by Mark Matthews

Mark Matthews writes and calls for dances in western Montana. This paper was gleaned from his book Cakewalking out of Slavery: A Study of Racism through Music and Dance, 1619-1910). It is part of the four-volume series called “Swinging through American History.” Other volumes include: Square Your Sets: The Birth of American Social Dance, (1651-1935); Promenading toward Democracy: The Great Square Dance Revival, (1935-2010); and Jitterbugging across the Colorline: Desegregating the Dance Floor, (1910-1980). For more information about these books, contact Mark.

For both black and white Americans, the dance known as the cakewalk—which reached a zenith in popularity from the 1870s to the turn-of-the-century—served as a cultural bridge from plantation/frontier society to the modern industrial age. It was the first African-American dance to achieve national exposure and to saturate white culture both onstage and in the parlor. The dance marked the commencement of the transformation of slave art into modern black American culture. It also paved the way for the acceptance of African-American dance and music in the United States—as well as around the world. The cakewalk was the first step, so to speak, that ultimately led to African traditions dominating American pop culture—which in turn helped to racially integrate this country.

By the 1890s, the manner in which people lived in both Europe and North America was radically changing and so was popular culture. “A society which was more and more ceasing to be society in the old sense could not be fed on stale, warmed-over delicacies from the princely kitchen,” observed Curt Sachs in 1937. Whites on the two continents were switching from merely admiring black dance, Sachs said, to adopting “with disquieting rapidity” (as he put it) a succession of slave dances. [Sachs, Curt. World History of the Dance. New York: W.W. Norton (1937), 444-5.]

The origins of the cakewalk are lost in history, but two apocryphal theories surfaced at the turn of the nineteenth century—with both focusing upon the matrimonial sacrament. One report theorized that the cakewalk started with the French blacks of Louisiana around 1700. Apparently, male slaves in New Orleans at that time entered a cakewalk to claim a mate. “In effect the cake walk was not different from the old Scotch marriage watch which required only public acknowledgment from the contracting parties,” reported a newspaper. The dance itself allegedly resembled several old French country dances. [The Washington Post, “Cake-Walk Strikes London, The.” 4 Apr. 1898: 6.]

Also in 1898, a black entertainer in New York City claimed to have heard a tale from an ex-slave that placed the origin of the cakewalk in early colonial Virginia, where a wealthy planter allegedly ordered a competition between two male house slaves who were wooing the same female slave. “Accordingly [the master] gave all hands a holiday, invited his friends as spectators, and prepared for a grand walking match for the hand of the dusky bride. In order to heighten the rivalry he ordered the cook to prepare a monster cake, which should be carried off as a trophy and foundation for the bridal feast of the successful competitor.” [The Washington Post, “Chat About Stage Folk.” 6 Feb 1898: 22.]

Around 1915, Ethel Urlin proposed this intriguing theory: “negroes borrowed the idea of it from the War Dances of the Seminoles, an almost extinct Indian tribe. The negroes were present as spectators at these dances, which consisted of wild and hilarious jumping and gyrating, alternating with slow processions in which the dancers walked solemnly in couples. The idea grew, and the style in walking came to be practiced among the negroes as an art.” However, Urlin offered no sources to support her theory. [Urlin, Ethel L. Dancing, Ancient and Modern. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent (circa 1915). Web. Open Library. Internet Archive. 29 May 2014: 13.]

With no substantiation, the above three theories cannot be taken too seriously. More modern historians believed that the slaves borrowed the structure of the cakewalk from the grand march—or promenade—with which white couples kicked off a ball by entering the hall in file with pomp and circumstance. In turn, the grand march likely evolved from the procession of the twelfth century, during which couples, or trios, walked in formation through a town or village to the accompaniment of strolling musicians. When royalty took part in a procession, Rules of Precedency evolved that determined the order in which the couples would line up—with the king and queen at the head, of course. By the mid-1800s, the elite class in the United States typically opened their balls with a grand march.

The idea of presenting a cake or other edible prize for a dancing or athletic match also had precedence. Aubanus, a writer of the sixteenth century, noted that “at the Easter season there were foot-courses in the meadows in which the victors carried off each a cake. . . .” A Puritan writer of the same era warned: “All games where there is any hazard of loss are strictly forbidden; not so much as a game of stool-ball for a tansy [herbal plant].” And in 1657, a poet alluded to cake, sugar, wine and a tansy as prizes for winning a round at “stool-ball.” [“Our One Hundred Questions.” Lippincott’s (Jan 1889): 137.] Moreover, as Jamison pointed out, winners of dance contests during the late seventeenth century in County Westmeath, Ireland, often won “cake and apples” for their efforts. [Jamison, Phil. Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Southern Appalachian Dance. Urbana, Ill.: U. Illinois P. (2015):123.]

During their version of this pageantry, slaves assumed the classic European dance carriage by keeping their torsos erect, lifting their feet from the ground (not shuffling) and moving vertically. However, of even more significance, they added an African flair by injecting a swing into their movements. Dressed in secondhand finery they performed a high-kicking, prancing and strutting walk-around to a musical accompaniment that gained more swing in rhythm as the decades passed.

During slavery times, to prepare for a walk at a Southern plantation blacks first cleared and swept the lawn in the center of their cabins or some other open area, and then marked out a circular track. Oftentimes, in the center of the loop a cake stood on a stand which might be “profusely decorated with greens and festoons of colored tissue-paper.” A white observer described one trophy cake as resembling “a cart-wheel in its dimensions.” The walkers often drew lots for partners. The judges could include either the plantation owner and his guests, or distinguished individuals from the slave community. A variety of instruments—depending on the availability of local musicians—provided the music. Often, the slaves’ own voices accompanied the musicians. Once the walk commenced, the participants pranced around the track until the judges “were weary” and signaled for a halt. The umpires then presented the cake to the winners, “who were then publicly acknowledged, by reason of their superior grace and taste, to have won or taken the cake.” [“Our One Hundred Questions.” Lippincott’s (Jan 1889).]

In some regions slaves participated in a cakewalk that followed a straight line marked by chalk. This likely occurred in confined indoor spaces. “There was no prancing, just a straight walk on a path made by turns and so forth, along which the dancers made their way with a pail of water on their heads. The couple that was the most erect and spilled the least or no water at all was the winner,” according to Lynn Fauley Emery. Slaves referred to this type of performance as the “chalk line walk.” [“Our One Hundred Questions.” Lippincott’s (Jan 1889): 92.]

Slaves in early cakewalks occasionally caricatured idiosyncrasies of movement and behavior of certain whites who they may have known. One former slave explained: “Us slaves watched white folks’ parties where the guests danced a minuet and then paraded in a grand march . . . Then we’d do it, too, but we used to mock ’em, every step. Sometimes the white folks noticed it, but they seemed to like it. I guess they thought we couldn’t dance any better.” [Stearns, Marshall and Jean. Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. New York: Da Capo (1994): 22.] Consequently, slaves used the performance as a means to vent frustrations resulting from physical and psychological suppression—as well as to simply have fun. Whereas whites stereotyped blacks with the Jim Crow dance, blacks turned the tables when they mocked their white oppressors during the cakewalk.

Servants who worked in intimate contact with whites in the “big house” and who developed more refined manners themselves, likely introduced the cakewalk to the field hands. Consequently, participants in the dance avoided hip gyrations, torso twistings, slouched carriages, jig steps, and the general “wildness” of a typical slave dance. Years after the Civil War, a cakewalker explained: “Fancy steps don’t go with us. We have to walk straight, and the most dignified of the steps are the ones that catches the cake. They judges us by the collar and the pants and the most gracefulness in keeping time to the music.” [The Washington Post, “Here and There.” 2 Mar 1896: 3.]

Fancy steps may have been frowned upon, but individuals often developed their own “little tricks of grace.” For the women these might include subtle movements such as “turning [the] toes a trifle out and then giving them a sudden turn in”; or, lifting one foot, “like a young pullet about to steal upon a forbidden flower-bed where the seed has been newly sown,” and then following it cautiously with the other. Sometimes a female dancer “minced, like an old maid that is afraid of not being graceful” only to switch into a “long, swinging step that was the perfection of grace itself.” [Dromgoole, Will Allen. “Sweet ’Lasses.” Arena 17 1 (Dec. 1896-Jun. 1897: 151.] Another writer noted the fine points to be considered were “the bearing of the men, the precision with which they turned the corners, the grace of the women, and the ease with which they swung around the pivots.” [Johnson, James Weldon. The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. (1912). Electronic text—no page numbers. Project Gutenberg. Web. 1 Apr 2015.]

Over time different cakewalk styles developed that would lead to various categories of walkers, including “straight,” “fancy,” “burlesque,” and “rag-time.” One writer also described cakewalkers who had “a jumping step in time to the music,” but did not identify their specific category. However, by the turn of the nineteenth century, the style had apparently changed drastically. Eventually, “fancy and original movements” most influenced the judges when picking the winners. [New York Times, “Harvard Can Play Football.” 8 May 1895: 6.] “Legs were kicked higher, steps became faster and more intricate and spectacular leaps and turns were introduced,” reported Todd Arthur in Dance magazine.

Black minstrel shows first spread the cakewalk culture about the country when they performed a “walk around” in front of audiences composed of whites and black freedmen. [Sherlock, Charles Reginald. “From Breakdown to Rag-time.” Cosmopolitan 31 6 (Oct. 1901): 631.] After the Civil War, the cakewalk took on a life of its own. The term itself eventually attained a generic quality, such as “hoedown,” and many people referred to a cakewalk as a gathering for a black frolic. In 1894 a reporter for the Louisville Commercial described a black dance party that featured an evening of quadrilles. At dawn the caller announced “the company assembled will walk for the cake and the two most graceful pedestrians will be awarded the pastry.” [The Washington Post, “Was a Swell Affair.” 5 Feb 1894: 7.]

Louisville claimed to be the birthing grounds of the commercial, or professional, cakewalk. One writer, when referring to the events, described the city as a place where enterprising theatrical managers catered “to the city’s appetite for the novel” (Peterson). References to the cakewalk as a commercial venture and public performance first appeared in the northern press in the early 1870s when the New York Times reprinted an article from the Pottsville Miner’s Journal in Pennsylvania that described a cakewalk that raised money for the local African Methodist Episcopal Church. The headline in the Times read: A Mystery Explained—with the “mystery” being the cakewalk itself. [New York Times, “Mystery Explained, A.” 13 Dec. 1874: 4.]

Over the years, the prize cake became a symbolic award as sponsors offered a variety of awards such as gold-headed canes, silver watches, silver cups, jewelry, and cash. An Atlantic City tavern came up with one of the more unique prizes: “First prize, one case of beer; second prize, one dozen beer; third prize, six bottles of beer; consolation prize, half-dozen of beer.” The winners were required to dispose of their winnings “before leaving the hall.” [New York Times, “Beer Prizes at a Cakewalk.” 12 Nov. 1897: 2.]

Short video of a cakewalk from 1903, from the Library of Congress.

By the late 1870s, Billy and Cordelia McClain, two black entertainers who had migrated north, introduced the cakewalk to Gotham City. “Mr. McClain and I led one on the stage in the South,” said Cordelia McClain. “Well, we were considered a very graceful couple, and were asked to give the walk in the North. We did, and thus started the regular cakewalk.” [New York Times, “Fun for the Darkies.” 2 Jun. 1895: 16.] At the beginning of the craze during the late 1870s, promoters in New York City sponsored extravagant affairs during the Christmas holiday season, at first affixing the cakewalk onto other established forms of entertainment—such as the Great London Circus that appeared at New York’s Hippodrome on December 23, 1877. That evening, the master-of-ceremonies announced that the judges would look for “the greatest elasticity of limb, combined with the greatest ease of motion” from the ten couples. [New York Times, “Walking for the Cake.” 23 Dec. 1877: 2.]

Unlike their coverage of white cultural events, reporters at cakewalks often described in detail many of the personal physical attributes of the participants—especially the shade of their skin color. The journalist at the Hippodrome that evening reported the couples as “all rather brown as to complexion.” In later articles, other writers would provide even more nuanced descriptions, such as “light colored,” “very black,” “four shades lighter,” “yellow,” “peachblow,” “saffron hued,” “kinky headed,” “wooly head,” “brunnettish, but not decided enough for a type,” “a light mulatto couple with scarcely more than a healthily sunburned complexion,” “as black as the silk in which she was clad, both partners matching well in complexion,” and “a charcoal Chesterfield”—the last likely being a reference to Lord Chesterfield who, in the eighteenth century, wrote letters to his son propounding the manners and styles of proper society. No whites were allowed to compete in the competitions.

All reporters, just as they did when covering elegant white social events, also described in detail the style of clothing worn by the “fashion plates on parade.” At the event at the Hippodrome, a reporter described the dress of Miss Gray as: “white satin, with flowers festooned around the skirt. The trail was anywhere from a yard and a half to . . . two yards and a half long, and a large bouquet of white roses ornamented the space between the shoulders, on the front of the dress. Spotless white kids concealed the fairy fingers, and in the left hand was another large bouquet.” [New York Times, “Walking for the Cake.” 23 Dec. 1877: 2.] The men, many of whom worked as waiters, also dressed formally. Their attire frequently consisted of “swallow tail, white necktie, and snowy shirt front.” [New York Times, “Miscellaneous City News.” 30 Dec. 1877: 7.]

In 1878, the walks occurred more frequently at more venues. With the intensifying competition the walkers started to improvise in order to distinguish themselves. One couple “made an innovation by uncoupling their arms, and walking separately,” a Times reporter said. “By this means the grace and freedom of their carriage were much increased.” [New York Times, “Miscellaneous City News.” 30 Dec. 1877: 7.] Another couple “brought down the house by their backward walking . . . .” [New York Times, “Walking for the Cake.” 23 Dec. 1877: 2.] Sixteen years later, so many cakewalks had been reported in newspapers and magazines that one commentator suggested that they had “been described so often that a description of this one would not be of especial interest.” [The Washington Post, “Was a Swell Affair.” 5 Feb 1894: 7.]

A fair number of blacks apparently became professional cakewalkers. In 1886, Moses Green and Miss Heron were declared “the champion cakewalkers of New-Jersey.” By February that year, Miss Martha Garrison of New York had already won three cakes. New York writers dubbed Ben Butler “one of the most redoubtable cakewalkers in the city.” [New York Times, “Intruding at a Cakewalk.” 26 Feb. 1886: 2.] Dandy Jim was “the champion of Boston and Baltimore,” [New York Times, “Theatrical Gossip.” 26 Apr. 1892: 8.] while Luke Blackburn earned the title of “the present world’s champion.” [New York Times, “‘Polo Jim’s’ Cakewalk.” 15 Oct. 1893: 16.] However, he had some competition from Professor Snow, who was known as “the champion cakewalker of every continent.” [New York Times, “City and Suburban News.” 15 Mar. 1891: 3.] In 1896, promoters staged a cakewalk at the Odd Fellows’ Hall in Washington D.C. in order to determine once and for all “who is the best colored cake-walker.” The nominees included Charley Hodge, Howard Skelton, and Tommie Hawkins. [New York Times, “Raided a Camp of Hobos.” 5 Dec. 1896: 8.] Producers, who charged patrons at least twenty cents at the door, soon began paying couples “two dollars a night” or more to participate. [New York Times, “Miscellaneous City News.” 30 Dec. 1877: 7.]

The larger events often drew thousands of avid fans. The crowds not only included white laborers, office workers and merchants—but also members of the rich sporting crowd. Hecklers often insulted and jeered the performers. At one performance at the Hippodrome, after the stage manager had invited one couple back for an encore, “some laughter was mingled with the cheers, a few evil-minded persons believed the couple were called back to be laughed at.” [New York Times, “Miscellaneous City News.” 30 Dec. 1877: 7.] The volume of verbal abuse seemingly increased along with the popularity of the cakewalk—especially when the events moved into more intimate venues and attracted legions of white “butchers, bakers and produce men.” [New York Times, “Intruding at a Cakewalk.” 26 Feb. 1886: 2.] The aggressive harassment prompted a Times writer to berate the “proud Caucasian” who would “sneer at the institution of the cakewalk.” The writer compared the cakewalker not to an artist, but to “a work of art,” and felt dismayed that members of “a superior race” did not “cheer him on in this effort.” [New York Times, “The Cakewalk.” 18 Feb. 1892: 4.]

The commercialization of the cakewalk didn’t keep ordinary black citizens from participating in the jollity at their own gatherings. In 1896, The Washington Post noted that “every other week cakewalks are held in a hall on Sixth Street northwest, and many of the walkers can give the Primrose & West [Minstrel Show] people all the trumps and then beat them out.” [The Washington Post, “Here and There.” 2 Mar 1896: 3.] Blacks living in Culpeper, Virginia, often assembled to cakewalk at a resort called Cedar Hill Park just outside city limits. [The Washington Post, “Four Shot at Cakewalk.” 6 Sep. 1899: 4.] The cakewalk also joined fairs, festivals and “pound parties” as one of the main fund raisers for black churches. [New York Times, “Discord at a Cakewalk.” 18 Apr. 1896: 3.] One such event at Harlem’s Mount Horeb African Methodist Episcopal Church drew “as many white persons as colored ones,” including New York Governor Samuel H. Crook. [New York Times, “Walking for a Cake.” 23 Jul. 1886: 2.]

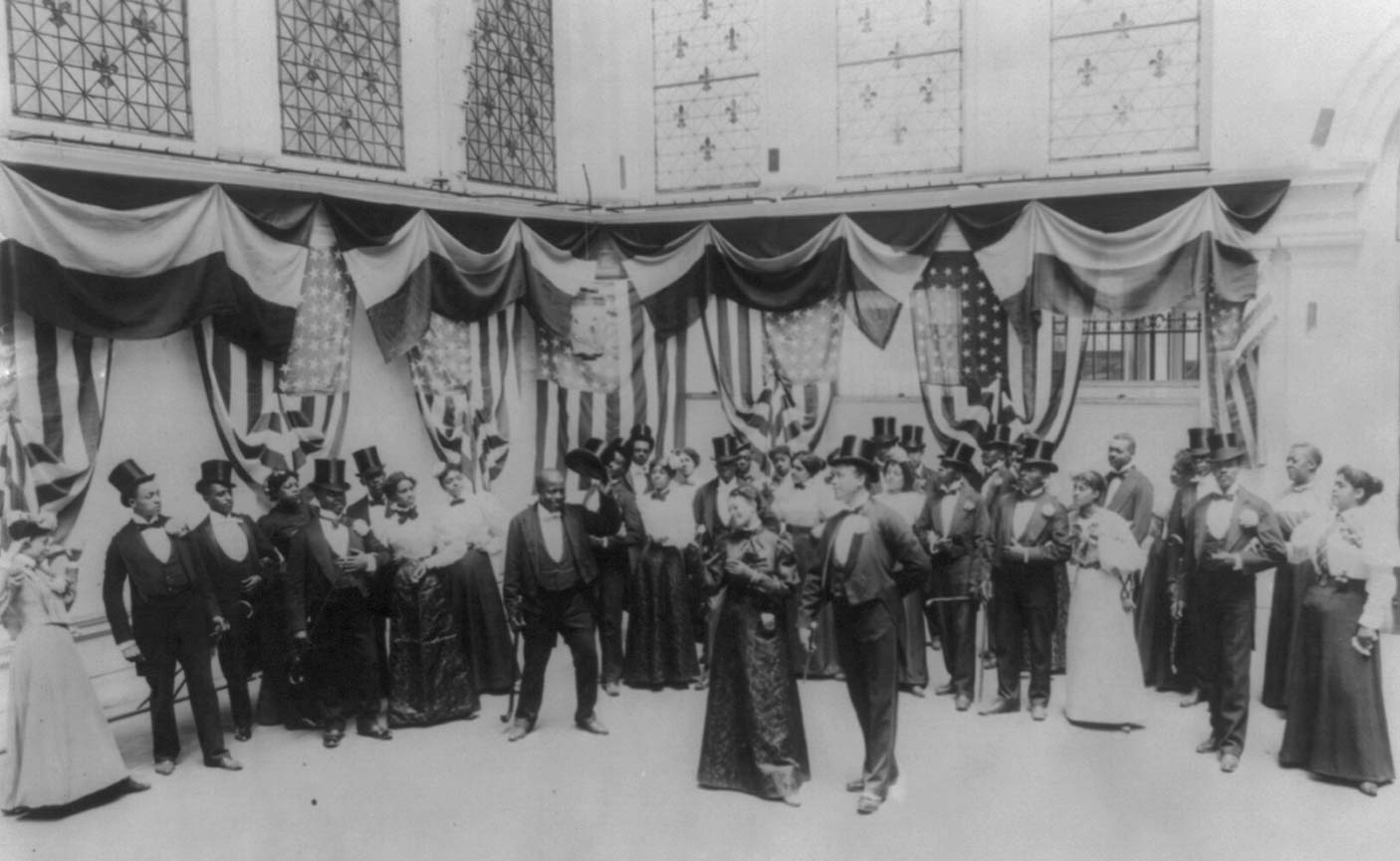

Private individuals also organized neighborhood cakewalks. At Fishkill Landing, a village on the Hudson River, local resident George Washington sponsored a cakewalk in honor of his good fortune when his wife gave birth to triplets. [New York Times, “George Washington’s Children.” 2 Jan. 1882: 2.] On April 16, 1898, Washington D.C.’s “colored 400” gathered at Columbia Riding Academy for their annual cakewalk. “Not a lady but was arrayed in an abundance of jewelry, and not a ‘gent’ but wore a sparkler in his immaculate shirt bosom,” said a newspaper report. [The Washington Post, “High Stepping for $25 Cake.” 16 Apr. 1898: 9.]

By the mid-1880s the term cakewalk had become part of American-English vernacular. Newspaper and magazine writers routinely utilized the expression “take the cake” to mean winning a prize; or for being the most outrageous or disappointing. Reporters of horse races by the end of the 1880s regularly used the term as a connotation for an easy victory, while boxing reporters picked up the term to describe a fight without much action. Not long after, political pundits started using “cakewalk” to express an easy victory by a politician or to denote a general election that included a number of candidates.

Some whites, especially university men and their female companions, applied burnt cork to their faces before attending local community cakewalks. Whites apparently enjoyed assuming a black persona in this way. In 1895, members of the Monte Relief Society presented a cakewalk and at Terrace Garden in New York where friends of the society “had hands and faces blackened, and were dressed in gorgeous raiment, befitting the characters that they assumed.” [New York Times, “Grand Cakewalk for Charity.” 29 Mar 1895: 3] In Washington D.C., where the Terpsichorean Club presented their annual masquerade ball in 1899, a group of “gaily attired negro imitators” participated in the “prize cakewalk.” [The Washington Post, “Danced for a Prize.” 17 Dec. 1899: 15.] Black face also penetrated the state of Maine, where the Cony High Minstrel Club of Augusta performed a cakewalk in 1899. [“County News.” Maine Farmer 68 7 (Dec. 1899): 4.]

When rich white families abandoned the cities for summer resort towns, many blacks followed in their wake to serve as waiters, porters and dishwashers. Frequently, the blacks staged cakewalks to entertain the white tourists. At Saratoga, New York, for instance, the waiters at the States Hotel presented their cakewalk at the town hall. The New York Times reported that “several parties of fashionables have been made up to look in upon it.” [New York Times, “Society at Saratoga.” 29 Aug. 1889: 4.] The same events also frequently occurred at the Hotel Shrewsbury at Seabright, New Jersey. [New York Times, “Doings at Seabright.” 25 Aug. 1889: 13.] By the end of the century, professional black minstrels also took their traveling shows directly to resorts such as Newport, R.I., where they presented the cakewalk as the pinnacle of an evening’s entertainment. [New York Times, “What is Doing in Society.” 17 Aug. 1899: 7.]

View a “Comedy” Cakewalk filmed in 1903, from the Library of Congress.

Over time, though, many resorts bypassed their African-American employees to invite their white guests to participate directly in the cakewalks. At Daggers’ Sulphur Springs outside Washington D.C., six white couples competed for the “large and tempting cake.” [The Washington Post, “Society Cakewalk at Daggers’ Springs.” 28 Aug. 1892: 13.] Meanwhile, at Bar Harbor, Maine, the Rockefeller crowd put on a “Deisarie” [sic: term unknown] cakewalk during which participants walked down a track as long as a football field and back. [New York Times, “Society at Bar Harbor.” 4 Sep. 1892: 4.] Not to be outdone, the Tatassit C.C. First Annual Regatta at Lake Quinsigamond in western Massachusetts held a cakewalk in 1892 during a clam bake. [“Tatassit C. C., First Annual Regatta.” Forest and Stream 39 13 (Sep. 29, 1892): 277.]

Cakewalks also routinely cropped up during the winter social season at private residences and public parties. At Kenwood, New York, Erastus Corning and his wife served oysters before a cakewalk at their home, for which they hired a black man as judge. [New York Times, “Gayety at the State Capital.” 10 Feb. 1895: 9.] In Baltimore, Mrs. John Moncure Robinson invited a “party of fashionables” to the Globe Brewery in a remote section of the city for some “bohemian” entertainment, which included a cakewalk. [New York Times, “Cakewalk for Baltimore Society, A.” 26 Nov. 1898: 2.] About four hundred guests attended a cakewalk presented by the Sherwoods of Glenbourne, Virginia, in honor of their son’s birthday. [The Washington Post, “Cakewalk at Glenbourne.” 31 Jul. 1899: 10.] Cakewalks became so common in high society that one Philadelphian pundit quipped that “New York’s Four Hundred have taken up the cakewalk as a refined and delightful social amusement, and the colored brother smiles with unalloyed gratification.” [The Washington Post, “Four Hundred in the Cakewalk, The.” 17 Jan. 1898: 6.]

By the 1890s, up to four thousand spectators routinely crowded into New York’s Madison Square Garden to watch “championship” cakewalks. The playbills for the evening’s entertainment also often featured opera singing, buck dancing, jig dancing, and skirt dancing. Chorales of jubilee singers, numbering one hundred voices by 1895, began the proceedings by delivering an hour of “plantation songs.” Smaller singing groups such as the Alabama Quartet, Morning Star (a double quartet), and Little Pickanniny Quartet also performed. Exotic acts included such performers as Mocking Bird Rube, the “Whistling Coon” and ten banjo players. These acts warmed up the crowd for the grand cakewalk which typically began at eleven o’clock sharp. [New York Times, “Missed a Man and Hit a Boy.” 17 Apr. 1892: 9.] [New York Times, “Wheelmen.” 2 Feb. 1895: 6.] Organizers promoted the first extravagant cakewalks held at the Garden as the The Grand Negro Jubilee. [New York Times, “Theatrical Gossip.” 26 Apr. 1892: 8.]

With its competitive nature, cheering crowds, referees, judges and athletic strutters, the cakewalk had always resembled a sports event. By the mid-1890s, the Ethiopian Amusement Company, which had ties to professional sports teams, promoted many cakewalk spectacles at Madison Square Garden. Pat Powers, who headed the enterprise, also presided over the Eastern Baseball League. Powers soon hired well-known boxing referees and baseball managers to “undertake the arduous and ungrateful task of picking a winning couple out of fifty at the big cakewalk in Madison Square,” the New York Times reported. [New York Times, “Cobwebs Beaten by Newburg Shooters.” 22 Feb. 1895: 6.] In addition, that newspaper began listing cakewalk competitions in its Calendar of Sports. Just like baseball teams, the New York cakewalkers traveled to competitions in many cities and states. [New York Times, “Challenge to a Cakewalk.” 13 Jan. 1898: 1.]

The cakewalk also infiltrated so many operettas and plays that Joseph Grant Ewing, in a satirical article for Puck, proposed to write a “unique” play for the stage in which “there will be no . . . cake-walks . . . ” [Ewing, Joseph Grant. “Modern Fairy Tales.” Puck 45 1149 (15 Mar. 1899): 11.]

The cakewalk stimulated so much curiosity among whites about black culture in general that they thronged to productions of black “spectacles.” In 1894, a full cast of “Ethiopian” entertainers appeared for the first time in a theater on Broadway when the Bijou Theatre staged The South before the War. The scenes were set on a cotton plantation, reported one critic, “and there is no drama to speak of, but, for people who like genuine darkey songs and dances and part singing, the performance will doubtless have some attractiveness.” The evening’s entertainment concluded with a prize cakewalk. [New York Times, “Colored Folks at the Bijou.” 20 Nov. 1894: 5.] The seeds for black theater during the Harlem Renaissance that would flourish from 1918 to the mid-1930s had been planted. The following year, black entertainers set up a living history spectacle called Black America at Ambrose Park in South Brooklyn that depicted life on a Southern plantation. The cast included five hundred people who lived in cabins on the premises. A cakewalk occurred every evening. [New York Times, “Fun for the Darkies.” 2 Jun. 1895: 16.]

The cakewalk also influenced European culture, both as stage entertainment and as a participatory dance. In January of 1898, the Pall Mall Gazette reported that “the interest excited by the novelty of the thing is giving place to an enthusiastic appreciation of the grace and charm of the performance.” [The Washington Post, “Cake-Walk Strikes London, The.” 4 Apr. 1898: 6.] In 1899, the Washington Post confirmed reports that the cakewalk was “tickling London mightily in farces, extravagances, and vaudeville.” [The Washington Post, “Theatrical Notes.” 8 Jan. 1899: 24.] And, in 1912, some Parisian critics referred to the dance as the “acme of poetic motion.” [Johnson, James Weldon. The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. (1912). Electronic text—no page numbers. Project Gutenberg. Web. 1 Apr 2015.]

Black invention was also heavily influencing popular musical tastes during the later part of the nineteenth century, when genres such as classic blues, jazz, boogie-woogie and urban blues first took root. However, two other musical genres fully blossomed at the turn of the century. The first, the “coon song,” was short-lived, but the other, ragtime, remained a musical force into the next century. By 1900, rag-time “professors” often warmed up the crowds at cakewalks by participating in piano contests. [New York Times, “Grand Central Palace Cakewalk.” 25 Jan. 1900: 10.] Individual singers also crooned ragtime at the competitive cakewalks, quartets harmonized it, and one hundred member-strong jubilee chorales shouted it. At Washington’s Convention Hall in 1900, six hundred spectators watched eighteen couples vie for the cake as the United States Marine Band struck up a rag-time selection. [The Washington Post, “Convention Hall Cakewalk.” 20 Feb. 1903: 8.]

However, by that time, the popular reign of the cakewalk was about to end. Only three years later, another cakewalk at Convention Hall drew only “a small crowd” that made the hall look “deserted.” [The Washington Post, “Convention Hall Cakewalk.” 20 Feb. 1903: 8.] However, by then blacks had moved on to a different form of dancing that was even more grounded in their own heritage—the one-steps, or zoo and barnyard dances, that included the grizzly bear, bunny hop, turkey trot and Texas tommy. And, there was much, much more to come.

The tide had turned. Whites were dancing like blacks. In time, they would share the dance floor with blacks. And finally, members of the two races would even dance together. Racial integration in America began to seem feasible.

The Cakewalk (with sound) from the late 1930s.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.

Thanks to the Massachusetts Cultural Council for their generous support.