers, and urging the adoption of practices associated with folksong, its revival, and the filters of its scholarly genealogies.

Nationalisms

The places that encompass the contemporary landscape of Sacred Harp singing feature dramatically different social and political contexts, but all are political allies of the United States where American popular culture has a large imprint. Sacred Harp singing operates subculturally, affecting the lives of small numbers of singers in each city or region. The massive commercial enterprises and political and economic ties that encourage adoption of American culture thus have little direct impact on Sacred Harp singing. [An important exception is the 2003 Hollywood film Cold Mountain, which featured two Sacred Harp songs. The film generated considerable publicity for Sacred Harp singing and attracted many new singers to the style. See Jesse P. Karlsberg, Mark T. Godfrey, and Nathan Rees, “The Cold Mountain Bump: Hollywood’s Effect on Sacred Harp Songs and Singers,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 2, no. 3 (December 31, 2013). In my fieldwork in Europe I have encountered several singers who trace their introduction to Sacred Harp singing to the film.] Despite its absence from popular awareness in the countries where singings are held, Sacred Harp’s international reception refracts political and cultural relationships with the United States and its folksong. Each country’s political allegiance with the United States makes possible the reciprocal travel that strengthens emerging singings, and the largely favorable conceptions of American culture form a background context in which Sacred Harp’s “Americanness” does not seriously detract from and may even contribute to the singing’s attraction and positive reception.

In England, perceived historical ties between Sacred Harp and English West Gallery singing intrigue a number of singers, particularly those from England and New England who were active during the period when Sacred Harp singings were initially established in the United Kingdom. Some English Sacred Harp singers are deeply involved in an English revival of West Gallery music. The Northern Harmony tunebook adopted alongside The Sacred Harp at early English singings gained popularity in part because it features arrangements of West Gallery tunes, signifying to some a connection between the English and American genres. Relatedly, several early English Sacred Harp singers preferred New England fuging tunes to other songs in The Sacred Harp, drawing on the genre’s historical relationship to the West Gallery repertoire. One English singer, Chris Brown, has examined music manuscripts to trace the migration of tunes from the United States to the United Kingdom around 1800, shedding light on a historical transatlantic exchange that parallels Sacred Harp’s spread to the United Kingdom in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. [Chris Brown, “American Tunes in West Gallery Sources,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 3, no. 2 (November 12, 2014).] He has also presented on the English roots of Sacred Harp singing, focusing not on the book’s predominantly American tune writers, but on its hymn writers, who are predominantly English. [Chris Brown has taught classes on English hymn writers at sessions of Camp Fasola held in Poland and in Alabama in the United States.]

In Poland, a post–Cold War embrace of American and European cultural, economic, and political models [See Derek E. Mix, “Poland and Its Relations with the United States: In Brief” (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, November 17, 2015). ] introduces a narrative in which Sacred Harp’s presence represents values identified with the United States, such as freedom of expression, as well as the allegiance between the two countries. The location of the first two European sessions of Camp Fasola in Kashubia, a region in the country’s north that is now expressing renewed celebration and revival of local cultural practices as well as ethnic folk traditions, facilitates a logic of cultural exchange with the West as a context for engaging with the presence of Sacred Harp singing in the area. In fall of 2014, with Russia newly embroiled in conflict with Ukraine, tour guides for an American group visiting to participate in Sacred Harp singing placed the current conflict along the Russia-Ukraine border in the context of a centuries-long history of military and political domination of Poland by German and Russian forces. Their geopolitical narrative implicitly conscripted American tourists as Polish allies. [I traveled as a member of the American tour group thanks to support from the Sacred Harp Musical Heritage Association and Emory University’s Laney Graduate School’s professional development support funds. On the September 2014 American Sacred Harp trip to Europe, see also Kathy Williams, “A Long Time Traveling: A Sacred Harp Tour to the UK Convention, Camp Fasola Europe, and the Poland Convention,” Sacred Harp Publishing Company Newsletter 4, no. 1 (May 28, 2015).] David Ivey, the camp director, articulated a similar cultural allegiance at the first Camp Fasola Europe in 2012. During a performance by a Kashubian folk music and dance troupe that emphasized the group’s ability to celebrate Kashubian cultural heritage thanks to the absence of Soviet domination, Ivey stated that he never could have imagined Sacred Harp in Poland before the fall of the Iron Curtain. [Karlsberg, “Sacred Harp Singing across Europe.”] Both Polish and American participants in the evening’s cultural exchange pointed to its ability to celebrate and reiterate political ties between the two countries.

I offer these two examples of Sacred Harp’s embeddedness in national political and cultural relationships with the United States to suggest that understanding folklorization’s impact on the style’s internationalization requires negotiating America’s outsize presence and the effects of that presence on subcultural sound. Different national contexts, as well as the varied positions individual singers and their identity categories occupy with respect to these contexts, affect what Sacred Harp singing means to participants. [Lueck notes that although singers celebrate the national diversity of major singings “as a sign of community growth and cooperation,” actually expressing national identity can garner a mixed reception, as when singers “explicitly reference historical anti-British sentiments” through leading one of the handful of American patriotic songs in The Sacred Harp. See Lueck, “Sacred Harp Singing in Europe,” 188, 190–91.] Understandings of Sacred Harp singing’s practices as democratic and pluralistic also reveal the embeddedness of folksong-inspired rhetoric in geopolitically bounded Western political and cultural values. As Lueck notes, even the transportability of Sacred Harp’s features “relies on the freedom of participants to create their own spaces of identity, and the freedom to pursue their affinity.” [Lueck, “Sacred Harp Singing in Europe,” 278.] Further research might shed light on the ramifications of America’s geopolitical alliances and cultural exports on musical subcultures abroad.

Conclusion

As Sacred Harp singing continues to spread across the globe, the style can seem increasingly unmoored from the nostalgic, elegiac discourse that painted Sacred Harp singing as the dying art of an isolated “lost tonal tribe.” But the roots of this current transformation extend back to the style’s passage through folklore’s filter and to the networks of scholars and singers that flourished in its wake. Folklorization made the style’s expansion beyond its southern and national boundaries possible, and indelibly affected the form and direction of its growth.

Much work—ethnographic, theoretical, and archival—remains to be done to describe the social contexts in which Sacred Harp singing’s ongoing geographical and demographic shifts are taking place. It is important to think about how scholars’ characterization of the style as a folk music and some singers’ depiction of it as a venerable practice rooted in the antebellum southern United States may continue to affect the contours of its spread. It is equally necessary to ask how the style’s association with America affects its reception in countries with varied political and cultural relationships with the United States. Even as many new singers emphasize the transcultural ability of Sacred Harp singings to serve as meaningful cathartic gatherings conducive to community formation, more research might shed light on how singers with different backgrounds in different parts of the globe respond to the style’s practices. As Sacred Harp, now ascendant, travels to new corners of the globe, it is important to be mindful of who and where it does reach, and who and where it does not.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Meredith Doster, Alan Pike, Allison Thompson, and an anonymous reader for CD+SO for their suggestions on how to improve earlier drafts of this essay. Thanks to Ellen Lueck, fellow researcher of Sacred Harp singing’s international expansion, for her generosity in sharing ideas and fieldwork. Thanks to the archivists at the Alabama Department of Archives and History, Wesleyan University Archives and Special Collections, and the Library of Congress and to individual singers in the United States and Europe for their efforts documenting, preserving, and making accessible images and video recordings documenting Sacred Harp’s history and present expansion. Thanks to my wife, Lauren Bock, for supporting and sometimes accompanying me on my fieldwork trips in Europe and the United States. Thanks, finally, to the Sacred Harp singers who welcomed me into their homes and helped me formulate the ideas in this article over many delightful hours of conversation.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Isaac Banner

Isaac Banner Seth Tepfer

Seth Tepfer Christa Torrens

Christa Torrens Ellie Shogren

Ellie Shogren Sharon Green

Sharon Green Dilip Sequeira

Dilip Sequeira