by David Millstone and Allison Thompson

Download a PDF version of this article

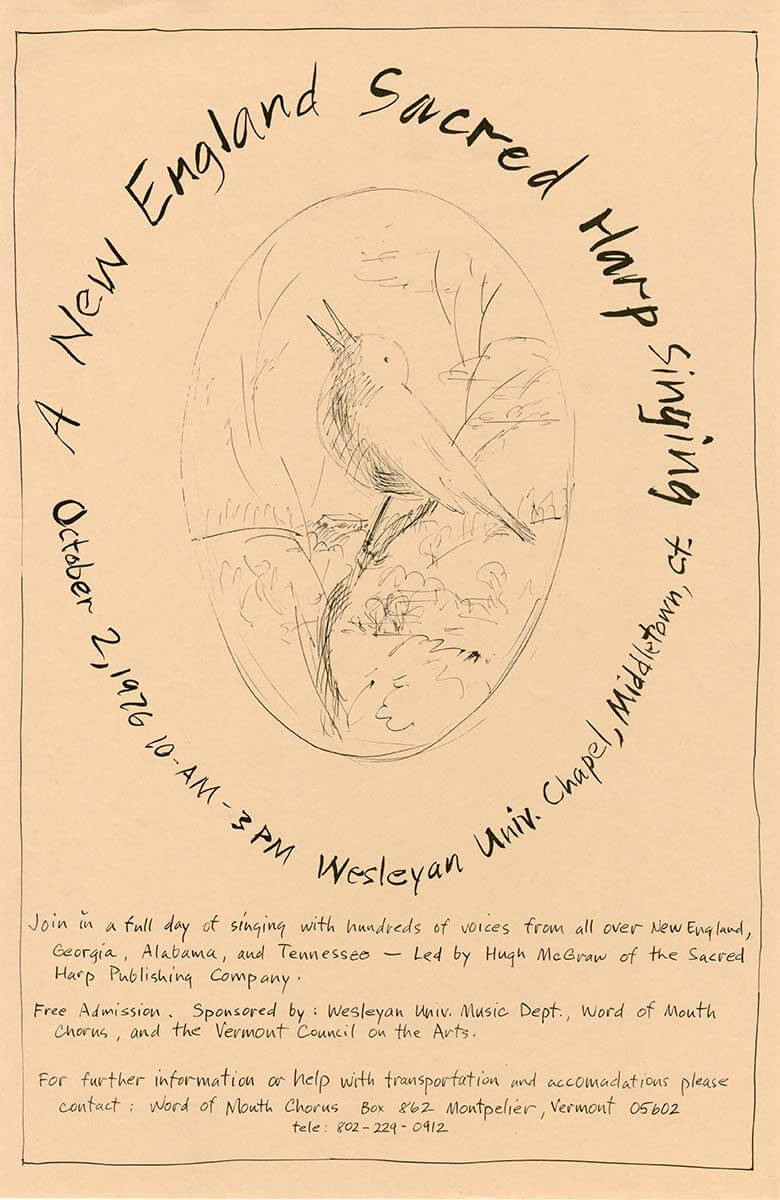

David Millstone calls English country dances, contras and squares, and innumerable “one-night stands.” He started contra dancing in New Hampshire in the early 1970s, when the repertoire featured many traditional dances; his articles about the history behind some of these dances appeared in Cracking Chestnuts: The Living Tradition of American Contra Dances, published by Country Dance and Song Society. As a videographer, he created documentaries about Bob McQuillen, Dudley Laufman and Ralph Sweet as well as a film about Shaker dance. David coordinates the Square Dance History Project, an online digital library. He served as CDSS President from 2012-2018.

Allison Thompson is an English country dance caller, musician and dance historian. Her most recent work is May Day Festivals in America, 1830 to the Present. Allison plays concertina, recorders and button accordion with the band Amarillis and has recorded several CDs with them. She is currently finalizing her study of dance tunes in the music collection of Jane Austen.

Introduction

Over the centuries, the related forms of country dance – Scottish, English, contras, and squares – have been enriched by the accretion of new steps, formations and figures, gradually adding in movements that dancers of previous generations would not recognize. Historically these additions were usually made by the invisible hand of Anonymous and it can be difficult to track the provenance of a figure. However, the swelling of new choreographies since the 1970s with their newly-invented figures printed in booklets has made this kind of investigation easier, and the proliferation both of publishing dances and engaging in social interactions on the internet has made it easier still.

One recent addition to the repertoire, the “dolphin hey,” has a well-documented provenance that begins in the Shetland Islands with stops in England, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the United States. Documenting the evolution and transmission of this figure has been a similarly international effort, with discussions on the Scottish strathspey discussion list and on the English country dance discussion list and further developed through email exchanges with choreographers and callers.

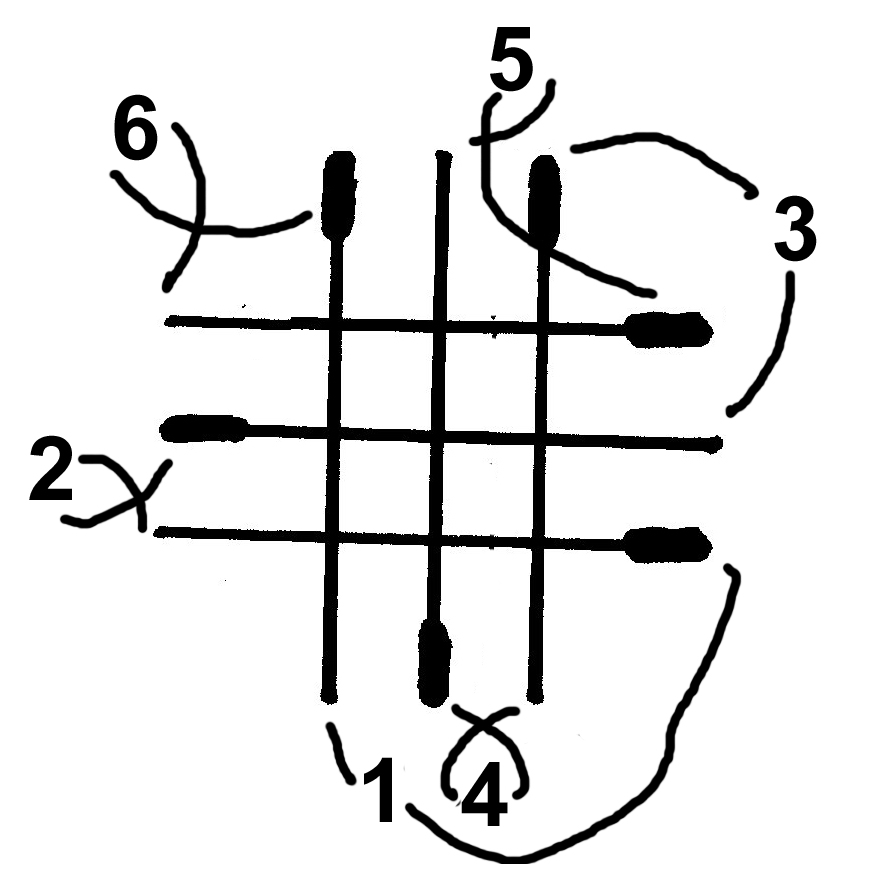

There are several variations of the dolphin hey, many of which are discussed below, but the form that is best known in English country dance circles in the United States is a hey/reel-of-three for four dancers, with one couple dancing as a unit, one behind the other. As that paired couple reaches the outer end of the hey, the trailing dancer turns the corner closely to take the lead in the hey and the original leading dancer becomes the follower. This moment of overtaking is the flirtatious, “fun” part of the hey. For a visual, imagine a pas de deux of silvery dolphins cutting through blue waters, the one in the rear leaping playfully ahead of the first only to be overtaken again.

It is important to note that there is not one “correct” dolphin hey/reel: there are many variations and approaches. As the twenty-three dances included in Appendix 2 show, the hey can be danced along the diagonal(s), across the set, up and down the set, around all four corners in a cloverleaf, as a morris hey, within a square set, and other variations. It can involve four dancers (the minimum) or more. It can be initiated with the active couple (the dolphins) cutting through the middle of the other dancers, or starting from the top of the hey – or other variations. It can involve a change of lead at both ends of the hey or at only one. It is a creative and entertaining figure!

The reel in which two or more of those people dancing are moving as a unit (historically with the man following his partner) seems to have originated in the island archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland, one hundred miles off the north-eastern tip of Scotland in the Norway Sea. The English dance historian and choreographer Pat Shuldham-Shaw (1917-1977) did research in the Shetlands in the late 1940s, collecting songs, fiddle tunes, and dances. He wrote:

The Shetland Reel is still a regular feature of Shetland weddings and is also occasionally danced at ordinary social dances. At a wedding the first set usually consists of the bride and best man, the best maid and bridegroom and the bride’s father and the bridegroom’s mother. . . . The reel is performed in a curious way. The set forms up as for a longways country dance with the middle couple “improper.” The reel is then started by the first woman casting down and the second woman casting up each followed by her partner. The third couple join in, the woman followed by her partner casting up. The figure-of-eight track is continued, each man closely following his partner and each couple acting as one unit, until everyone is back in their original place. [Shuldham-Shaw, Patrick. “Folk Music and Dance in Shetland.” Journal of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, vol. 5, no. 2, 1947, pp. 74-80. JSTOR.]

For their authoritative work, Traditional Dancing in Scotland, J. F. Flett and T. M. Flett interviewed several hundred elderly traditional dancers in the 1950s. They describe this reel as being danced as early as the 1880s (the edge of then-living memory), though it had dropped out of favor on various islands in the early part of the last century, shortly after World War I. They reached similar conclusions:

Until about 1900, the principal dances in Shetland were “Shetland Reels”. . . . A three-couple Reel of one form or another seems to have been known in every district of Shetland, but two-couple and four-couple Reels were more local in their distribution. . . . All these various Shetland Reels are true Reels, consisting of setting steps danced on the spot, alternated with a travelling figure. In all the three-couple and four-couple Reels the setting steps are performed with the dancers in two parallel lines, and in the travelling figures each couple moves as a single unit, with the lady leading and the man following immediately behind her; in the three-couple Reels the track followed by the dancers in the travelling figure is a figure “8”, and in the four-couple Reels it is a figure “8” with a third loop added. [Flett, J.F. and T.M. Traditional Dancing in Scotland. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1966. (UK edition, 1964)]

They describe a similar pattern for the Orkney Sixsome Reel. The Fletts did not give a name to this figure, nor, apparently, did the traditional dancers: it was just the proper way a reel was danced in their part of the world.

For a detailed description of the Shetland Reel and its place in traditional dance, we recommend an informative collection of videotaped interviews and dance footage, both contemporary and archival, created in 2017 by fiddler Maurice Henderson and his colleagues. The material illustrates the traditional stepping that is used in the first part of the dance and then the eponymous reel itself.

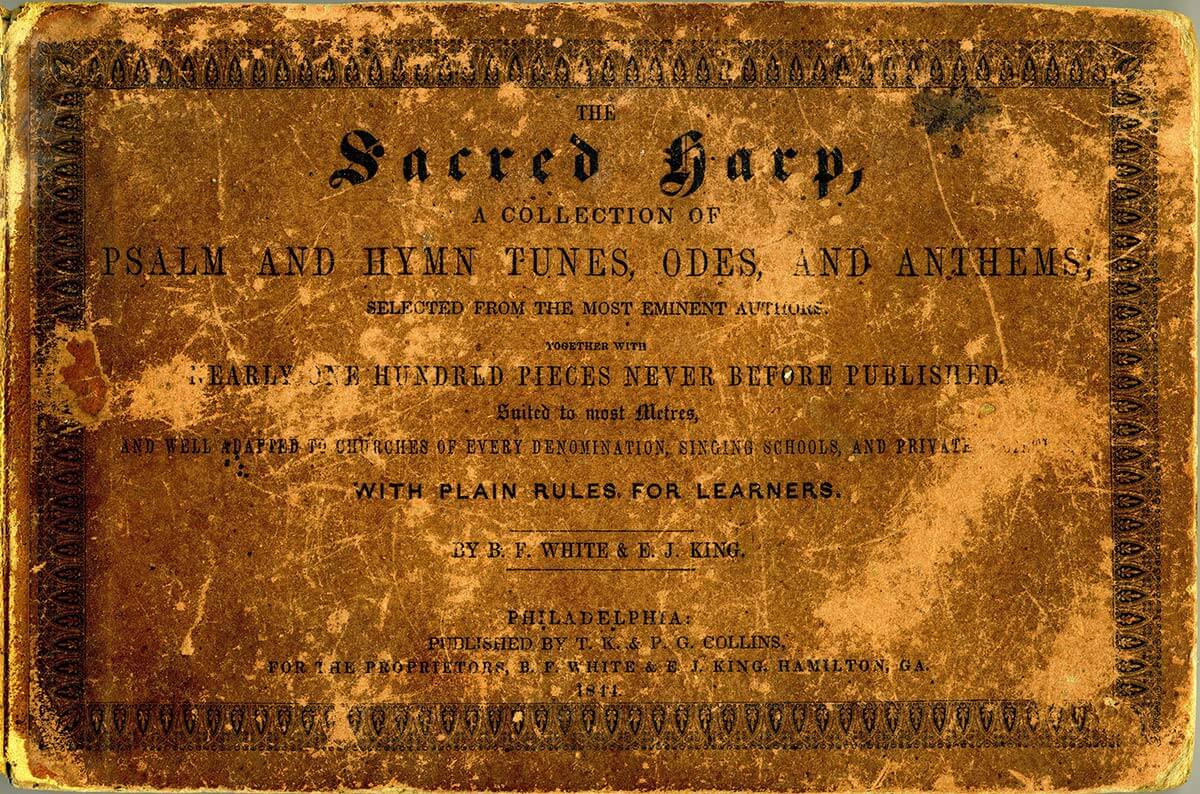

Scottish and English country dance choreographies developed on parallel tracks after World War II. In 1977, John Drewry [Drewry was a prolific creator of dances, with more than 800 to his credit. Though born in Leicestershire, England, it was when he began work at the University of Aberdeen that his passion for Scottish country dance developed fully. For decades, the Scottish country dance repertoire had been limited to a small number of figures and dances interpreted by Jean Milligan and her colleagues, in a manner similar in the English country dance world hewing closely to the dance interpretations of Cecil Sharp. Drewry and a few others began the process of expanding that repertoire through a series of new dances, new figures, and using older figures in unusual ways, just as Pat Shaw and subsequent choreographers did in the realm of English country dance (“Obituary: John Drewry, Scottish dance deviser and academic,” retrieved January 26, 2019). Those “few others” included James Cosh (devisor of Mairi’s Wedding) and Hugh Foss.

Foss, another Englishman, was married to a Scot and started Scottish country dancing in the 1930s. He was a member of the first Scottish Country Dance Society team to perform overseas:

As an Englishman he felt he was not entitled to wear a clan tartan so his kilt was the plain grey shepherd’s plaid. With grey beard, grey jacket and waistcoat, grey kilt and grey hose he was in appearance a grey man, but his personality and mind were quite the opposite. … In 1937, he was a member of the first SCDS team to dance overseas – at a Celtic Festival in Brittany, though English Hugh felt he was out of place representing Scotland at such an event. Nor did he accept everything emanating from Society Headquarters. He applied his own thought processes to each ruling and only followed it if it made sense to him. (“Hugh Foss,” reprinted from Scottish Country Dancer (No. 4), The Members’ Magazine of the RSCDS, Spring 2007, retrieved January 27, 2019.)

A brilliant mathematician, Foss was also an eminent codebreaker who achieved fame for breaking Japanese ciphers around the time of World War II. He is credited with encouraging Drewry to create more dances. (Wikipedia: “Hugh Foss,” retrieved January 27, 2019.)

] (1923-2014), the famous deviser of Scottish country dances, put the Shetland Reel figure into his composition, The St. Nicholas Boat. That same year, Pat Shaw incorporated that Shetland Reel figure in his dance, The American Husband or Her Man, and he later used it in his dance Buzzards Bay. In these dances, the three active couples in the sub-set dance a reel for three as units of two, the women in the lead. While Drewry did not name the figure, Shaw termed it a “Shetland reel.” However, Shaw’s dances incorporating this figure and the figure itself did not catch on in the United States at this time.

In 1981, Drewry published a new dance, Ferla Mor, in which he modified this reel by having only the leading couple dance as a unit: thus, the 1s, having moved below the 2s, begin a half reel of three with the first corners (i.e., 2M and 3W) and then the second corners (3M and 2W), the 1M man following behind his partner, with no change of lead.

Falcons turn to Dolphins

The next milestone in the evolution of the figure is pinned to another Scottish country dance, The Flight of the Falcon, written by Barry Priddey (GB) and published in Anniversary Tensome in 1992. US-based Scottish dance teacher Chris Ronald notes that, in this dance, Priddey “further developed the Ferla Mor pattern by having first couple change lead at each corner.” [Ronald, Chris. “A Brief Note on Shadow/Tandem/Dolphin/Falcon Reels,” 12 Scottish Country Dances, pp. 28-29. New York, 2009.] Priddey, a prolific Scottish dance choreographer who danced with the Sutton Coldfield branch of the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society (RSCDS) in the West Midlands of England, prefaced his description of The Flight of the Falcon thus: “[t]he merlin [Eds.: a type of falcon] flies close to the heather following every twist and turn of its quarry’s flight.” It was clearly the “following every turn” image that inspired Priddey’s innovation of the change of lead. Priddey did not name his figure either, merely describing it as follows: “1M, followed by his partner, begins to dance a diagonal reel of 3 with 1st corners. At the end of bar 10, having passed 3W by the right, 1M and 1W each turn right about to continue the reel with 1W leading, then at the end of bar 14, having passed 3W by the left, they each turn left about to complete the reel with 1M leading.”

The next year, in 1993, Barry Priddey published two Scottish country dances that took the concept of a paired reel even further in his dances The Capercaillie and Land of the Heather Hills (both published in his booklet, The Capercaillie). Both dances incorporate half-diagonal heys/reels for four that involve six dancers, four in pairs and two dancing independently. (That is, the 1s, dancing as a unit, and the 4s, dancing as a unit, dance four alternating half-reels of four with 2M and 3M and then 2W and 3W, with the paired units changing leads on the ends of the reel.)

From England, the Falcon dance traveled to New Zealand where Iain Simmonds, a Wellington teacher, introduced it at a weekend school in Auckland and at his Friday night advanced Scottish class. [Strathspey discussion list. “Tandem Reels.” July 8-August 8, 2011.] Rod Downey, another mathematician, used the figure for diagonal heys in his dance The Silkie. The figure also caught the attention of dance deviser Barry Skelton, who started creating his own dances using the figure, which he termed a tandem reel for three. On October 28, 1993, he wrote Dancing Dolphins. Two days later he devised Pelorus Jack, named after a famous dolphin that lived in Admiralty Bay between Wellington and Nelson, New Zealand. (See historical background in Appendix 1.) The dance makes a significant change from The Flight of the Falcon. The earlier dance has two complete diagonal heys, but Pelorus Jack includes four half-reels of three on the diagonal with a change of lead on every corner.

Skelton published The Dolphin Book in 1994. The eleven dances in the book – notably Dancing Dolphins, Opo, Orca, The Playful Porpoise, and Pelorus Jack – include the hey/reel for three with the 1s dancing as a unit and changing the lead on the ends of the heys. The author explained, “All the dances in this book have a type of tandem reel that people thought looked like Dolphins chasing each other through the waves. I was told that this one looks as if they were dancing.” With its 2000 re-publication in the RSCDS Book 41, Pelorus Jack became the best known of the Dolphin Book dances in Scottish country dance groups. In his book, Skelton did not refer to The Flight of the Falcon or to Brian Priddey.

However, Chris Ronald confirmed the direct link from Priddey to Skelton: “I did some research on “tandem/dolphin/falcon” reels and wrote it up in an annex to my book: 12 Scottish Country Dances. Shortly after completing that book, I met Barry Skelton in New Zealand, and he agreed that Barry Priddey was the originator of reels of three where 1st couple dance in tandem and change lead at each end of the reel.” [Ronald, Chris. Posted message to Strathspey.org, Aug. 8, 2011, retrieved January 26, 2019.]

Chris Ronald also notes that “[u]p to the time Pelorus Jack was published, in The Dolphin Book, no [Scottish dance] deviser had given a name to the concept whereby a dancer follows his partner in a reel of three. Barry Skelton chose the term ‘tandem’ to describe these reels, and the RSCDS used this terminology when publishing Pelorus Jack in Book 41 in 2000.” While Skelton may have used the word “tandem” in his printed directions, in a video in which he discusses the creation of this dance he suggests that his local dancers in 1994 already referred to the figure as the dolphin reel, at least informally. (This video interview is viewable here and contains footage of dancers performing Pelorus Jack.)

The Dolphins reach North America

By 1994 we have several very popular Scottish country dance devisers experimenting with different types of heys/reels in which at least one couple moves as a paired unit in which the version in which the 1s change lead is called an “alternating-lead tandem” or “dolphin” reel. But how did this figure migrate to the English dance repertoire? It seems to have had several distinct points – or perhaps more accurately, persons – of entry.

The Flight of the Falcon first traveled from England to New Zealand, thence to Australia. Rod Downey, a New Zealand SCD leader explained, “The RSCDS is a fairly monolithic organization and hence the books etc. get all round the world. Of course we can get many books here in New Zealand via the Branch bookshop. ECD seems not so organized. There is always a lot of trans-tasman [Eds.: i.e., across the Tasmanian Sea] movement so a lot of stuff between Australia and New Zealand” (Downey).

Elma See, an RSCDS examiner and dance leader in New South Wales, Australia, recalls that, “I think I first learned them with Iain Boyd at a New Zealand Summer School – Pelorus Jack perhaps” (See). She took the dance figure with her back to Australia and then was hired by the (Scottish) Teachers Association (Canada) to teach at a 1995 meeting in Ottawa, Canada. Among those present at the event was English and Scottish dance leader Bruce Hamilton. He writes:

Makes sense that Elma would have taught Dancing Dolphins then, since it would have been virtually brand new. I loved it, and taught it to the advanced SCD class at the San Francisco Branch’s Asilomar weekend the following November. Time passed, and the dances in the book entered the SCD repertoire. . . .

[Four years later,] I was the caller on Ken McFarland’s “English Country Dancing in English Manors” tour of England in 1999. We were in Dartington Hall on May 5, and I taught Dancing Dolphins then. I didn’t have to anglicize the dance very much, since it’s the standard 3-couple dance done in 4-couple sets. I may have turned it into a triple minor, or I may have left it in lines of 4 couples. At the time I said it was a shame that the ECD community hadn’t picked up on the Dolphin hey.

Mary Devlin, a member of that dancing tour, also remembers that moment:

I took his comment as a challenge and started imagining and visualizing as we traveled about by coach. I knew the dance was to a jig so I kept playing a generic jig in my head, and I knew that I wanted an ABBC structure with a musical punch at the beginning of C part. The dance itself came together fairly easily.

The group spent a couple of days at Halsway Manor and the dance had its first tryout in the hall on the main floor. [May 9, 1999] Everyone liked it a lot. One of our number – Lee Shepherd – suggested the title Halsway Manners and of course that was it. Once I knew the dance was right I had to find a tune and I didn’t know of any that did what I wanted. I asked Liz Donaldson to write one and she did a splendid job. I know it’s hard to write a tune “to order” (Devlin).

Halsway Manners is the first English country dance composed by an American choreographer to utilize the dolphin hey figure. Like Dancing Dolphins, Halsway Manners has the dolphin heys swimming up and down the sides of the dance. Commenting on the path that led to the composition of this dance, Bruce Hamilton said:

It is worth noting that a dance can be English in style without English parentage, Scottish style without Scottish parentage, and so forth. That fact is not new (it’s been true at least since Playford dropped [the word] “English” from “The [English] Dancing Master”), but it sometimes fades in a haze of patriotic enthusiasm.

Halsway Manners is a deliciously extreme example of this phenomenon. The core idea came from Barry Skelton in Auckland, New Zealand. Then Elma See, of New South Wales, Australia, taught Dancing Dolphins in Ottawa, Canada. I (a Californian) learned it from her there and later taught it in South Devon to Mary, who hails from Oregon. She presented her dance in Somerset, a woman from New York chose the name, and a woman from Maryland wrote the tune! It is an English dance, but because of its style rather than its parentage.

Two years after Halsway Manners was composed, Robin Hayden presented it at a program for experienced dancers for the Boston Centre CDS. Boston leader Helene Cornelius in turn taught the dance at Pinewoods Camp in 2003, which is where Christine Robb (“I’m not a Scottish dancer”) was introduced to the figure. Ten years later, Christine started work on a new dance that emerged in final form as Sapphire Sea in May of 2015. Unlike Halsway Manners, in this dance the dolphin heys go across the set rather than along the line.

Halsway Manners similarly caught the attention of St. Louis choreographer Bob Green. His 2012 dance, Waves of Grain, is set to a waltz written by his wife, fiddler Martha Edwards, and appeared in an issue of the CDSS News. He explains, “[Halsway Manners] was Martha’s favorite English dance to call, so it was a natural move to steal for a dance to her tune.” His choreography provides an opportunity for both couples in a duple minor set to dance the featured figure.

With the appearance in 2000 of Pelorus Jack in an official RSCDS publication, the tandem hey figure became more widely known in Scottish country dance groups. Following a different path, English- and Scottish-dance choreographers Brooke Friendly and Chris Sackett (US) have used the dolphin hey in several of their dances, notably in the very popular dance in 9/8 time, The Potter’s Wheel. Although the choreographers live in Oregon, as does Mary Devlin, Friendly notes, “When we created Potter’s Wheel (2009), we had not seen or done or known of Halsway Manners. We had done Dancing Dolphins and Playful Porpoise but hadn’t seen Barry’s book.” They did not give a name to the figure, merely describing its path.

Friendly adds that the first dance that they wrote with the dolphin hey was a Scottish country dance, Orcas Rising (Impropriety 2). “The tandem reel part of the dance was conceived in 1998 but the dance went through several iterations before it was finalized in 2006. We first encountered Mary Devlin’s dance Halsway Manners in 2003.” They have written other dances, Scottish or English in style, using the figure, and at the time using the “tandem reel” wording.

In much the same way as Friendly and Sackett came to the figure through Scottish country dance, so did Jenna Simpson, across the country in Williamsburg, Virginia: “I definitely knew dolphin heys from Scottish country dance, which I took up in 2009. It’s a pretty standard figure in our local SCD group’s repertoire. Before I wrote ‘Under the Influence,’ the only ECD in which I had encountered the figure was Potter’s Wheel. (I’m pretty sure I learned it in Scottish before I first did Potter’s Wheel.)”

That same year, Alan Winston, in California, created his dance, Movement Afoot, set to a fiery waltz by Larry Unger. Winston had encountered Halsway Manners before this, “but it didn’t make that much of an impact on me. During my year and a half of Scottish dancing before I blew my foot out, I encountered both Flight of the Falcon and Pelorus Jack, which did make an impact on me.” He did not encounter Potter’s Wheel (2009) until after writing Movement Afoot (2013): “I remember when I did hit Potter’s Wheel I noticed that something I’d used in an ‘English’ dance was now in use elsewhere.” His dance starts with a dramatic movement, as dancers set forward to a standing (and not retreating) partner. The lead-in to the dolphin hey also begins in an unusual fashion as well, with active men wheeling to their left to pass left shoulder with the neighboring man.

In most cases today, a choreographer starts with a piece of music and works from there. The norm in English country dancing is for each dance to be set to its own tune, though this was far from standard practice several hundred years ago. A new tune, Tom Kruskal’s, was composed by Amelia Mason and Emily Troll to honor that Boston musician and morris dance leader, a 2010 recipient of the CDSS Lifetime Contribution Award. The tune spread widely with performances and a recording by the popular contra dance band Elixir, and Christine Robb and Jenna Simpson each contacted the tune’s authors in 2013 with a request to use the melody for a dance. Each independently created a dance: Sapphire Sea, a longways duple minor by Robb, and Under the Influence, a four-couple set dance by Simpson. Interestingly, both Simpson and Robb used a form of the dolphin hey in their dances as the figure for the start of the B1 music, in which the tune rises, affirming the adage, “The music tells you what to do.”

Simpson’s Scottish dance background shows in multiple ways. She uses Petronella turns – Petronella is the first dance in the first volume of RSCDS’ publications. Her dance specifies a skip-change step at one point. Finally, her directions clearly draw on Scottish sources, as do those of Chris and Brooke: “The figure in B1 is a variation on the ‘alternating tandem reels’ (heys) (also known as ‘dolphin’ reels) found in some Scottish country dances.” Consciously or not, the orientation of the active dancers, where one is not directly behind the other, also harkens back to the position of dancers in Skelton’s original composition, Dancing Dolphins.

The Dolphins return to England

In the last section, we looked at the several routes by which dolphin heys became included in English country dances written in the United States. With an ocean separating us and only a small number of callers working on both sides of the Atlantic, there are many choreographers in England whose work is unknown to most American dancers.

A vital transmission link for the dolphin figure in England was Ron Coxall, an English caller and choreographer. (Among his better-known dances in North America is Turn of the Tide [1999]. He has published extensively, and his 1991 dance The Short and the Tall uses a serpentine figure that inspired a contra dance hit by William Watson, The Devil’s Backbone.) For thirty years, Coxall has had a routine for escaping English winters: “I have been visiting Adelaide in South Australia since 1988 and as I like to dance have supplemented English Country Dance with Scottish while there” (Coxall).The preface to his 2005 dance booklet, Walls, notes: “l first met Dolphin Reels and Barry Skelton’s book The Dolphin Book when in Australia in February 1996 and wondered why Scottish Country Dancers should have them all to themselves. Barry Skelton is a prolific composer of dances from Auckland, New Zealand and these following dances are by him but I have changed them slightly to conform to English country dance style.”

Coxall returned to England in 1996 and led a well-received session of dolphin dances at the Eastbourne Festival. He corresponded with Skelton in 2003 and received permission to include versions of some of Skelton’s dolphin dances. Coxall’s book Walls contains five such adaptations: Orca, Opo, Dancing Dolphins, Sounding the Deep, and Pelorus Jack.

Here it is useful to note that the standard formation for a Scottish country dance is four couples in a longways set, with the 1s generally (but not always – some dances like Capercaillie involve all four couples at once) dancing only with couples 2 and 3, then progressing down one place to dance with couples 3 and 4, then dropping to the foot of the set: this is called “twice and to the bottom” in RSCDS terminology. In some dances, the 1s interact mainly with the 2s, with the 3s acting as posts and the 4s as neutrals. When Ron Coxall adapted Skelton’s Scottish dances, therefore, his principal change was to convert the dances Orca and Opo (which are of the latter type) to duple minor longways formation; Sounding the Deep as a four couple longways; and Pelorus Jack as a three couple longways. Coxall also specifically called the distinctive figure a “dolphin reel,” and it is implied in his introductory comments to Walls that that was how it was referred to in Australia when he met it in 1996. He described the dolphin reel thus:

A Dolphin Reel is danced by a couple acting as a unit and retaining the same orientation to each other throughout the reel. If the lady leads out of the reel, on the way back the man will lead. I sometimes call this a shadow reel: when dancing towards the light the shadow is behind but when dancing away the shadow is in front. If the reel is across the set then an imaginary line joining the couple should always be parallel to a line across the set. The couple’s shoulders should also be parallel to each other.

For example, Skelton’s Orca was a 24-bar dance, arranged as a three-couple dance within a four-couple set. Coxall adapted the dance to a longways set, modified the opening and kept the dolphin reel in the same A2 section. He modified B1, and keeping the dance more in line with the common ECD setting of a 32-bar dance, added a double-figure eight.

There may be one example of dolphins reaching English country dance in England before Coxall. Chris Turner (UK) writes: “I was using that figure in my choreography as early as 1995. Might have assimilated it at Eastbourne but think it was earlier. I remember Ron Coxall at Eastbourne that year. Faint memory of teaching heys in general at a class and Scottish interloper telling me about dolphins and New Zealand. This was very possibly where I learnt about it and it was certainly before 1996.” Turner notes that his dance, Jack’s Dolphin, “started life as a square version of Jack’s Maggot, and goes well to that tune.”

With Coxall’s presentation at the Eastbourne festival and the publication of Walls, the dolphins took flight, as it were. Trevor Monson (UK) comments, “After that dolphin reels started appearing in modern English style dances – even mine!” He notes that after 1996, some English dancers in England were exposed to the dolphin hey in dances that they thought of as purely English country dances. Monson’s dance, Dolphins in the Sound, though created without knowledge of the earlier Pelorus Jack, includes dolphin half-heys on the diagonal. It follows an ABBC pattern for its perky tune, and has a considerably different feel than its Scottish cousin.

Dolphins appear in new forms

Another choreographer inspired by Ron Coxall was Sue Carter: “[He] had just returned from New Zealand where he had danced Pelorus Jack, Dancing Dolphins, etc., so he called them all at that weekend. The figure was very new at the time. English choreographers know a good, interesting figure when they see one and write a dance with one in. I was no exception!”

Her composition, Golden Dolphins, illustrates the common practice of using a figure in ever-more-complex ways. Priddey’s original The Flight of the Falcon took the Shetland Reel figure, adapted it so that just one couple was acting as a unit, added the overtaking feature at either end of the hey, and set the hey on a diagonal. Carter adds yet another new variation: the dance is for five couples and her dolphin hey for three involves five dancers, not four: two end pairs of same-sex neighbors each act as a unit to dance the hey with the middle individuals in each line. As an additional wrinkle, it’s a morris dolphin hey.

Robert Sibthorpe (UK) learned the dolphin hey in Pelorus Jack in 2002, two years after the RSCDS published it, at a Scottish Country Dance Club in Leigh-on-Sea, Essex. He incorporated that move into another five-couple dance, Windhover.

As we have seen, the dolphin figure first appeared in three- and four-couple longways set dances. It then moved into four-couple squares and five-couple longways sets. Madeleine Smith first encountered dolphin heys from the calling of Robert Sibthorpe. Her 2008 composition, A Dolphin in Broadstairs, created for a workshop at Broadstairs Folk Week, showcased the figure in yet another formation, a square with an additional couple in the center. Smith based her dance on The Fivepenny Piece (author unknown) and on Chris Turner’s Jack’s Dolphin. Note that in this dance the overtaking only occurs at one end of the hey; in our discussion of terminology that appears towards the end of this article, this could be classified as a “single switchback reel.” Thus, in B1, the middle couple starts the hey by passing right shoulder with the second man. The middle lady overtakes her partner going around the first turn and she remains in the lead around the second end and crossing the set to start the second hey, starting left shoulder with the fourth lady.

As we have seen, choreographers have placed the dolphin hey figure in a variety of formations. They have also started creating variants in the figure itself. Belgian choreographer Philippe Callens’s dance Somerset Square includes what he terms a dolphin gypsy: “The movement is inspired by what English morris dance teacher Laurel Swift had dancers do during her ‘Cotswold Morris: New Perspectives’ class, [at] English-American Week, Pinewoods, August 2007.” In Swift’s whole gyp, dancers moved in pairs, starting with one person in front and the other behind. Callens notes, “Since I used only three-quarters of a gyp in my dance, the person behind, as in a dolphin hey, would become the leader.” Swift herself did not use the term “dolphin” in her teaching – “I wasn’t familiar with the dolphin hey at the time of those Pinewoods morris classes, as I hadn’t done any English or Scottish country dancing before coming to Pinewoods (I’d done lots of ceilidhs, but hadn’t come across the move in that, at least not with that terminology)” – but Callens was familiar with the dolphin terminology and selected it for his figure.

The prolific English choreographer Colin Wallace – more than 1,500 dances to his credit – is perhaps best known in the United States for his dance The Zither Man. Many of his dances are very complex creations and it is not surprising that he, too, has written more than a dozen dances with dolphin figures, starting in 2008. One such composition, Cetacean Creation, was written in 2009, the same year as Somerset Square. In addition to a complicated lead into half dolphin heys on the side, Wallace’s dance also includes a half dolphin gypsy.

From Scottish to English to Contras

Once introduced into a dance community, figures are frequently adapted on the dance floor. For example, in the contra dance world in the United States, standard heys for four became established in the 1980s. As dancers became more familiar with the movement, they started improvising and discovered that they could change the figure by doing a push-back or ricochet with another dancer in the center to change their order. Whether following the lead of the dancers or coming up with a similar idea independently, choreographers started to specify that variation in new compositions. Thus, in the contra world, that led to Adam Carlson’s 1999 dance, The Queen Bee, the first with a push-back hey. In a similar manner, GB choreographer Rob Sibthorpe’s dance Dolphinarium introduces a “dolphin swap” adaptation to let two dancers change places mid-stream.

English caller Rhodri Davies explains the background of his contra dance, Just Skylarking: “It was first danced on 27th May 2007 in the ‘Zesty Contra’ dance at Chippenham Festival, which I was calling with the band Skylark. . . . [The dolphin hey] had appeared on the English country dance scene here and this was a conscious attempt to put a dolphin hey into a contra dance. My memory of it is it just appeared in several dances around the same time, and I suspect like a lot of the authors of those dances, having seen it, I thought it was neat and wanted to use it.”

Talk about borrowed figures! Not only does this contra dance Just Skylarking incorporate the dolphin hey (from Scottish country dance via English country dance), it also includes a Petronella twirl (a figure with Scottish origins, and now an established part of the contemporary contra vocabulary) and a 50-year-old figure from modern square dance, the Dixie Twirl, created in 1959 by Roy Watkins. [Ceder, Vic. Definitions of Old Calls.]

The process of borrowing and adapting figures continues. Nearly ten years later and across an ocean, American contra caller and choreographer Luke Donforth had his first encounter with the dolphin hey: “I was at the ECD at the Memorial Day Dawn Dance (May 29) in 2016 [in Brattleboro, Vermont]. Nikki Herbst called a dance, Orca, with a Dolphin hey. It was such fun I decided to write contra dances with it (when I was lying awake in bed, and should have been resting before calling the 3 -7 AM shift.) I eventually came up with five, of which Kinematic Dolphin Vorticity (which borrows the A1 gate figure from Carol Ormand’s Kinematic Vorticity) is my favorite.”

Within two weeks of that event, Donforth initiated a conversation on the Shared Weight callers’ listserv to share his enthusiasm for this figure. His post drew immediate responses from New York, New Zealand, San Francisco, St. Louis, California, and England. By late January, 2019, the Caller’s Box online database listed 27 contras with a dolphin hey.

What’s in a name?

For two decades, unresolved nomenclature troubled dance choreographers and dancers (and dance editors!): there were too many names for this figure and its relatives. In the beginning, the Scottish country dance world saw lively discussion around the use of the term “tandem reel.” In Dancing Dolphins, Skelton has very specific wording: “First couple in tandem, dance a right shoulder reel of three with second and third lady.” However, the detailed instructions for that dance have that active couple standing side by side, as if they were twins in a perambulator, to begin the reels and they are asked to remain parallel to the set throughout the reels. (Unfortunately, the various online videos of the dance do not show this detail.) Of the remaining Dolphin Book dances, some have the active couple starting side by side to each other and some start with one dancer behind the other, though no other dance directions specify remaining parallel to the set. Skelton uses “tandem” to refer to all of these possibilities, a source of some consternation within the RSCDS community, where precise definition of terms plays a strong role.

Various alternative wordings have been offered: falcon reels, shadow reels, swap-over reels, overtaking reels, and even double switchback tandem reels, which is far too wordy for common usage. (However, the “double switchback” wording is helpful because it illustrates that the figure can involve changing the lead at one or both ends of the hey.) For the first fifteen or twenty years, the various nomenclature could be summarized as follows:

|

Reel/hey for six people dancing as three paired units |

|

|

Reel/hey for four or more people, at least two of whom dance as a unit with no change in lead |

|

|

Hey for four or more people, at least one couple dancing as a unit, changing leads on the ends |

|

There is widespread agreement now that the “tandem reel” designation is properly applied to dances such as the Shetland Reel or other dances where one dancer stays in front the entire time through the figure; this conforms to the widespread understanding of the word “tandem” as in “tandem bicycle.” As many have noted, cyclists don’t get up to change position going around each turn! Skelton’s Pelorus Jack was published by the RSCDS in Book 41 in 2000 using the phrase “tandem reel,” and many lamented that choice of words. New Zealand caller Iain Boyd put it bluntly: “On this occasion the RSCDS got it wrong. We have to live with it, but, we do not have to agree with them.” [Boyd, Iain. Posted message to Strathspey.org, July 8, 2011, retrieved January 26, 2019.]

The official RSCDS term now for the figure is “alternating tandem reel,” [Scottish Country Dancing Dictionary. “Alternating Tandem Reel of Three,” retrieved January 29, 2019.] though “dolphin reel” is also commonly used. English country dance groups use either “dolphin hey” (USA) or “dolphin reel” (England), and that wording has also carried into the contra worlds in those two communities. Faced with a multiplicity of options, one caller noted simply that he uses the term that will be familiar to most of the dancers at a particular event.

After a lengthy discussion of terms on the Strathspey listserv, Tim Wilson commented:

I have to laugh though. We’ve got “falcon” reels and “dolphin” reels which must mean that most of our reels are neither fish nor fowl. (And, yes, I am aware that a dolphin is not a fish.) Perhaps we can add “haring reels” – for when at least one dancer goes off on their own [Eds: wandering off alone is called “haring off” in England] – or better yet “red herring reels” when one dancer follows a cue that sends him or her in the wrong direction. [Wilson, Tim. “Dolphin reels revisited,” June 28, 2006.]

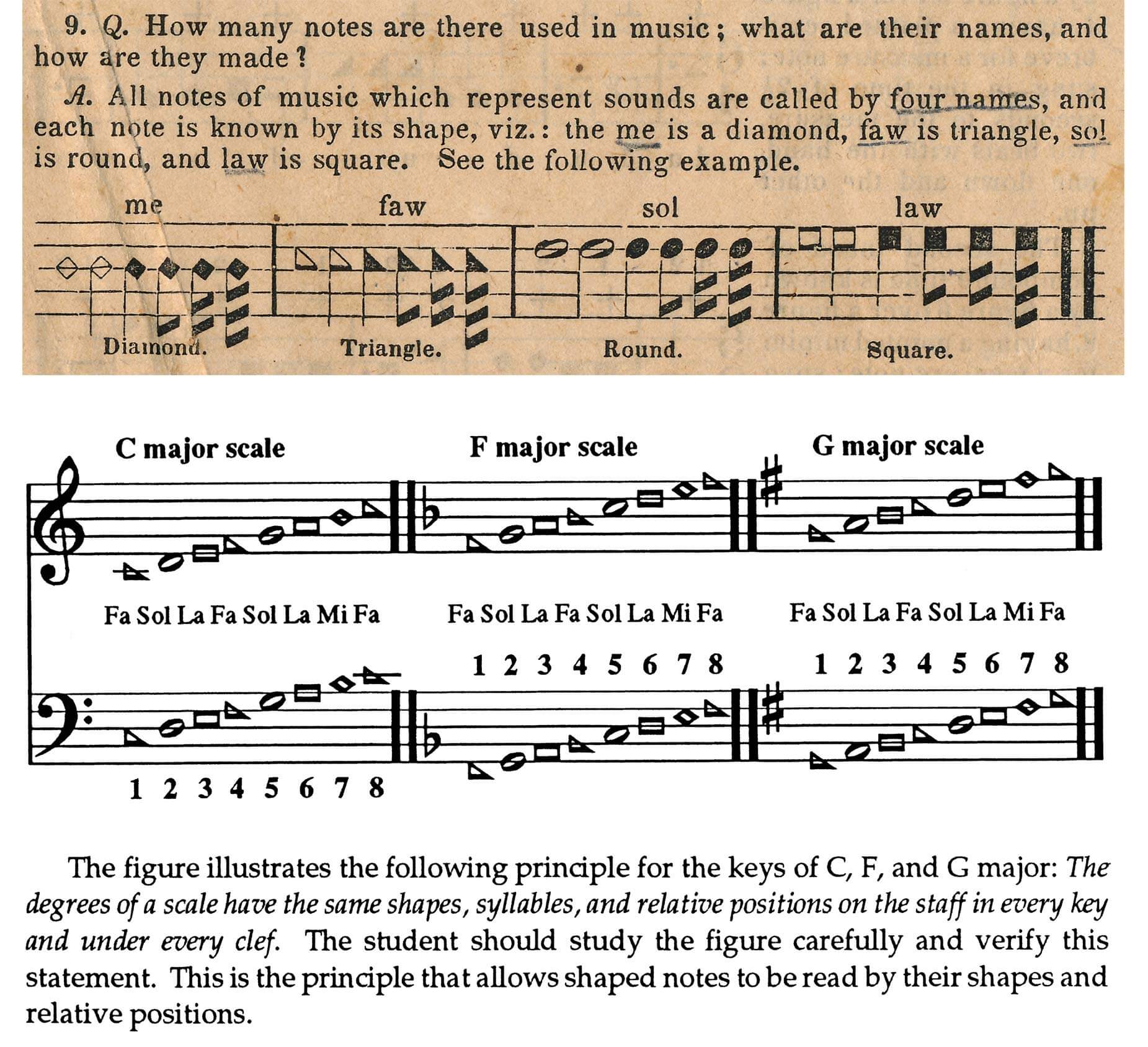

Dance instructors know that one of the challenges faced by new dancers is learning what all these specialized terms mean in terms of actual movement. Why must we agree on dance jargon? Why not just tell the dancers what to do?

Country dances in all styles make widespread use of short names to cover a series of multiple connected moves. A lengthy description can be useful for explaining an unfamiliar move, especially a complex series of discrete movements, but having a handy figure name is vital for dances that are prompted. In the contra world, for example, “ladies chain,” a modification of the older “ladies change,” is simply a short form of saying, “Two opposite ladies give right hands to each other to change sides, then with the assistance of the opposite gent, join left hands with him and do a courtesy turn halfway around to face back across the set.” Try calling that out in the middle of a lively contra!

More recently created figures in English country dance follow a similar pattern: a “Chevron” is shorthand for one set of corner dancers trading places on the diagonal, then backing straight back across the set, while the other two dancers wait and then cast to the spot vacated by their neighbor. Even staple figures of the ECD repertoire can be thought of as shorthand: a “hey for three” is an efficient way of describing, for example, the opening move of Jack’s Maggot: “The first man passes right shoulder with the second woman. As he loops to the right, she passes left shoulder with the first woman who in turn passes right shoulder with the first man moving up the set while the second woman loops to her left. . .” and so on. Traditional square dance has “Grand Square” as shorthand for a 16-count figure, usually followed by the equally short command, “Reverse!” to cue another 16 beats of movement. The simple phrase, “Teacup chain!” initiates a full 32-beat figure. Especially as one moves through the different programs in modern square dance – Mainstream, Plus, Advanced, and Challenge – a named figure incorporates ever-more-complex series of individual movements, with calls such as Load the Boat, Relay the Deucy, Ping Pong Circulate, Chain Reaction, Recycle, Scoot and Dodge, Percolate, Shazam, Lateral Substitute, and literally hundreds more.

Summary

As the dolphin hey figure has gained in popularity, it has begun to lose its back stories – both to the connections to specific Scottish dances and choreographers and to the question of why the figure is associated with dolphins, and which dolphins in particular. (See Appendix 1 for the rest of that story.) Bruce Hamilton writes that: “[i]nterestingly, I first encountered Skelton’s dance Opo in February 2013 in Somerset, England, as an English country dance in duple minor formation! No one there knew where the dolphin hey came from.”

The dolphin hey/reel originated as a simple hey for three couples dancing as paired units in the Orkney and Shetland Islands at least as early as 1880. In 1977, John Drewry introduced the figure into Scottish country dances, while Pat Shaw experimented with incorporating it into English country dances – the latter did not become popular. Drewry and Scottish country dance writers Barry Priddey and Barry Skelton continued to play with the form of the hey/reel, with Priddey adding the changing lead in 1993 and Skelton giving a successful name to the figure and popularizing it in his Dolphin Dances book of 1994. The figure was encountered by individuals who danced in English, Scottish and American contra communities and in various ways and various times introduced it into their repertoires. As more dancers and choreographers encountered the dolphin hey it is certain that more dances will be devised with this intriguing and popular figure. But the value of this tracing of the evolution and dissemination of the dolphin hey lies in its providing proof that, as we enter the second hundred years of the what is called “the folk revival,” the worlds of English, Scottish and American country dance remain vibrant, innovative, and open to fruitful cross-pollination.

Appendix 1 – About the Dolphins Pelorus Jack and Opo

Pelorus Jack was a famous dolphin that piloted ships in Cook Strait, New Zealand between 1888 and 1912. This channel between the North and South Islands is narrow and dangerous, but, according to legend, no shipwrecks occurred when Jack was present. Many sailors and travelers saw Pelorus Jack and ships would even wait for his escort. Jack, whose sex was never determined, has been identified as a Russo’s dolphin, Grampus griseus, an uncommon species in New Zealand waters. In 1904, someone on board the SS Penguin tried to shoot Pelorus Jack with a rifle; Jack was subsequently protected by an Order of Parliament under the Sea Fisheries Act on September 26, 1904, making him, it is believed, the first sea animal in the world to be so protected. Jack continued to guide ships through the straits but, according to folklore, he never helped the SS Penguin again, and she was subsequently wrecked in Cook Strait in 1909. Pelorus Jack was last seen in April of 1912. There are rumors that he disappeared after Norwegian whalers went through the straits, but it is considered more probable that he died of natural causes. “Pelorus” is the name of a bay or sound on the tip of the South Island, but despite his name Jack (or Jill) apparently never visited the bay. In marine navigation a pelorus is a type of “dumb compass” that permits observation of relative bearings; the instrument was named after Hannibal’s pilot, ca. 203 BC.

Opo was a bottlenose dolphin who became famous throughout New Zealand during the summers of 1955-56 for playing with the children of the small town of Opononi on the northern tip of the north island. She was originally named Opononi Jack, based on Pelorus Jack’s fame, since she was presumed to be male. Opo would play with the children and perform stunts and she became a considerable celebrity. The town requested official protection for Opo; this was made law on March 8, 1956, but the next day she was found dead in a rock crevice. She had either become stranded while fishing or was killed by fishermen fishing with dynamite. Her death made national news, and she was buried with full Maori honors near the Memorial Hall.

Footage of both Pelorus Jack and Opo, including the song “Opo the Crazy Dolphin” – the word “crazy” here used like “wicked good” or “really neat” – is viewable here.

Appendix 2: A Pod of Dolphin Dances

This is not intended to be a complete collection of all dances that feature dolphin heys/reels, but a selection of those mentioned in the context of the article. While we hope that these edited versions of the dances are useful to you, we hope that you will turn as well to the originals for more background, for the tunes, or for the choreographers’ original wording.

Note 1: Many of these dances have video links: if the title is in blue, click on that to view the video. Many of the Scottish dances have links to “mini-cribs,” and some of the English country or contra dances similarly link to choreographers’ websites where directions and tunes can be found. These links are shown just above the beginning of the directions to a specific dance.

Note 2: Some of these dances involve dancing with “corners.” To identify their corners, 1s, standing below the 2s, point both hands at each other, then slightly widen the hands to point to people across the set, on either side of their partners. As the active dancers look across the set from this position, their first corner is on the right diagonal, the second corner is on the left diagonal, their third corner is immediately to their left on their side of the dance, and their fourth corner is to their immediate right.

Note 3: For the “tandem-ness” of the paired unit and the change in lead to be appreciated properly (whether as dancers or spectators), dolphin heys/reels require 1) as much space as possible, and 2) that the paired unit follow each other closely, which can be challenging if dancing with a skip change of step, and finally and most importantly 3) engaging, or “covering” as the Scottish dancers term it, with one’s partner at the change in lead. This covering can be seen very clearly in the video of Pelorus Jack. Without these three considerations, the hey looks like a muddle and the playfulness of the dolphins is suppressed.

The Capercaillie

Barry Priddey

The Capercaillie Book of Scottish Country Dances, 1993

Scottish country dance

Longways for 4 couples: 3s and 4s improper

Tune: 32 bar jigs, 8 times through

Mini-crib

| A1 | 1-4 | 1s and 4s set and cast into middle places: on bars 3 and 4, 2s and 3s step up or down to the ends and become “corners” | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-8 | 1s and 4s turn partners by the left 1½ and end with 1W facing her first corner (2M) with her partner behind her and 4W facing the 3M, with her partner behind her. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

(First half-reel, women in the lead) |

(Second half-reel, men in the lead) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| A2 | 1-4 | With 1s and 4s dancing as unit, half-dolphin reel of 4 on the first corner diagonal, starting by passing right shoulder with the first corner dancers; dolphin couples pass by the left to face second corners (2W and 3W) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-8 | Half-dolphin reel; dolphins pass by the left to face 3rd corners | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| B1 | 1-4 | Half-dolphin reel; dolphins pass by the left to face 4th corners | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-8 | Half-dolphin reel; at the end, as active couples are passing left shoulder in the center, 1W and 4W pull back their right shoulders to face their partners. (End 2 – 4 – 1 – 3, with 4s and 3s still improper) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| B2 | 1-2 | 1s and 4s turn partners by the right hand halfway and retain hands . . . | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3-4 | . . . to join the other couple for right hands across halfway | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5-8 | 2s and 4s left hands across while 1s and 3s the same. (End 2 – 4 – 1 – 3, with 1s and 3s improper) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

The capercaillie, the national bird of Scotland, is the largest of the grouse species with a distinctive coloration and a prominent, fan-shaped tail.

Cetacean Creation

Colin Wallace, 2009

English country dance

Longways for 4 couples

Suggested tune: Temperance Reel (4x)

| A1 | 1-2 | All set. |

| 3-8 | First long corners half-gypsy right with middle neighbors (who cast right into this), then follow (as trailers in units) next middle neighbors (who have meanwhile changed places by the right shoulder on the left diagonal to face out) into half Dolphin Heys along their own side but finish in middle of other side (by crossing in and over through the end). (Men’s side: M4, M3, W4, M2. Women’s side: W3, M1, W2, W1.) |

|

| A2 | 1-8 | Repeat A1:1-8. (2-4-1-3, middles improper.) |

| B1 | 1-4 | Middle 4 (still as units) half Dolphin Gypsy L to opposite places (i.e. file counterclockwise halfway, changing leaders when all on center-line), while ends lead away and single-cast back to face partner. (2-4-1-3, all proper.) |

| 5-8 | Partners back-to-back left shoulder, all to face left along own side. | |

| B2 | 1-4 | All 8 circle left halfway. |

| 5-8 | Partners cross by the right shoulder, “Hole in the Wall” style | |

| End 3 – 1 – 4 – 2 | ||

Author’s dance notes: “After the setting in each A phrase, the second long corners should turn single left to flow into the Dolphin Hey. Not the normal turn single right after setting R and L, granted, but simple enough if you concentrate slightly more than normal on style and on getting exactly half your weight on each foot after the set (my phrase for this, and already a dance-title, is “Bifurcate Your Burden”). One can then turn either way with equal ease.

“Title: when one “Dolphin” (A1:3-8) is followed by another (A2:3-8), a little “Dolphin” (B1:1-4) may be created.”

Dancing Dolphins

Barry Skelton, 1993

Published in The Dolphin Book, 1994

Scottish country dance

Longways for 4 couples, 3 couples active

Tune: 32 bar jigs, 8 times through (Barry suggested The Lantern of the North)

Mini-crib

| A1 | 1-4 | Giving right hand in passing, 1s cross and go below, 2s stepping up on bars 3 and 4 |

| 5-8 | 1s turn by the left 1 and ¼ to end facing the women’s side, 1W to the right of 1M | |

| A2 | 1-8 | 1s dancing as a unit: dolphin reel for 3 on the women’s side (1W begins bypassing 3W by the right shoulder); 1s end on the men’s side of the dance |

| B1 | 1-8 | 1s dancing as a unit: a dolphin reel for 3 (1W begins by passing 3M by the left shoulder); end in promenade hold facing the women’s side |

| B2 | 1-6 | With hands joined, 1s dance out the women’s side, down around the 3W and up the middle to the top of the set |

| 7-8 | 1s drop hands and cast to second place |

A Dolphin in Broadstairs

Madeleine Smith, 2006

English country dance

4 couples in a square with a fifth couple in the center

Tune: 48 bar tune; Madeleine likes Dingle Regatta

| 3C | ||

| 4C | 5C | 2C |

| 1C | ||

| TOP |

| A1 | 1-8 | Partners balance and swing, ending with middle couple facing up |

| A2 | 1-4 | 5s and 1s right hands across |

| 5-8 | 5s and 3s left hands across, ending with the 5M, with 5W behind him, facing the 2s | |

| B1 | 1-8 | With the 5s dancing as a unit, the 5s and 2s dance a dolphin hey for 3, starting with 5M passing 2M by the right. The actives change places going around 2M, but then 5W stays in the lead going around him at the other end of the hey. End with middle couple approaching the 4s, with 5W in the lead |

| B2 | 1-8 | With the 5s dancing as a unit, the 5s and 4s dolphin hey for 3 with 5W passing 4W by the left to begin. Again, the 5s change roles only once, so they end with the gent in the lead back in the center of the set facing the 1s |

| C1 | 1-4 | 5s and 1s set right and left and swap places with the 5s making an arch and the 1s diving under, and California twirl, 1s, now in the middle, turning to face the 2s |

| 5-8 | 1s and 2s set right and left and dive and California twirl to swap places | |

| C2 | 1-4 | 2s (now in the middle) and 3s set and dive and twirl |

| 5-8 | 3s (now in the middle) and 4s set and dive and twirl. |

The progression moves CCW, with the former 4th couple ending as 5s in the center of the set and facing the former 5th couple who are now 1s.

Dolphinarium

Robert Sibthorpe, 2007

Nineteen to the Dozen

English country dance.

Square set

Tunes: American style 48 bar reels, 4 times through

| A1 | 1-4 | Head couples forward and back | |||||||||

| 5-8 | Heads do-si-do opposites | ||||||||||

| A2, B1 | [Star The Route] Head couples star right 3/4 (6 steps), star left all the way with nearer Side couple (8 steps, going across the phrase of music); head couples star right halfway in the center (4 steps); star left all the way with the other side couple (8 steps); heads star right 3/4 in the center (6 steps). Heads end facing in the direction they are moving, woman behind her partner: viz, from original position, 1C faces the side couple on their left while 3C faces 2C. | ||||||||||

| B2 | 1-16 | [Dolphin Swap] Head couples (men leading) go through Side couple on their left to start the “dolphin swap” figure. At its conclusion, head women have changed places with the side women who started on their left. | |||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| C1 | 1-4 | New Side women chain halfway (all now with original Corners) | |||||||||

| 5-8 | Promenade … | ||||||||||

| C2 | 1-4 | … to men’s home positions (women have moved one place clockwise in the set) | |||||||||

| 5-8 | Partners swing. |

Sequence: Heads lead twice, Sides lead twice.

[Eds: In the video, the dancers skip the final ¾ star in the center before the Dolphin Swap.]Dolphin Swap

This is a standard dolphin reel with three differences.

| ONE: | When the two women meet for the first time (this is the third pass in the reel), they quickly do a half-turn with the right hand and take each other’s place in the reel, pulling by. |

| TWO: | After the fourth pass, the original Side woman, followed by the Head man, curls round into Head place. |

| THREE: | Also after the fourth pass, the Side man stays on the right-hand track to turn the original Head woman with the left hand (1½ turns or ½ turn – you choose) and guide her into the next figure. |

Dolphins in the Sound (Sound of Iona)

Trevor Monson, 2009

One Candle – and other dances

English country dance

Longways for 3 couples (See note)

Tune: Jordan’s Shore by Elvyn Blomfield

Tune is played ABBC.

| A | 1-2 | 1s face down and pass neighbor by right shoulder (2s move up). |

| 3-8 | 1W follows 1M who goes left shoulder round the 3s (going on the outside of 3W) to face 2M, with 1W still following her partner | |

| B1, B2 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, 4 half-dolphin heys on the diagonals, starting by passing 2M right shoulder, then (with 1W in the lead) passing 3M right shoulder, then passing 2M (in 3W’s place) by right shoulder, then 3M (in 3W’s place), ending with the 1s in 2nd place, proper, facing the men’s side, moving into a . . . | |

| C | 1-4 | 1s and 2s right hands across once around |

| 5-8 | 1s and 3s left hands across halfway, then partners turn by the left halfway |

Trevor notes that he originally wrote this dance as a triple minor longways with a triple progression, but now prefers it as a three-couple dance. The alternative end for the triple minor, triple progression version is:

| C | 1-4 | 1s and 3s left hands across halfway, then partners turn by the left halfway |

| 5-8 | 1s with the 2s below them, right hands across halfway, then partners turn by the right halfway |

The Flight of the Falcon

Barry Priddey

Anniversary Tensome, 1992

Scottish country dance

Longways for 4 couples; 3 couples active

Tune: 32 bar jigs, 8 times through

Mini-crib

| A1 | 1-4 | 1s set and cast to second places, 2s moving up on bars 3 and 4 |

| 5-8 | 1s turn by the left 1¼ to end with 1M facing his first corner (3W) with 1W standing behind him | |

| A2 | 1-8 | With 1s dancing as a unit, dance a full dolphin reel of 3 with 1st corners (3W and 2M) |

| B1 | 1-8 | 1M, followed by his partner, face his second corner (2W) and dance a full dolphin reel with 2W and 3M; 1s end each facing their first corner (1W face 2M and 1M face 3W) |

| B2 | 1-4 | 1s turn 1st corners by the right, then pass each other by the right shoulder to face second corners |

| 5-8 | 1s turn 2nd corners by the right, then pass each other by the right to end in second places, proper |

Golden Dolphins

Sue Carter, 2005

Published online

English country dance

Longways for 5 couples

Tune: Golden Dolphins, by Colin Hume

| A1 | 1-4 | All set; top and middle couple cast down one place, 2s and 4s leading up |

| 5-8 | Ends left-hands across while the new middles gypsy left | |

| A2 | 1-4 | All set; bottom and middle couple cast up one place, the couples above them leading down |

| 5-8 | Ends right-hands across while the new middles gypsy right. (End 2 – 4 – 1 – 5 – 3) | |

| B1 | 1-4 | Partners two hand turn, ending with the top three couples facing up, bottom two facing down for a |

| 5-16 | “Morris Dolphin Hey” – end four pairs (working with same-sex neighbor) changing the lead each time they start moving in, middle couple “swim alone” * | |

| B2 | 1-12 | Middle couple cross right, turn right, dance a quick whole figure eight round the entire set while the end couples do four changes of a circular hey starting with partner (4 steps per change), then two-hand turn while middles finish their figure eight. |

| 13-16 | Lines fall back; lead forward. |

* In an ordinary morris hey for 3 dancers, both top and bottom dancers cast out while 2 follows 1 up and out. 1 passes 3 by the right, then 3 passes 2 by the left, then 2 passes 1 by the right, etc.

In this “morris dolphin hey,” the paired units (dolphins) are on the sides of the dance. Colin Hume writes that: ” . . . the same-sex dancers, for example 2M and 4M, act as one and they keep the same relationship to each other throughout: 2M is always above 4M. Their cast is an individual turn out of the set so that 4M actually takes the lead at the start. Men 4 and 2 pass left shoulder with man 1 and then right shoulder with men 5 and 3, so essentially there are two heys for three up and down the set.”

Colin adds that for the whole figure eight in B2, “the middle couple cross right and the man goes round the bottom four dancers while the woman goes round the top four dancers, then they cross left and turn left to go round the other four dancers, finishing where they started.”

Halsway Manners

Mary Devlin, 1999

Published online

English country dance

Longways for 3 couples

Tune: Halsway Manor Jig, by Liz Donaldson

| A | 1-4 | Lines of three dance forward a double and fall back |

| 5-8 | End couples back to back while middles right shoulder gypsy once & a bit more (end with 2W ready to head up the set toward 1M, followed closely by her partner) |

|

| B1 | 1-8 | With the 2s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey for three on the men’s side of the set (2W pass right shoulder with 1M to begin); end with 2s heading up the set toward the 1W to . . . |

| B2 | 1-8 | With the 2s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey for three on the women’s side (2W pass left shoulder with 1W to begin); end with 2s heading up the set proper toward the top couple to . . . |

| C | 1-4 | 2s split the 1s with a handy hand turn 1½ sending the 1s dancing down the set to . . . |

| 5-8 | 1s split bottom couple with a handy hand turn 1½ (to change places); polite turn at the end of the line. |

End in 2-3-1 order.

[Eds: skip-change of step recommended for the two heys. Also note that the name of the Manor is pronounced “hall-sey” not “hall-sway.”]Jack’s Dolphin

Chris Turner, 1999

Ramblings of a London Gentleman

English country dance

Square set

Tune: Jack’s Maggot

| A1 | 1-8 | With the heads dancing as a unit and the women in the lead, heads dolphin hey with the nearer side couple (1W passes left shoulder with 2M to begin; 3W passes left with 4M). All end at home. | |||||||||

| A2 | 1-8 | With the sides dancing as a unit and the women in the lead, Side women lead a dolphin hey with the nearer head couple. All end at home. | |||||||||

| B1 | 1-2 | Heads dance half a RH star (4) while sides dance half a RH turn | |||||||||

| 3-6 | A full left-hand star on the sides (heads are not in the same star as their partner) | ||||||||||

| 7-8 | Heads dance another half a RH star while sides dance another half a RH turn to get back home | ||||||||||

| B2 | 1-6 | Men promenade three places CCW to progress while women circle left all the way | |||||||||

| 2-8 | All turn new partner two hands | ||||||||||

|

Just Skylarking

Rhodri Davies, 2007

Directions online

Duple improper contra

| A1 | 1-4 | Balance the Circle (join hands four and balance in and out) (2); Petronella turn (2) |

| 5-8 | That again | |

| A2 | 1-8 | Neighbors balance and swing, ending facing down in a line of 4 |

| B1 | 1-8 | Lines of four down the hall, Dixie Twirl*; Lines of four up the hall end in a line facing 2W, with 1s in the center (4) |

| B2 | 1-8 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey with 1M passing 2W by the right shoulder to begin. End with 1s looking down the hall for a new couple, 2s looking up the hall |

* Dixie Twirl: Never let go! Facing down, 1s (in the middle) make an arch, 2W goes under while 2M leading 1W moves to his right so that 1W turns the arch over her partner.

Rhodri writes: “I have run across a variation from Geoff Cubitt that I am quite happy with. It gives you a swing with your partner as well as your neighbor. The B parts are the same.”

| A1 | 1-4 | Petronella twirl to the right |

| 5-8 | Swing partner on the side, face across | |

| A2 | 1-4 | Petronella twirl to the right |

| 5-8 | Swing neighbor, end facing down |

Kinematic Dolphin Vorticity

Luke Donforth, 2016

Published online

Duple improper contra

| A1 | 1-4 | In long lines, forward and back (4) |

| 5-8 | 2s hand cast (“gates”) the 1s down through the middle to a line of 4 (4), ending in a line with 1s in the center, facing 2W | |

| A2 | 1-4 | With 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey for 3, 1M passing 2W by the left to begin |

| B | 1-8 | Partners gypsy and swing |

| B2 | 1-4 | Circle left 3/4 |

| 5-8 | Neighbors swing |

Movement Afoot

Alan Winston, 2013

Longways duple minor

Tune: Steciak’s, by Larry Unger

| A1 | 1-2 | Men set forward to women (bourée-ish stamping optional*) |

| 3-4 | Men fall back as women come forward | |

| 5-6 | All turn single right (women end at home place) | |

| 7-8 | Partners turn right halfway | |

| A2 | 1-8 | As above, with women leading. Keep right hands joined at the end, and . . . |

| B1 | 1-4 | . . . take left hands as well for half-poussette CW to progressed places |

| 5-8 | A double Mad Robin** with 1W and 2M passing through the middle first | |

| B2 | 1-8 | 1s acting as a unit, dolphin hey for three: 1M turns around coming out of the Mad Robin to start passing left shoulder with 2M; all finish progressed and proper. |

*Alan writes: “I want the A1-A2 to have the people who aren’t going forward to hold their ground while their partners get right up in their faces.”

[**Eds: Partners face. Moving on an oval track and always remaining facing, 1s dance down and then up while 2s dance up and then down. On the first half, 1W and 2M pass through the middle; on the second half, 2W and 1M pass through the middle.]Opo

Barry Skelton

Published in The Dolphin Book; 11 Scottish Country Dances, 1994

Scottish country dance

Longways for 4C, 3C active

Tune: 32 bar reels X 8 (Barry suggested Isle of Sky; that tune is also known as George Brabazon [II], attributed to O’Carolan.)

Mini-crib

| A1 | 1-4 | 1s cross giving right hand and go below, 2s moving up on bars 3 and 4 |

| 5-6 | Joining inner hands, 1s dance up to between 2s | |

| 7-8 | 1s turn by the right to end with 1W facing 2M and 1M facing 2W | |

| A2 | 1-8 | 1s and 2s dance a right-shoulder reel of four across the set. 1W ends by facing 2M while 1M, turning around by the left, ends behind 1W |

| B1 | 1-8 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin reel of 3 with the 2s, 1W passing 2M by the right to begin |

| B2 | 1-4 | 1s dance down between 3s, cross over at the bottom, and cast up around them to second places, improper |

| 5-6 | 1s cross giving right hand | |

| 7-8 | Joining hands on the sides, 2s, 1s and 3s set |

Orca

Barry Skelton The Dolphin Book; 11 Scottish Country Dances, 1994

Scottish country dance

Longways for 4 couples, 3 couples active

Tune: 24 bar reels, 8 times (Barry suggested Teviot Bridge)

Mini-crib

| A | 1-4 | 1s turn by the right hand and cast down one place, 2s moving up on bars 3 and 4 |

| 5-8 | 1s dance down between 3s and cast up to middle place, facing up | |

| B1 | 9-16 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey across the set with the 2s (1W passing right shoulder with the 2W to begin) |

| B2 | 17-24 | 1s dance up between 2s, cast to 2nd place and turn by the right hand |

Orca

Barry Skelton, adapted by Ron Coxall

Walls, 2005

English country dance

Longways duple minor

32 bar reels

| A1 | 1-4 | 1s cast down to second place, 2s moving up, |

| 5-8 | 1s lead through the next 2s below, cast up to finish between their own 2s and face to the right | |

| A2 | 1-8 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin reel of 3 across the set (1W passes right shoulder with 2W to begin), ending facing up and holding hands in a line of four, 1s in the center |

| B1 | 1-4 | Lines up a double, fall back, closing into a circle of four |

| 5-8 | Circle left | |

| B2 | 1-8 | Double figure eight: 1s crossing up to start while 2s cast down. |

Pelorus Jack

Barry Skelton, 1993

Published in The Dolphin Book; 11 Scottish Country Dances, 1994

Re-published in RSCDS Book 41, 2000

Scottish country dance

Longways for 4 couples, 3 couples active

Tune: 32 bar jigs, 8 times (Barry suggested The Peterhead Express)

Mini-Crib

| A1 | 1-4 | 1s cross giving right hands and dance down one place, 2s moving up on bars 3 and 4 |

| 5-8 | 1s and 3s right hands across, ending with 1M facing his first corner (3W) with his partner behind him | |

| A2, B1 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, four diagonal half-dolphin heys, starting with 1M’s 1st corner, then 1M’s 2nd corner, then 1W’s 1st corner position, then 1W’s 2nd corner position | |

| B2 | 1-4 | 1s and 2s left hands across |

| 5-6 | 1s left-hand turn halfway | |

| 7-8 | 2s, 1s, and 3s join hands on the side and set |

The Potter’s Wheel

Chris Sackett and Brooke Friendly, 2009

Impropriety III

English country dance

Longways duple minor

Tune: The Snowy Path, by Mark Kelly

9/8 meter

| A | 1-4 | Four changes of rights and lefts (right hand to partner to begin) |

| 5-8 | Ones right-hand turn 1½ to end facing 2W (1M in the lead) | |

| B | 1-4 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey for 3 across the set with 1M passing left shoulder with 2W to begin |

| 5-6 | 2s follow the curve of the hey to make big cast up to 1st place while 1s, with 1M in the lead, dance down the middle of set and curve to own side in 2nd place | |

| 7-8 | Partners right-hand turn once round |

Sapphire Sea

Christine Robb, 2015

Published online

English country dance

Longways duple minor

Tune: Tom Kruskal’s, by Amelia Mason & Emily Troll

| A | 1-4 | Circle 4 once around |

| 5-8 | 1st corners right-hand turn once around | |

| 9-12 | 2nd corners left-hand turn once around | |

| 13-16 | 1s cast down into the middle of a line of four while 2s lead up and cast to the ends of the line. (All face 2W: 2W – 1W – 1M – 2M) | |

| B | 1-8 | With the 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey across the set with the 2s (1W passes right shoulders with 2W to begin). End in a line of four facing up. |

| 9-12 | Line leads up a double and falls back | |

| 13-16 | 2s gate the 1s up and around, letting go early to drift into new circles |

Somerset Square

Philippe Callens, 2009

Seasons of Invention, 2011

English country dance

Square set

Tune: A Trip to the Bar, by John Hymas

Part I

| Al | 1-2 | Head couples lead in. |

| 3-4 | Head couples fall back, while side couples lead in. | |

| 5-6 | All cloverleaf turn single (men left, women right), heads in place, sides moving back to places. | |

| A2 | 1-2 | Side couples lead in. |

| 3-4 | Side couples fall back, while head couples lead in. | |

| 5-6 | All cloverleaf turn single (men left, women right), sides in place, heads moving back to place, head women moving to finish in front of their partners facing in | |

| B | 1-4 | Head couples right shoulder dolphin gypsy three-quarters * to finish in the center of the set, facing each other across the hall, women on the men’s right. |

| 5-6 | Heads, taking nearer hands with partner, set. | |

| 7-8 | Heads cross the set passing right shoulder and face the sides. | |

| 9-10 | In fours, left hands across halfway | |

| 11-12 | Letting go of hands, head women followed by partner move CCW single file into original place where they turn left to face partner, while sides left-hand turn halfway into original place. | |

| 13-16 | Partners set and turn single. |

Part II

Repeat Part I, with the sides starting the movement in A1 and B

Part III

| Al | 1-4 | All lead in, change hands and lead out. |

| 5-6 | All cloverleaf turn single, men right, women; end facing out. | |

| A2 | 1-4 | Corners lead out on the diagonal, change hands and lead in. |

| 5-6 | All cloverleaf turn single, men right, women left, finishing facing in. | |

| B | 1-4 | Women move clockwise halfway around the set, first in front of partner, then behind the next man into opposite woman’s place (skip change step). |

| 5-8 | Men move counter-clockwise halfway around the set, first in front of opposite (now on their right) then behind the next woman into opposite man’s place (skip change step) | |

| 9-12 | Partners two-hand turn finishing in a double star facing around counterclockwise, men on the inside, partners nearer hands joined. | |

| 13-16 | Double star halfway around (skip change step). Finishing in star formation partners face and honor. |

*In a dolphin gypsy two couples dance clockwise around each other, each couple acting as a unit. The movement is begun by the women leading and the men following. Having moved halfway around, the men take the lead and the women follow. Partners should have their shoulders parallel to each other throughout this movement.

Under the Influence

Jenna Simpson 2013

Under the Influence, 2017

English country dance

Longways for 4 couples, 1s & 3s improper

Tune: Tom Kruskal’s, by Amelia Mason and Emily Troll

| A1 | 1-4 | In circles of 4 at the ends, all balance and Petronella turn one place to the right. | ||||||

| 5-8 | In longways set of 8, all balance and Petronella turn one place to the right to end | |||||||

|

||||||||

| A2 | 1-4 | In longways set of 8, all balance and 2-hand turn partner once round | ||||||

| 5-8 | Circle 8 left halfway to end | |||||||

|

||||||||

| B1 | 1-8 | Using a skip-change step and with nearer hands joined, the 1s (in the center on the ladies’ side), dancing as a unit with 1M in the lead, initiate a right-shoulder dolphin hey across the set with the couple at the bottom; meanwhile the 4s do likewise with the couple at the top. Then, changing the lead and changing hands, the 1s and 4s pass each other in the middle by the right to switch ends into the second half of the heys across the set. Then, changing the lead and changing hands again, the 1s and 4s dance, respectively, into 2nd place proper and 3rd place improper and face out the ends. | ||||||

| B2 | 1-4 | In groups of 4 at the ends, dance a mirror back to back, middles (1s and 4s) splitting the ends to begin. | ||||||

| 5-8 | At the ends, circle 4 to the left once round. |

Jenna notes that the figure in B1 is a variation on the dolphin hey/reel. “In this dance, the handhold requires the tandem couple to be offset rather than one behind the other, and as the lead is changed, hands are necessarily changed as well. Also, in this dance the tandem couple only dances half a hey at each end (while the end couples dance full heys across the set). Ultimately, the handhold is an embellishment; groups just learning the figure may find it easier to dance without hands.”

Waves of Grain

Bob Green, 2012

CDSS News, Fall 2015

Longways, duple improper: starts in long wavy lines, men facing out

Tune: Wheat, by Martha Edwards

3/4 meter

| Al | 1-2 | Set down the hall, set up the hall, |

| 3-4 | All take two chassé steps down the hall | |

| 5-6 | Set up the hall, down the hall, | |

| 7-8 | All take two chassé steps up the hall | |

| A2 | 1-4 | Neighbors turn right once and a half |

| 5-8 | Partners back-to-back | |

| Bl | 1-8 | With 1s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey across the set with the 2s (1W passing left shoulder with 2M to begin) |

| B2 | 1-8 | With 2s dancing as a unit, dolphin hey with the 1s (2W passing left shoulder with 1M to begin) |

Windhover

Robert Sibthorpe, 2004

Published online in Inscape

English country dance

Longways for 5 couples: Active couples are 1s & 3s

Tune: Windhover by D. Pattenden, 2004

| A1 | Active couples cross, giving right hands, and cast to the foot of the set, then dance up the center of the set, in order: 3W, 3M, 1W, 1M. Meanwhile, 2s and 4s move up. End with 3s facing 2W and 1s facing 4W: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B1 | With couples 1 and 3 each dancing as a unit, parallel dolphin reels on the diagonal, 3W passing right shoulder with 2W and 1W the same with 4W; 2M and 5W stand still | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| B2 | The dolphin couples veer to the left to dance parallel dolphin reels on the other diagonal, 3W and 2M passing left shoulders to begin as do 1W and 4M. End with the actives in the center, 3W and 1W turning to face partner in a line up and down the set for . . . | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A2 | . . . a half-reel of 4 along the center of the set, end facing out at ends; 1s at the top cast (M left, W right) to 3rd place while 3s cast (M left, W right) up to 4th place and cross down to bottom place |

Appendix 3: The Migration Routes of the Dolphin Hey

|

The Migration Routes of the Dolphin Hey |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

“Halsway Manners” US path |

Scottish country path |

Via England |

|

|

Pre-1900 |

Shetland Reel – traditional dance |

||

|

1947 |

Pat Shaw visits Shetlands, collects dances |

||

|

1977 |

John Drewry: The St. Nicholas Boat with a Shetland Reel |

Pat Shaw: The American Husband with Shetland Reel |

|

|

1981 |

Drewry: Ferla Mor (Shetland Reel for one tandem couple) |

||

|

1992 |

Barry Priddey (UK): The Flight of the Falcon |

||

|

1993 |

Barry Priddey: The Capercaillie |

||

|

1994 |

The Dolphin Book is published. |

||

|

1995 |

Elma See introduces dolphins in Ottawa, Bruce Hamilton (US) learns the figure |

||

|

1996 |

Brooke Friendly & Chris Sackett (US) learn Dancing Dolphins |

Ron Coxall (UK) learns figure in Australia, teaches it at Eastbourne Festival to Sue Carter, Trevor Monson, et al. |

|

|